At BoS USA 2014, Tony Ulwick, one of the fathers of the Jobs to be Done movement, looked at the tools and processes you can use to uncover innovation opportunities.

What are your customers trying to achieve, and how can you help them get there? Simple questions, but creating a disciplined approach to uncovering and capturing the answers is a huge step forward for your business. Watch the video for answers, for those who prefer, transcript is below.

Find out more about BoS

Get details about our next conference, subscribe to our newsletter, and watch more of the great BoS Talks you hear so much about.

Transcript

Tony Ulwick: Do you love that song? Thanks Mark. That song is evidence that Jobs-to-be-done Theory has gone mainstream, that’s what it’s all about. Excellent, well thank you, it’s a pleasure to be here. Thanks to everyone for getting up bright and early and making their way over, I appreciate that.

So obviously we’re all here to make a change in the world these days, right? Anyone here running a business, starting a business, creating products?

Yeah, I think we all are right? Perfect, perfect, so I’m in the right place, excellent. This is something we all share, we all want to create great products, and one of the first products I worked on was back in the 1980s, I worked for IBM for ten years, and I worked on a product called the PC Junior. Anyone familiar with that product? Yeah, I see it gets the respect it deserves. The day after that product was introduced, in the Wall Street Journal the headline reads, ‘PC Junior is a Flop’, and I thought, wow, that’s pretty impressive. We just came out with this product yesterday and they are already calling it a flop, and unfortunately they were right. That was the bad thing.

The very next day I’m thinking, how are they measuring the value of this product? Obviously they were measuring it some way we weren’t, and only if we did, only if we could figure out how they’re measuring the value of the product we could just create it in a way that would be more meaningful and be successful.

But that was a tough lesson, and the truth is that most of you will fall into the same situation at some point in your career.

It’s extraordinarily hard to create a new product, and most of you will go a lifetime without creating a successful product in the marketplace, which is truly unfortunate because we’re all here to make changes in the world and to create products that are really going to be game changers.

So we don’t want you to come to the same faults, right? Let’s think of a new way to innovate that you can avoid the 95% failure rates. I always found this interesting, you think of new product failure rates of about 95%, new business failure rates, 95%, the rate of new ventures failing, over 95%. It’s pretty consistent. It’s really hard to get things right. Especially if there’s no great process for helping you to get those things right and making sure you’re creating the right products.

So what I want to talk about is how can I help you, hopefully, create a better product and not succumb to this, and not be part of the PC Junior club, but be part of a club that’s far more successful.

So let’s talk about that.

We’re going to talk about innovation as a process.

and I love thinking about it a process, and I love thinking about it as an equation where you have solutions, and you have needs. What you’re trying to do is figure out what solutions, technologies, tools, techniques, can we combine and satisfy some way, some set of unmet needs.

Now, just like in any equation there’s constants and variables in the equation. We’re trying to figure out what’s the constant and what’s the variable, right? Well, obviously the solution is the variable that changes over time.

Now what that means is, there’s got to be a constant in the equation, so let’s think about how this typically works.

There’s a couple of ways to innovate, one is to come up with lots of ideas and see which one’s address customer’s unmet needs, and the other way is to uncover the customer’s unmet needs and then design a solution that specifically addresses them.

Of course, the most traditional approach to innovation does the former, it’s encouraged, lots of ideas, come up with ideas, brain storm. Go out of the box, open innovation, let’s get more ideas from external sources, you can’t have too many ideas. If you have lots of ideas, you’re inherently increasing your chances of one of them being good, so the theory goes.

So you take all those ideas, you filter those down to the ones you think are going to see the marketplace, you put them into development, and you begin to create them, you build them. You test them with customers; you bring them back out and ask them, ‘what do you think of this product’? ‘How can we make this better’? You go through this iterative process as you’re creating the product to help create a product you think is going to win in the marketplace.

Now this is interesting because all this leads to terms like pivoting, you get it wrong you can pivot and try to get it right, or maybe you can fail fast. But wouldn’t it be better yet to just get it right the first time?

This is really interesting because what we’re trying to do in the innovation process is to answer a lot of key questions like who am I trying to create value for, for example, and what problem am I trying to help them solve, and exactly what are their unmet needs, and which of those are unmet? Because again, we’re trying to come up with solutions that meet unmet needs. If we can’t do that successfully, our products aren’t going to see the marketplace.

In the traditional approach, many of these questions aren’t even answered when the product is launched, which is not good, and that’s why there’s just a 5% success rate. We want to flip this around so that it’s done entirely different. Innovation should be a needs first process where you come up with the customer’s needs and answer all these key questions up front. Who’s the customer? What problem are they trying to solve? What customer segment should we go after? Which unmet needs should be target?

Now, how many of you think you follow a needs-first approach in innovation versus an ideas-first approach? A show of hands. About half. How many of you that follow a needs-first approach would say that there’s agreement in your company as to what a customer’s need is? [Laughter]

We lost a lot of people there, apparently. Of those three or four that have agreement on what a customer’s need is, how many you would say that you have a complete set of customer needs, and you know all your customer’s needs? [Silence]

Okay, so there we go, all right. So, it’s interesting, maybe following needs-first approach, or trying to, but as you know it’s extraordinarily hard to do this, right? Why is this?

