How can you take a team of infighting execs, each with their own goals and turn them into a disciplined team with a single shared purpose?

As you evolve, priorities may change, but the need to keep your team focused on the big goal (singular) of your org is a constant challenge for founders and professional leaders alike.

In this talk, Bruce shares the core principles you need to understand your stakeholders, negotiate priorities, set and manage the metrics that will drive your teams forward together in pursuit of the strategy you have set for the business.

Slides

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.

Transcript

Bruce McCarthy

Hi everybody! Some of you know me, I am a product coach, I help companies get better at product, I help them hire the right people, organize them properly, teach them skills, and sometimes end up as kind of the organizational therapist too. And so that’s kind of more of the side of the conversation we’re gonna have today. Also, in the very dead center of our audience today is another member of my team, Phil Hornby, Phil, raise your hand. You can see he’s got a white lanyard, so you have to talk to him, and be nice to him. Although he’s got no problem with that, he’ll probably come up and talk to you. Right? Yep.

So I’m going to talk about the difficulty I’ve seen over many years of working with clients, in getting everyone, particularly the executive team, aligned on the product strategy, or the company’s strategy or really anything. And not only how hard it is, but how critical it is to making progress on things. And I call this, you will find out in a couple of slides why I call this, the “No-No” case study.

“No-No” Case Study

Introduction

So I started off, it seemed fairly routine, like a lot of clients, they call me in for something fairly concrete and specific. They want skills, hiring, organizing, evaluation, something. In this case, this was a B2B SaaS company, a disruptor in their industry, they were taking a new approach had a relatively new platform. And they were doing pretty well. They had had about 250 employees, when I started talking to them, they were about 40% growth, they were not profitable. So they were a little behind the rule of 40 that Imogen was talking about yesterday. But they they felt like it was okay. But they want to do adopt OKRs, this is why we were talking, in order to try to accelerate that growth because they thought something would help them be more aligned and more productive and have more focused on outcomes, which is what OKRs are all about, right?

They had a seasoned executive team, all had done this kind of thing before. They were split between some in Europe, and some in the US. They had a new CTO who had just joined and he’d been asked to kind of reinjure not re energize the engineering team, which was perceived to be kind of self satisfied, if we will. Maybe not, maybe not being as productive as they could. So you’re seeing the theme here. They asked for help implementing OKRs and I obliged. And we started with a an executive team workshop to agree, what were the big priorities for the next quarter that we were going to try to put into some measurable format. We did the workshop, it was very collegial. They came to alignment pretty quickly, we rolled out the OKRs. So far, so good. Right?

Well, then I met their internal coach, they had an internal Agile coach who was not just limited to working with engineering and product, but was trying to work across the whole organization. He was going to be my inside man and helped me actually implement a lot of the things that we come up with. And when I first met him, I discovered he shook his head a lot. He was really skeptical that this was going to work. He was like, “I know OKRs. I understand OKRs. They’re great. They’re not going to work here.” And I was like, “Well, what what’s the problem?” He said, “You’ll figure it out, as we go forward. You know, they’ll agree to stuff but it’s not going to happen. You just wait.”

The Problem

So I waited. And here’s what happened. They started to have a series of outages of their SAS platform. Some of them pretty serious. It took them a while to recover. They weren’t doing good communication. And at the same time, they also missed their numbers for the quarter. And the two were unrelated. At least apparently, it wasn’t that a bunch of people left, they just weren’t selling new anymore. There was a bunch of background chatter that I was getting through my buddy “No-No” about people not being impressed with the leadership of the company. And lo and behold, at the end of the quarter, they had achieved 28% of what they set out to achieve for their OKRs, we always measure at the end of the quarter. And you know, good is somewhere between 60% and 80%, 28% is not good.

“No-No” and a bunch of the engineers and product managers were kind of on the disengaged side, they were, again, not really convinced. And there was a lot of finger pointing about, well, you know, your team didn’t perform, and you guys didn’t meet your goals, etc. So at this point, “No-No” is like I told you.