Customer’s needs are these elusive things that have not been well defined as part of an innovation process. Now you think about any process, any process has to have good inputs in order to get a great result. The innovation process is simply two things; I’m trying to come up with solutions that address unmet needs. If I don’t know what an unmet need is, and I can’t figure out which needs are unmet, and I can’t get my teams to agree which needs are unmet so we can agree on which solutions to work on, then it’s going to be extremely hard to be successful in the marketplace.

Let’s look at all these different statements, Delighters, Exciters, Must-haves, Solutions, and Specs. All these terms are used to describe customer needs statements. Now, do you think they’re all right? How many of you believe customers have latent needs, needs that they don’t even know they have?

I’m going to prove to you that that’s not true, they know their needs.

Beautiful, huh?

And so this is intriguing, this is one of the key elements of the whole process. We’ve been taught to think of innovation in such a way as a solution from a product-centric standpoint over the years that we believe these misconceptions about innovation to be true, like customers have latent needs, they can’t articulate their needs, and their needs change quickly over time.

I want to show you that none of those things are true, which is great news for you because since they’re not true there is actually a way to get at them and to execute the innovation process in a much more efficient manner.

It all begins with this, the jobs-to-be-done theory and the thinking.

This is really just the starting point. What Levitt did, I think, was open the door to a new way to think about the problem.

All of you are creating products, and you can focus on the product, the drill, but you can also focus on the underlying reason people are buying the product, which is the job. This is where Jobs-to-be-done theory starts. People buying products and services to get a job done, and if we can figure out what that job is, we can analyse that job and break in down step by step, and figure out how people measure success along each step of the way to get the job done, and then we can come up with solutions and see how well they addressed those metrics that people are using to measure success and getting the job done. That’s the essence of Jobs-to-be-done thinking, now making that work, of course, is quite difficult and that’s what we want to go through.

Everything that we’ll talk about is embodied in this process of called out from outcome driven innovation. We’ve been working on this for the past 22 years or so, and again, all this stems from the failures at IBM.

Again, think of the scenario, PC Junior’s a flop; people are using some metrics to make that determination. If we can figure out what those metrics are well in advance, we’ll just create our product around those metrics, and then the headline would be “PC Junior: Greatest thing since sliced bread’. So, how do we get there?

It’s all part of the journey.

We’re going to cover this in three different buckets, market definition, needs analysis, and strategy.

So let’s talk about markets first, and you’ll notice here there’s a theme. In traditional fashion, markets, and needs, and strategies, are really defined around solutions to technology as opposed to being customer centric. So we’re going to show you that customer-centric and view is the same thing, so let’s go through this.

How markets are typically defined? Well, they’re usually defined around a product or technology. The LP market, the CD market, the 8 track market, if that’s a market, the MP3 market, and these technologies, of course, come and go over time, but the interesting thing is that when these technologies go away it doesn’t mean that the underlying market disappears, there’s still something there, right?

The products come and go but the underlying market is to get a certain job done. People have been trying to listen to music forever, and what we see happening is better and better technologies come along to help get the job done better. This is one of the key steps in understanding where to go with all of this. If we can focus on the job, and define the market around the job, define the needs around the job, you can dramatically reduce the risk of failure in your products.

Now, this is hard to do, I’m going to tell you how to do this, but this mind set, this shift of being product-centric, to become customer-centric is really hard, because we’ve been trained to think about solutions our whole lives. Our first instinct is to come up with ideas, our first instinct is to solve the problem before we truly define the problem, and this is all part of the discipline that has to come into play in order to make this right.

So the very first thing we do is define what the market is.

The market’s a group of people who are trying to get some job done, the way we talk about it, and we have to decide who is the key customer, who are we trying to create value for?

In many cases this is a quite difficult decision to make. There are people who use the product, but there’s people who buy the product, there’s people that influence purchase decisions, people that install the product, there’s people that repair the product, they maintain it, they upgrade the product. There’s lots of elements that are going on here, so how do you begin? How do you ensure that what you’re working on is going to have the greatest chance of success in the marketplace?

There is a formula for this, and the formula says that true value is best created for the person who’s using the product to get the job done. That’s the person around which the market exists. Of course, you have to install the product, you have to upgrade it, you have to maintain it, but people aren’t buying products so they can install them, upgrade them, and maintain them. They’re buying products to help get some core functional job done, so focusing on the job executor makes great sense.

Also, in many cases the buyer is not the user of the product. We made this mistake back at IBM, we though ComputerLand was our customer. Anyone remember ComputerLand? Yeah, it was a bad mistake, and we were wrong, right? Of course, it’s the person using the product to get the job done that’s the customer. The buyer is a critical part of the equation, of course, because they’re using some set of financial metrics to decide which products are better than others. That’s critical, but it’s not the primary thing you want to focus on when you’re starting out with the innovation process.

I’m not saying that any of these things are unimportant and what I’m saying is, when it comes to customer innovation, our primary importance is the person who’s going to use the product. If you can’t create a product that’s going to get the jobs done better, then nobody’s going to want to buy it, then nobody’s going to want to install it, nobody’s going to want to maintain it and upgrade it. So in terms of priority, let’s focus on who’s going to be using the product to get the job done.

So again, this is the way we define the market, by a group of people who are trying to get a job done. All right? A group of people, job done. Music enthusiasts listening to music. Parents passing life lessons on to their children. There is literally, of course, hundreds of thousands of markets, and the first step is to define the market around this format, and what this allows you to do then is actually analyse this market through a new lens, because you can actually talk to music enthusiasts about this job of listening to music, and you can break it down step by step so you can understand what metrics people use to measure success in getting the job done. So that’s exactly what we do.

This is called a job map. It’s different than a process map; it’s different than a customer journey experience. It’s what the customer is trying to accomplish, which is distinctly different from what they’re probably currently doing. What they’re doing is probably a lot of work arounds, and making do with what they have, and they’re probably cobbling together lots of different solutions to get the job done.

We don’t want to lay out what they’re doing, we want to lay out what are they trying to do. In any typical job, they’re trying to plan something out, they’re trying to gather all the inputs necessary to execute the job, they’re trying to organize in some fashion that will make them work together, then they confirm that everything’s in place to make this happen. They then execute the job, and while executing, they monitor the execution to make sure the job’s getting done correctly and the output is right.

Next up, they make modifications as they go, and then conclude. We’ve analysed hundreds of jobs over the years and they all follow this similar pattern, but of course, we apply it to each situation. In the case of listening to music, you may want to decide what do I need the music for? Am I throwing a party, am I trying to relax and go to sleep? What is the situation? Then I need to gather all the music I want to listen to for that time period. I need to organize it in the right fashion, confirm that everything’s ready to go. I get to listen to the music, make modifications, add, subtract songs as we go, and assess my experience at the end.

The reason we create the job map is because once we know what the job is, we can envision the solution of the future. The solution of the future will get the entire job done because people don’t want to have to cobble together different solutions to try to make this happen. This is why all markets work. All markets evolve towards helping customers get a job done. M & As occur because people are trying to put together pieces to get more of the job done.

This is just a general trend in the way people think about their extensions and their adjacent markets.

When you start thinking about this, you think of CDs and LPs, for example, they only get part of the job done, they allow you to listen to the music. But it took a long time before iPods came along and helped get a lot more of the job done, and what this shows you is that once you come up with a technology that get more of the job done, it gets adopted for use, but it has to get a significant portion of the job done better before it gets adopted for use. It can’t just be a little bit better. Then you see streaming services come along and get more of the job done better, and they get adopted for use.

So this is the thought, if you can define what that job is, you can envision the future, because the ultimate solution will get that job done. Now, it may take decades before you can figure out how to do it. In the software world it should only take, what? A couple of months, right? You guys can do it that quick? It’s a little easier than the hardware world, I suppose, but you can envision the ultimate solution because you know it has to do all these different things.

So the goal then is to figure out, how do we get there? I see what we have now, how do I get it to execute all these different steps and to help customers get the entire job done?

Well, that takes us into the next step, how do I know I’m helping to get the entire job done? This is where we start defining customer needs.

When we think about needs, we think about a very specific metric that are people using to measure success when getting the job done. That’s the way we define the need, so we have a very specific definition. Again, it’s the metrics that people use to measure success when getting the job done. We call them a desired outcome. Its outcome driven innovation because everything’s built around knowing what these statements are. They’re measurable, they’re controllable.

We spent a couple of decades trying to effectively define and optimize the way we structure an outcome statement. This is really the key to success and innovation, is getting good inputs. It’s really the key to success in any process, have good inputs that don’t introduce any variability into the process. We spend a lot of time figuring out what does introduce variability into the process and how can we successfully eliminate it.

So these statements have very unique characteristics. One is certainly, they’re devoid of solutions. They don’t talk about technology, they don’t infer a solution in any manner, they’re solution agnostic, or independent. Because in the end, we’re going to test the solutions to see how well they address these metrics, and in any good equation, if you start mixing up constants and variables in the equation, you can’t solve it.

So we have to be very true to the fact that these statements are solution free. They’re also stable over time, which is intriguing because we all learned that customer needs are ever changing, and they’re latent needs, and people don’t even know they have them. But people do know when they’re trying to get a job done, and they do know when they’re measuring success each step of the way. Now sure, people didn’t know they needed a microwave oven, but they did know that they were trying to minimize the time it takes to cook a dish, and minimize the likelihood of over cooking a meal, or under cooking a meal. They knew all those metrics, they’ve know those metrics for decades, but they didn’t know that a microwave was a better solution to get the job done.

So we think about these statements as the glue that holds the innovation process together. You can see how they’re formed, again, very specific. Minimize the time it takes to determine how much music will be needed. When gathering the music, minimize the time it takes to determine what songs to include. When organizing it, minimize the time it takes to determine the order in which to play the songs. Minimize the likelihood that the music sounds distorted. Minimize the time it takes to remove the songs you no longer want to hear. Now, all these statements are true today, they were true five years ago, they were true 25 years ago, they’ll be true five years from now. The reason is, all these statements are built around the job. The job’s exactly the same; people are still trying to listen to the music. What’s changing over time are these different solutions that come around to help people get the job done better.

The solutions are the variable in the equation; the outcomes are the constants in the equation.

Again, if we can identify the constants in the equation, we can systematically test solutions to see which ones address them the best, and pick the best solutions to go work on and increase our chances of being successful in the marketplace. So that’s the ultimate goal. Of course, getting these statements is not simple, but customers do know that this is how they’re measuring success. If you lead customers down the path and ask them the right questions, you can come up with these answers.

Let me give you one hint as to how that’s done.