So it got worse from there. We went to work, we reset the OKRs. We tried to diagnose what wasn’t working properly. We reset a lot of things about the OKRs. I asked a lot of questions about what’s not working, we thought we had understood the situation. But by the end of the quarter, their numbers were still flat, their customers had to had more outages and we’re still unhappy. They made a change on the executive team, they asked the head of sales not to be part of the executive, the small team, if you will, the small council. And he got really pissed and left the quarter later. And more doubt started to creep in more outages. And at some point they had layoffs. And at that point, “No-no” was like and was threatening to leave. He was he was honestly talking to me about offers, he was entertaining from other companies. And I was quite worried about the company.

Conclusion: Summary

That was the low point though. And I’m happy to say that a couple of years later, and it did take that long, a couple of years later, their customers are now loyal and sticking with them. They are not accelerating from that 40% to more, but they have stopped their downward spiral and they are back on plan, at least. Their team is stable, although they have changed out a couple of executives. As of two years later, the CTO and the CPO, Chief Product Officer, the system is much more stable. They don’t have the same level of outages that they used to do. And critically, the executive team is now collaborating with each other on what do we need to do to meet our goals.

The Solution to the Problem

So what I want to talk to you about has how they got from there to here.

That’s what we’re going to talk about is what has changed in that time. And I wrote out a series of principles, these five, five principles. And and I’ve been doing a bunch of crosswords lately. And when I wrote them out, it was like, Oh, that’s a word.

And I didn’t have to massage it at all, I really wrote out an F word and L Word, et cetera. And it just came out to float. And I was thinking, Well, these guys had been sinking for quite some time. And somehow they floated to the top. And so that’s the story of how they floated to the top, there were five things that they did, that they got much better at over these two years.

F-L-O-A-T

One was focus. Another was leadership inside the organization. And ownership, ownership of results. And alignment, the title of my forthcoming book, which I will tell you a little bit more about before we finish. And lastly, teamwork. These are the five things that they got much better at over two years. And I’m going to walk you through them one at a time.

F-L-O-A-T: Focus

So let’s talk about focus, first of all. First, what do I mean by focus? I mean, putting your effort toward one or a few overriding objectives. Focus is not the only things you’re going to do. But it is the one or a very few things that you’re going to allow to override the other things, the things that you must not fail to do in a given period of time. Along with your day job, there the the most important things you need to change.

Let me give you a picture of the journey that they went on with regard to focus. So when I started with them in that first workshop, we had eight executives around the table, all in charge of some function or other and we came out of that room with seven OKRs.

Who’s a big OKR fan? Should you have seven OKRs for one team? How about one, right? Yeah.

And that’s when I told them. I told them best practice is one to a max of three for any given team, including the executive team. And since you’re starting, let’s start with one. But no, they thought they could do it. He said, No, we really need to do all these things. And we believe we can do it. Okay, I decided to let them learn from their mistakes like, like Joe Leech was tape was talking about. And lo and behold, and I might have been wrong, right? I might have been wrong, but I was not wrong.

They got off to a slow start in implementing things they had, as I said, Only 28% success by the end of their first attempt at OKRs. And they came back and then they started to have outages. So that distracted them. I would say that the fact that they had so many new initiatives going these eight different things plus day jobs, they took their eye off the ball on the basics, and that’s where the outages came from. They really had a bunch of old crufty tech debt that they needed to deal with. And they weren’t dealing with it because they were focused on all the new shiny stuff.

So over time, because of this, they learn to focus. The next quarter, I said, How about one?, and they said, Well, four, we’ll do four. And after that, they went to three. And after that, they finally got down to one, and now they do one every six months or so. And the last time I talked to them, they actually had carried over that one an additional six months, because they really wanted to focus on it. And I will tell you what that one is in a little bit. So there, they got much, much more disciplined about focus.