The only way to get a job done, more predictably, without any variability, and with high through put, or output so there’s not waste, it’s 100% efficient. So ideally, it’d be extremely quick, no variability, 100% trough put. So knowing that, we ask questions around those three different possibilities. What makes executing a specific step time consuming? What makes executing a specific step go off track, unpredictable? What makes it inefficient? What causes waste? Asking questions like that help you understand and help get you in the conversation of describing these outcome statements.

The third piece of all this gets into the strategy itself, now we have the inputs, right? The beautiful part about having these outcomes, and by the way, there’s usually between 50 and 150 different outcome statements that describe success when getting a job done. It’s not like customers have one or two needs, or five or ten needs, it’s usually that there are between 50 and 150 different metrics that they use to measure success in getting the job done, and you want to capture all of them, right? You don’t want to miss any because you don’t know where the opportunities lie.

You can’t manufacture an unmet need, you can try, but it’s really hard. It’s actually a lot easier just to go satisfy an unmet need instead of trying to manufacture one.

If you do this correctly, you want to cast a very wide net, and make sure you understand all those needs, and then you can figure out precisely what one’s to go after, which is where we go next with all of this.

This is done in a more quantitative fashion, and the goal here is to figure out which needs are unmet and which ones do I want to go target. This is really the essence of strategy, this is the decision point at which your company is going to either succeed or fail. You sit there and pick, what unique value am I going to bring to the marketplace? Which set of unmet needs am I choosing to go address that nobody else is addressing, that’s going to differential me from my competition?

Now, getting this right and getting it wrong, again, is the difference between success and failure in your market, so getting it right is critical. Let’s say that there are 100 needs in the market, and let’s say that there are ten unmet needs. What do you think the chances are of anyone in your company randomly coming up with a solution that addresses all of those ten unmet needs, if you don’t know what those ten unmet needs are? Pretty slim? They’re about one in 14 million, so that is pretty slim. Still did the lottery? It’s better than that, slightly, that is true.

So we want to mitigate that risk of failure, right? So how do we figure out exactly which of those needs are unmet, because we want to get our strategy right? Well, this is best done quantitatively, and I’m showing you here what we layout as we call an opportunity landscape. That little dot on there is one desired outcome statement, and behind that one dot, we’ll ask anywhere from 180 to 360 people to rate the importance of that need and the level of satisfaction, and then what we do is we plot it out on here.

So here, 81% of the people that we inquire with say that needs are a four or five with importance. It’s extremely important to 81% of the population, yet only 30% of the population is satisfied with their ability to execute along that dimension in this particular market. So all this gets plugged into our opportunity algorithm, and everything that gets plotted over here in the purple space is considered an unmet need.

So the math helps us follow through and figure out which needs we need to go focus on, so this lays out the landscape. In any given market there are needs that are over served, there are needs that are under served, and there are needs that are appropriately served, and the chances of you getting this right by guessing are very low. Once we quantify it, you can figure out very quickly, exactly where you need to focus to get the job done significantly better, and this is the difference in many cases between success and failure in the market.

So let’s talk more about this because a couple of things we discovered as we progressed on this path over the years is that not all job executors are alike. In other words, not everyone is going to agree in your market, which needs are really important and poorly satisfied. People think about the job differently, they execute it differently; they use different solutions to get the job done.

A good example here, we’ve worked with companies in the automotive space and interviewed people about all the jobs they’re trying to get done while driving, for example. There are jobs such as making sure you don’t get lost, or making sure you don’t make a wrong turn, or make sure you don’t get stuck behind a vehicle, there’s a whole bunch of things, but they all roll up into this bigger job of making sure you reach your destination on time. Now it’s interesting because we all have to reach destinations on time as part of our regular work routine, but some of us go to work at the same place each day at the same location. We know the traffic patterns, we know the backup routes, and we know exactly where we need to park, so we don’t struggle to get the job done.

There are other people, each day, which have to travel through different parts of the city, they don’t know the backup routes, they don’t know the traffic patterns, they don’t know where to park, and they struggle to get the job done. So, same group of people, same job, and some people struggle a lot more for some reason, and some people struggle a lot less for some reason.

What this helps us figure out is that in many markets there are segments of both under served and there’s segments that are over served, and this is very significant when we want to figure out who do we want to target with our product and services to make sure we’re successful in the market, so we’ll get into that.

Now, the key thing here about segmentation is that traditional segmentation doesn’t work for innovation. So if you segment your market around demographics, sycrographics, typical behavioural characteristics, it really doesn’t help to determine differences in customer needs, and we’ve proven this over the years, we’ve done hundreds of studies, we have thousands of charts that look something like this.

Oh, there we go, there’s a little delay. We know, for example, that gender doesn’t reveal unique differences in customer needs. We know that age does not reveal unique differences in customer needs. We know that region of the country does not help us, this is slowing down a little bit, reveal unique opportunities in customer needs, and we know that business size does not, as well. In fact, I could put 100 slides up here that show all the things that don’t reveal differences in customer needs. And it makes sense, because if you’re trying to find out differences in customer needs, the only thing you can segment around is customer needs.

Up until now it’s been very hard to segment around needs because there’s no agreement as to what a customer need even is. So, if we don’t know what a need is, how can we collect them, how can we agree as to what they are, how can we prioritize and segment the realm? Well, you can’t, and that’s been a huge problem, but once you segment around these unmet needs, it reveals a very different picture of the marketplace. And this is, what I think, is probably the most powerful part of our whole process, and it’s really led us into some significant findings in the way markets are typically defined.

There usually is an underserved segment of the market, there usually is an over served segment of the market, and often times there’s something in between. We’ve seen plots of markets that are all around this particular graphic, and the key here is once you’ve seen how the markets defined, you have to decide who you want to target. Do you want to go after those groups of people who struggle to get the job done, and are willing to pay more to get the job done better, with brand new platform level solutions? Do you want to take a current product that’s out there and tweak it a little bit to make it a little bit better so you can satisfy some of the unmet needs of the segment that’s slightly under served? Or, do you want to go after the over served segment and come up with a lower cost solution that gets the job done, potentially even worse, at a lower cost?

These are the key decisions that you have to make, and they have a dramatic impact on the kind of product that you’re going to create. And the interesting thing here is, you don’t really get to pick, or at least correctly pick what strategy you’re going to pursue. If you’re going after a segment here in the bottom-right, then that suggests that they’re really struggling to get the entire job done. Adding features to current products really isn’t going to do the trick, you need a brand new platform that gets the job done significantly better, and it has to be re-thought.

Going after the segment in the middle, you don’t need to create a brand new platform. What you need to do is just add a few features to the current platform to get the job done better. And the one on the left, it’s over served. If you add features to the platform to get the job done better there, you’re just going to lose. That’s a losing strategy right from the start, so you don’t want to pursue that.

So knowing this, and we’ve laid out these different kinds of strategies over the years, and we let the data dictate what kind of strategy a company should follow, so I’ll give you a few examples. In this case here, this was a company called Bosch, they make a whole variety of things, but they wanted to enter the North American market with a circular saw. They had skill saws, but they wanted the high-end Bosch brand name in North America, this was back in the early 2000s.

Now, circular saws have been around for quite a while, 80 plus years. Commodity type products, how do they win in this space? Their goal was to figure out, are they any unmet needs? If you looked across the market prior to segmenting, and you looked at the average, there were no unmet needs. But by segmenting the market around the outcomes, they found a segment that looked like this, had 14 unmet needs, and they worked to satisfy all 14 of those unmet needs so they could help the customers get the jobs done significantly better. And they did that and they came up with the solution called the CS20 Circular Saw, it’s still their best-selling saw in North America, it’s been at that for eight years.

Now, the interesting thing here is, again, you can’t manufacture an unmet need, there are only 14 unmet needs. One of the first questions they asked was which one do we go after? It’s not which one, its which ones, you want to go after all of them, because you can’t create a product that just gets the job done a little bit better, all right? If you’re going to win in the market, you have to get the job done a lot better.

Think about yourselves. Would you switch from a favourite brand, or a different product, or pay more for a different product that gets the job done 1% better? Or 2% better? Probably not, but maybe 20% better? 30% better? At some point you’re going to go, yes, I would be willing to attempt to use another product to get the job done if it promises to get the job done significantly better.

So this is where we have to go. Now, how long do you think it took the Bosch engineers to come up with a solution to address those 14 unmet needs? Any guesses? A year? Six weeks? Any other guesses? How about at the other extreme? That’s closer to it, it took about a half a day, and it took about three to four hours.

The reason was, they already had all the ideas, they’ve done this for 30 years, they had every idea, but the problem was they had thousands of ideas, thousands of them. They didn’t know which 14 they should combine in a circular saw to get the job done best.

Again, what are the chances of randomly coming up with a solution that addresses 14 unmet needs if you don’t know what they are? You can’t do it, but once you know what they are, you can put the solution together that gets the job done significantly better, and win in the marketplace.

Now, I like this example for two reasons. One reason is, it shows you the level of precision that you need in order to win in a commoditized market place. Then it shows you the level of precision that you can get using this tool set to identify, precisely, those 14 unmet needs in one segment of the market, which is often what it takes to be successful. That’s the whole point. Guessing shouldn’t be an option. You don’t want to guess at your future, you’re here, you don’t want to waste your time, you don’t want to waste your careers, you don’t want to work on PC Juniors, and you want to work on winning products in the marketplace.

Of course, most markets don’t look like that, some look like this, where they’re pretty satisfied, and adding features to the current solution to get the job done better really is not the right thing to do.

This was the case with Kroll Ontrack. I see a hand up for questions. What I’m going to do is, we’re going to have a Q&A for about 20 minutes after this, so if you have some questions, just jot them down and make sure we get to them. Now, in the case of Kroll Ontrack, they were trying to enter this electronic discovery market, or create it basically. Prior to this, people would do discovery by hand, they would go into companies and read through papers, and they’d try to find the evidence to build a legal case that was ultimately the goal. What they did was they discovered a solution that could help people get the job done, initially, not quite as well, but for a lot less cost.

So they built this platform and they’ve been building it out for the last 12 years or so, and still today they lead the industry. The way they did this is they got all those needs, they laid them out in priority order, and year one, they’d come up with a solution that addresses the top 40, next year the next 20, the next year, the next ten, and so on.

It gets very hard for companies to leap frog them because they are systematically working to get the entire job done on a single platform, which should be the goal. So, this is a great software solution, and again, the concept is exactly the same, help customers get the entire job done on a single platform so they don’t have to cobble together lots of different solutions to make it happen. Of course, all markets don’t look like that either. Sometimes you see a situation like this, as we did work in Microsoft Software Insurance space.