It’s not that they weren’t doing seven other things, it’s that they were clear on what the focus was on what the key thing was that they could not fail to do. I’m gonna give you for each one of these things, a tool that they use to help them along. But I’m going to tell you now, the tools are an aid. It’s the work that the team did with the tools that made the difference. In this case, okay, ours was actually a tool that helped them recognize that they were too scattered and weren’t focused, because it’s measurable. For those who don’t really practice OKRs. It’s a simple goal setting system. It’s got two parts, objectives, what you want to accomplish, and key results, how you will know if you have accomplished it, it’s got to be measurable. So you can see at the end of the quarter, did we or didn’t we? Or how much did we if we didn’t 100%. And they measured it and it came out really low. And that just gave them a simple mathematical way of evaluating. Well, clearly, we’re taking on too many things. Maybe if we do fewer, we can have a greater percentage of success.

F-L-O-A-T: Lead

So what happened then? The leadership thing turned out to be another problem. Once they realized they couldn’t do seven OKRs, they needed a way to decide, well, which ones are we going to pick? How do we decide what to focus on more than other things. And unfortunately, for this particular team, their CEO, let me give you the definition, it’s, I think there’s a good decision making process that you need to go through. I call it the participative decision making process. And this is it in essence. You got to listen to all sides. But then somebody has to own making a decision and making it happen. So that we put it put aside the arguments, the CEO kind of wanted to make everyone happy. And that’s how we ended up essentially with an OKR for almost everyone in the room.

And so that’s that was not choosing, essentially. There were OKRs for every department and there was no prioritization that we’re all equal. I tried to get them to prioritize, and they couldn’t do it. So I taught them about this participative decision making model where one person owns the decision, but is obligated to seek input from everybody else. And they appointed a decider. No surprise, it was the CEO, but he didn’t really want the job. The rest of the team kind of forced it on him. He was they were like, Look, you need to be the one who breaks the tie somebody needs to and it’s your job. So you’re going to be the decider.

And he decided to actually he was very clear, we’ve got these outages, we need to deal with it. We’re going to focus on measuring this our success in just giving better service to people, we’re going to focus on uptime, time to recovery and clear, timely communication with customers about status. And if we fix those three things, our uptime problem will be fixed. And that any effect was there one OKR with three ways of measuring it, right? They didn’t quite I tried to tell them that I tried to say this is your OKR let’s set aside the other ones. They didn’t believe me they had four OKRs plus this. But they did start to make some progress, because they had decided, because they had decided what was important.

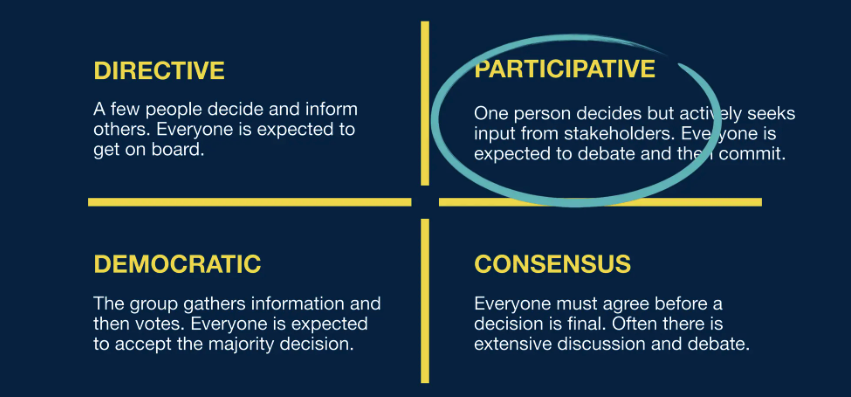

Decision Styles by Bain & Co.

So this is, by the way, this is from Bain and Company, this is the four different decision styles that organizations tend to operate. Had somebody seen this before? No? Okay, so directive is top down, it’s some one person, or some small number of oligarchs tell us what to do. And we are expected to just follow orders. This can be very fast in terms of making decisions. You know, organizations are decisive, but they don’t always make the best decisions, because they’re not seeking anyone’s input or advice, or consent. They’re just saying, Do this, do this do this. Product teams I work with hate this being told what to do.

Democratic is kind of the opposite. Democratic is we vote, we vote on everything. And there are companies that actually do this. And I think voting is okay, in the right circumstance, like where should we have the Christmas party? That’s fine. Vote, let’s vote on that. What should we call the conference rooms? Fine. Let’s vote on that. What should be our our product strategy? Probably not a democratic sort of decision. Right?