People were satisfied with one job that the product was initially designed to perform, and the way to win here, if your market is satisfied along all these different dimensions and appropriately served, the only way to help grow a market in this case is to add features to the platform to get more jobs done. So now you have to think about more jobs. This is a great little device here too, to think about this concept. What was this device 20, 30 years ago?

It’s just a pointer, right? Is this a pointer? I’m not even sure, but this was a pointer years ago. But as time progressed, these devices became more sophisticated, they’re used to change slides, they’re used to darken the screen, they’re used to tell you how much time you have left on your presentation, they get more jobs done.

The same thing was true with Microsoft. IT managers are trying to get other jobs done that were under served, they just had to discover them, figure out which ones they are, lay them out in priority order, and add solutions to their platforms to get more jobs done. Which they did very successfully, generated by the additional billions of dollars in revenue for them, by doing it in this fashion.

The last one is really my favourite. This is, I think, the hidden opportunity for all of us. I find this intriguing, because in almost every market there is, they have the underserved segment. This is a group of people that for some reason, struggle more than anyone else to get the job done better. It could be that group of people, for example, who are struggling hard to reach their destination on time, or to pass on a life lesson to a child, or to listen to music. For whatever reason, they’re struggling more than anyone else. This segment of people, if it exists, if usually willing to pay more in order to get the job done better, so this kind of segment offers a great possible opportunity for you. It allows you to enter into what we call a profit-share strategy.

Now, this kind of strategy, I think, is probably the most profitable strategy companies have, and many of the bellwethers of innovation are doing exactly this. So, if you can think about Nest, for example, fairly new to this game, but think about this. Here’s a company that’s never created a thermostat before, getting into a new market, the chances of success are extremely low. But what do they do? They not only get into the market, but they are charging seven times more than anyone else for a product to get the same job done. Everyone else is at about $35, they’re at $250. And you can think how many people are crazy enough to spend $250 dollars on a thermostat? Anyone here?

Well, you look at the numbers and it matches what we’ve found here, about 8% of the population is crazy enough to buy that for $250, but what that does for Nest, is it generates about 30% profit share in the industry for them, which is fantastic. That makes them, immediately, a huge threat to all the other manufacturers in this space, because as they start taking that product and making it better and better, and taking that product and dropping its price, it’s a huge threat across the board to everybody. It’s a beautiful strategy.

Dyson, of course, did this years ago with their vacuum cleaners. They charge about five times more, and with about 20% of the market share, they have about 59% profit share.

Of course, Apple is the best at this. A great example, 12% market share, 70% profit share. Now I think this is where you’d like to be as a company, figure out is there a segment of the people that is highly under served and willing to pay more, a lot more in many cases, to get the job done better, and we’ve found examples of this in literally every market. Every now and then there isn’t the opportunity, but in most markets there is a segment of people who are struggling more than others.

The key is, why are they struggling more? You have to figure that out, that’s where the segmentation comes in, where the unmet needs come in. So, I think this sums it up, right? What we’ve done is we answered all these key questions before we even had an idea, all right? We know who our customer is, it’s the job executor. It’s not the buyer, it’s not the installer. What problem are they trying to solve? We know the functional job that they’re trying to execute. We’ve broken it down step by step and we know all the metrics they’ve used to measure success along each step of the way. We take those needs, we quantify them, and then we can figure out which segment of the market we want to go target. Is there that highly underserved market that’s willing to pay more to get the job done better. And then from there we know precisely which unmet needs we want to go target, In the case of Bosch, these 14 unmet needs, perfect. So that’s the goal, and a I mentioned earlier, it only took the Bosch engineers a half a day to figure out the answer, but it took them years to figure out the problem, and defining it in such a precise way that they could address it.

That’s really the key to success here, is doing it in this fashion, and the goal here is to get the job done significantly better. When iPod came along, it did get the job done significantly better, it got more steps in the job done which was great. But of course then Zoon comes out a number of years later, interestingly, the same year Pandora came out. Now this is interesting because Microsoft could have gone down either path. They could have went down the MP3 path, or they could have went down the Pandora path, and here they are coming out with a copy product that doesn’t get the job done any better, in a time frame when there is a new technology coming out that gets the job done significantly better.

This again, the product-centric focus doesn’t necessarily win, but focusing on the annoying job will better increase your chance of success, which is the whole point. You don’t have to gamble on innovation, right? You don’t have to walk the organization, unsure of what the customer’s needs are, and having discussions, in many cases, heated discussions with your peers as to what the product should do and why it should do it. I know many companies where you spent a lot of time doing just that. If you can’t gain agreement in what you’re trying to accomplish as a company, it’s going to be a lot harder to succeed.

So, to pose a question then, do you want to be an ideas-first company and just brainstorm solutions and hope that they’ll succeed in the marketplace? Or do you want to be more disciplined and take a different approach, where you can lay out, literally, lay out a road map that allows you to measure a possibility of success? And that’s up to you to decide. Now with that, I’d like to take whatever remaining time for some questions. APPLAUSE

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.

Audience member 1: Thanks, you gave examples of individuals like music enthusiasts listening to music, how do you translate that into a B2B kind of arrangement where am I thinking of the whole company and the job they’re trying to execute, or a person within that company. If I’m trying to sell that company a product, am I really selling the owner of the company that product, or a specific person? How do I translate into more to a company situation?

Tony: Yeah, that’s great. In the B2B case, the same set of principles is applying. So, in B2B, you mentioned the two scenarios, right? Am I selling to the executive? You may be, but you’re selling to the executive because they’re the business decision maker and making the purchase decision, so they’re responsible for making sure that job gets done. But you’re trying to sell them a product that someone else is going to use to get some other job done. Maybe it’s the process engineer to try to help improve efficiency in the process. Well, if you’re going to create the product, you’re going to go to process engineers, who everyday think through this job of making a manufacturing process use more efficient, and you’re going to discuss that job with them, break it down step by step, figure out where they’re struggling to get the job done better and applying everything we talked about here. But it’s known that they’re playing different roles, right? The executive, yeah, you’re going to have to sell him at some point, so you’re going to have to convince him that you’re creating enough value here that’s going to save time, money, resources that they’ll want to buy the product. But you’ll have to create the product first to make sure it does actually achieve those goals.

Audience member 2: Tony, great presentation, thank you very much for that. Those graphs that you showed, beautiful graphs, it’s very easy to determine where you should go after. Can you give an example of how you create one of those graphs, what you’re asking, and how you’re plotting the dots? It seems like a very subjective graph, so maybe some structure on that would be great.

Tony: Yeah, it’s not subjective at all, we call it the opportunity landscape, and it plots out importance and satisfaction. We put a survey together and we ask any where from 30 to 1,000 people to rate the importance and satisfaction with each of those needs. They’re rating it on a five point scale, they’re telling us their level of importance first, level of satisfaction second, and they go through all the questions and answer them. So then we roll up all the individuals and we plot them on there, and again, the equation shows the percent of people that are rating an outcome of four or five for importance, and a percent of people that are rating an outcome of four or five for satisfaction, and that’s what gets plotted on the chart for each dot.

Audience member 3: One question about that slide where you had all the different steps that define the job, from gathering to executing. The question I have is how the company behind the solution fit into that does. It seemed they’re feature-centric, to me, but in a mature market, especially, where there’s more than one solution that does a lot of the job, then people start looking at who’s behind this, are they going to stay in business? How do you plot that in to the chart?

Tony: Well, you don’t plug it into that chart because you don’t even answer those questions until after you’ve created the successful product, because the answer is nobody’s going to buy your product if it doesn’t get the job done a lot better. So, no matter what your name is, if it’s Apple, or Nest, or anyone, right?

The key is, and the very first thing is, you’re product has to get the job done significantly better, and then you have plenty of time to think about answering all those other key questions. How do I get it to market? How do I message myself? Those are all go to market kinds of things, and they’re critical in terms of go to market, but before you get there, before you worry about that stuff, come up with a break-through product. Make sure you know that the product that their working on is going to get the job done two, three times better, and 20, 30% better and then you can address those later. Yeah, I think that’s an important point.

Think about it in a sequence, innovation, development, go to market, all right? Let’s worry about innovation first, because if you don’t get this right, you’re just going to be spending a lot of time downstream. Question up here.

Audience member 4: You mentioned a rule of thumb of between 100 and 150 outcomes per job, I’d like a bit more background because I find that useful to have that, but jobs are so different. I’m just trying to apply it to what we do, and it seems strange that you can actually apply a rule like that to such a wide variety of jobs.

Tony: And that’s why it’s such a range, too, 50 to 150. When we do surgical related products or medical related products that ends up on one end of the scale. As you go through surgical procedures, there’s so many things that surgeons measure in success of getting a job done, that pushes it up towards the 150. If you’re talking about cutting wood in a straight line, in the case of Bosch, it’s a lot simpler, that was more towards the 50.

But just over the years, we’ve done hundreds of these projects, obviously, and that’s the general range. The real point is that it’s not five, or ten, or 15, or 20 needs, and that’s what companies usually think, or they try to limit their quantitative research to 30 statements because they think the user’s going to get fatigued somewhere in there and not be able to give them good data. That’s all not true.

We execute a survey with over 100 outcome statements in it in less than 25 minutes, and we’ve been doing it for years.

Audience member 5: Building off this gentleman’s question, back to the Bosch example, how did they determine the dozens, or hundreds of different outcomes to ask about in their survey and who did they survey? Did they survey circular saw users? Like, who was it they survey and how did they come up with that list of outcomes to ask?

Tony: They did that through Qualitative Research, there was one on one interviews and so on, and just all the typical techniques, ethnographic research. These days it’s often done online too. There’s so much written about every product and the jobs they execute, you can get a lot of insights from there as well. But that’s done through qualitative work, and it’s done by asking key questions. The way we typically do this is we work with a few executors to define the job map. What is the job from their perspective? Once we know the job map, then we start filling it out to figure it out how do you measure success along each step of the way? What makes this step time consuming, unpredictable, and inefficient? And just work our way through that, so it’s done through a series of interviews and we just systematically fill it out. It typically takes anywhere from ten to 20 interviews depending on the complexity, to get the entire set of outcomes uncovered. Question over here?

Audience member 6: Many of us work in markets that are not very well understood yet, like completely new markets. So if we make a new product, there’s no existing product like it yet, so it’s quite different from the existing things. Can you walk us through a story of someone who used this technique to write a product completely new from scratch?

Tony: Sure, and that’s a great point, and the beauty of the approach is that you’re actually at an advantage working in new markets, because you’re not going to be product-centric, because you can’t be. That’s great, that’s actually an advantage for you.