Decision Style “No-No”s Company is Doing

Then there is, I would say the most common type of decision making the the one that these guys were using without realizing it. And that’s consensus. That’s where everyone agrees. Consensus is, in my mind, more or less impossible. People in order to get everyone to agree, some people are either not caring, sure, whatever, or lying to you, about what about whether they actually agree. And I mean, just think about the last time you tried to get yourself and your in laws to agree where to go to dinner. Right, it’s just hard for everybody to be happy about a decision. So instead of trying to get to consensus, the participative model is that is the balance between these different forces is the I have the D as it is, the right to make the decision, so I could make it in a directive fashion. But I have the obligation to take input from everybody else who has either good information for me to make a better decision, which would be omitted in the directive case, or who is affected by or needed in implementation of a decision so that I have everyone’s perspective, but then I’m going to come back to you, and I’m going to make a decision. And probably not everyone is going to be happy. Unless they’re just happy to have a decision, which was what happened in this case, a lot of times, people are just more unhappy about uncertainty than they are about a decision that they don’t like. And that’s the situation they were in.

So the participant of one Bain has a bunch of statistics about why this is better for companies, they move faster, they get more done, they have better results. But I’ve just seen it in action with these guys and with others.

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.

F-L-O-A-T: Own

So then we got to the ownership piece. So these high powered eight executives, when the, when they got together, they decided to push the accountability somewhere else. They brought in a bunch of the directors that worked for them under this the bunch of C-level people and said you guys are in charge of the OKRs. Alright, you get this one, you get this one, you get that one, and they doled them out. But they were sort of abdicating their own responsibility. They became sponsors, executive sponsors for the for the OKRs.

But the directors hadn’t been part of creating these OKRs they weren’t sure why they were being asked to do this stuff. And they didn’t really have a whole lot of influence, especially across into other departments that were needed to achieve the OKRs. So they really didn’t get anywhere. And they the executives essentially gave away the accountability, the ownership for achieving the results.

When they began, they only did that for one quarter. Once they once they realized their mistake. They took the responsibility back on themselves. And they began to identify cross departmental blockers and talking to each other. Well, you know, my person from this team needs your help someone from your team, can we get them together? Yes. And things began to happen more the tool they used for this, the thing that convinced them that they needed to take the responsibility on themselves. While I was going to say it was this dashboard that I helped them make where they got together every two weeks and reviewed the progress they were making on these results. But really the tool was embarrassment.

They were embarrassed to report to each other that their team that they were sponsoring was not making progress. Everything was yellow, or red, except one thing, which is all blurred, as you can see, which people were reasonably reasonably happy with. They also had, you can see some health metrics and so on down the bottom. So that embarrassment or that, let’s say visibility, that’s a nicer way to put it made them want to take accountability and ownership of the results to improve them. And that actually worked.

F-L-O-A-T: Alignment

Then I want to come to the alignment piece. And this is where it started, they started to grapple with real issues, once they had solved the other basic problems of let’s narrow down to what’s really important. Let’s take ownership of these things ourselves. They began to realize the necessity for better tighter alignment on the executive team, they began to see the problem, if you will.

So I think that I would define alignment, as you know, in opposition to consensus as committing to a plan, even if you don’t agree. Being willing to say, I would do it a different way but I can see that we’ve all decided or the decider has decided that we’re going to do it this way, I will do my best to make it work. That’s the Jeff Bezos “Disagree and Commit” sort of thing happening right there. And they had a hard time with this, this was maybe a big nut for them. Because they disagreed a lot. They had started with sort of every department gets a goal. And that was easy, right? Marketing, knew what its metrics were sales knew what its conversion needed to be, et cetera. And then we’re working on things like increasing average order value, and increasing billable hours and reducing downtime, every department had their thing to do. And if they would just each perform, it would all be great. But A they didn’t all perform as you saw with the numbers, and B that didn’t even when they did it didn’t solve the problem.