And the other thing you probably think is, if there are no products, can you go get this information? Let me ask you this question, how many of you are parents? Quite a few. How many of you are trying to pass on life lessons to your children? That’s good; it’s about 90% of you that wasn’t there. Mental note. You’re trying to get this job done, how many of you have products that help you get the job done today?

So here’s an example, all right? So here’s a group of people that are trying to get that job done, do you think we could interview these people and figure out how they’re measuring success along each step of the way to get the job done? I’m sure we can, right? And this is the beauty of it, you don’t have to be encumbered by these other concepts that there are latent needs, or you have to show them a product in order to get their feedback. it’s just not true. Just go through step by step to figure out what do the parents have to go through in order to pass on life lessons to their children, and find the right learning moment, learn how to say the right things, not miss opportunities, and reinforce over time. You can lay out the job and what needs to be done, and if any of you want to create a product that does that, I think there’s a pretty good market for that, or what it appears to be. Okay, question here?

Richard: Hi, Tony, this is Richard. You know, a lot of the examples you showed had to do with bigger companies attacking the established market. You know bigger companies have strategy teams, they have tons of resources and they have a lot of history of research, as you mentioned in the Bosch case. A lot of us in the crowd have small bootstrapped, growing businesses, you know, we’re putting out fires, how would you say we should go about the ODI, or the outcome driven innovation work that you’re recommending here? What tips do you have, what tactics do you think we should apply?

Tony: The bootstrap way, and its all level of risk, right? But trying to mitigate a chunk of risk, and doing it this way is better than not doing it at all, right? So let’s say, bare minimum, what you want to do is if you have a good job executor, maybe someone that is your target customer, a friendly customer, in essence, work with them to create the job map. Do that thing first, sit with them to figure out what is the job you’re trying to execute.

Again, following the rules is a little tough. Again, you’re going to write down what are they doing and you’re going to catch yourself and go, okay that’s what they’re doing. What are you trying to do?

Let me get behind that. Why are you doing this? I’m trying to get behind it to figure out the exact thing you’re doing or trying to do. Work with a customer to do that. If you can just do that, if you just know what the job is that they’re trying to execute and you have a good vision of all the steps in it, you’re going to be way ahead of where you would be if you didn’t have that information, because now you can envision the ultimate product, then you need the rest of the details to try to get there, but at least you’re heading off in the right direction. I think a job map helps a company realize its long term vision, because its goal is to create a product that does the whole thing, and they’ll figure it out over time. So if you at least have the job map, put it up on your wall in your war rooms in your businesses, and you can look at that each day, and everyone’s pointing in the same direction, it helps you make decisions, write trade-off’s, all those sorts of things. So, if nothing else that would be a good start.

Audience member 7: It seems pretty straight forward for functional jobs, how easy is it to apply this to social and emotional jobs which it’s a bit harder, I would guess; maybe your experience is different to figure out the answer?

Tony: Sure. The question is, you can see how this works for functional jobs, but how would it apply to social jobs and to emotional jobs? I love this question because you don’t create a product to execute an emotional job as our conclusion. You create a product to execute some functional job, and you position it around emotional jobs. We never actually break down an emotional job to figure out everything behind it, because you can’t create a product to satisfy an emotional job.

You can’t create a product to make someone feel cool, or to be perceived in a favourable fashion by someone else. Now, I’m not saying these emotional jobs are unimportant, we always capture them, they’re a critical part of the equation, but you can’t create a product to satisfy emotion that’s void of function. It has to do something a lot better, even if it’s a medical device, or even if it’s an IT device. That’s good news; we’ve done a bunch of work in the IT space. We did discover that IT Managers do have emotions, so that was, I was a little surprised, I don’t know about you guys. But bringing them into the equation, I think, was critical, and what we in the end, we do this, what we call an emotion function correlation analysis. So we look at the function that we’ve created, or the unmet needs, let’s say in the Skill-Bosch thing, for a quick example.

You come up with these 14 unmet needs; you create a product that actually addresses them. So you know you’ve got a product that addresses the need of 14 things. Now you want to figure out, since I’m satisfying these 14 things, what emotions am I appealing to? So you do the correlation between those and the emotions that people are trying to achieve when getting the job done, and now you can start building your marketing message. That’s the way we apply it, but a lot of applications that I see when people are trying to do jobs-to-be-done, they try to define the job around this functional and emotional element and combine the two. That’s a mistake, it will throw you off track because you don’t have to get to the emotional stuff until after you actually have a product that does something functionally sound and significantly better than other solutions, so don’t fall into that trap, and I think that might help. Hopefully that’s good.

Mark: Fabulous stuff, thank you very much. APPLAUSE

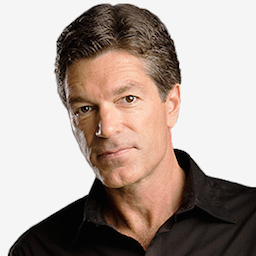

Tony Ulwick

Tony Ulwick is the pioneer of jobs-to-be-done theory, the inventor of the Outcome-Driven Innovation® (ODI) process, and the founder of the strategy and innovation consulting firm Strategyn.

As an innovation expert, Tony has helped hundreds of product and marketing teams in leading companies use ODI to create breakthrough products and services.

He is also an author, speaker and entrepreneur.

Next Events

6-8 October | Raleigh, NC

Grab Early Bird Tickets

13-14 April | Cambridge, UK

Grab Early Bird Tickets

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.