So they began to drive alignment, when they finally started to look at it instead of internally from each of their points of view. Instead, from the customer’s point of view. The thing that started going down this path was looking at their business holistically like a customer does, their entire experience is, well there’s the app and it works or it doesn’t, it’s up or it’s down. And I can get an answer quickly to a problem, or I can’t, all of those things are the customers experience, the pricing, the renewal all of it. So they eventually when they got down to one OKR? That OKR became, let’s increase customer confidence in us. And they had a bunch of measures, some of which I already showed you that was there one OKR that they could align around.

The thing that convinced them the tool that helped them start to speak across the aisle, if you will, from one department to another was they use the Lean Canvas? Who’s seen this before? Lots of you, right?

They use the Lean Canvas. What’s great about it is it tries to bring all the moving parts of the business, who’s the customer? What problems do we solve? What’s our unfair advantage? How do we make money? How do we spend money, all of these things come together, we need to define who the customer is. And so if the whole executive team is having that discussion, they’re looking at the whole rather than just their little part. And that was really useful.

F-L-O-A-T: Team

It also started a lot of fights in the executive team, which it turns out was what they really needed. It started a lot of fights, and eventually got them to the point of teamwork. And I want to tell you a little bit about that.

The fight started when the CPO and the CMO disagreed on the target market definition on the ICP – the ideal customer profile. The CPO wanted to narrow it down to a small group of customers that they had proven that they could be really successful with they were the customers who love them and would stay with them through thick and thin. And but the CMO was like well, but I need to generate X number of leads. And I need a bigger pool to pull from in order to and I can show you all the math, here’s my spreadsheet. And what I really want is to hire two more BDRs. And my spreadsheet says we will make millions if I can hire two more BDRs.

But the CPO was like, Well, sure we’ll get more leads. But we won’t sign the deals or even if we do we’ll lose them eventually because they won’t be happy because the product doesn’t do all the things that everybody wants. It does the things that These people want. So they were having this back and forth argument. And there was also an argument between the services team and the sales team. The services team wanted to, of course, manage to billable hours and utilization. And that’s how they were, that’s how they demonstrated their success. The sales team wanted to give away services for free as part of the deal. Because customers perceived weaknesses in the product and the sales team, they wanted to say, we’ll we’ll do that for you. And that product guys were like, I’m not putting that on the roadmap. So the sales team turned to services and said, we’ll do it for you. But the services team would fight that.

And then there was a fight between the CPO and the services team as well about whether we should standardize the product or allow a lot of customization. The CPO actually wanted to shrink the services team and stop using them for things and just focus on the ICP that they could serve with the out of the box product. So back and forth, and back and forth, everybody’s got a different way of solving the problem of a business model that’s not quite working.

It was it was getting hairy at that point. This is when they were starting to think about layoffs. Because they were they discovered that lots of their deals were unprofitable. In the end, lots of their customers were not making money for them. They were burning cash too fast. This was not last year, but the year before when VCs were kind of pulling back. And they wanted to extend their runway as long as they could, until conditions changed, or they reached profitability. And so they were desperate to figure something out. And nobody could agree on what that something would be.

It got to the point where they agreed on a set of OKRs. Four of them at some point. Everybody around the room set nodded and said yes, these are the four. And then the CTO went to his team wrote the four on the whiteboard and crossed out to them and said, You will just focus on these two. And the only reason I know that is because of “No-No” who was in the room at the time. It got to the point where two of the executives on the same day went to the CEO and said it’s him or me. About each other, exactly, right. Not not about the CEO, but it said said You know, I’m the CPO, he’s the I won’t mention who the other executive was. And they each said about the other you got to fire him.

The CEO to his credit, did not fire either of them and did not take did not, did not give into that did not take the bait there. What he did was he, I’ll tell you what he did in a second. There, what I was seeing was short lived alignment. They did act collaborative. When they were in the room, they were on good behavior with me. But they were very judgmental when they were a part. The challenge came from the CEO, he he said, Look, we we can’t keep acting like this. We need to grow up and be a real company. And you two, not just you two, you whole team, you need to do your jobs. And I’m not firing anybody. This is the team we have. This is the team you will work with. If you cannot do that, there’s the door. And they all stayed. And and they worked really hard together to bridge that gap.

Now I think I mentioned that they were spread geographically between the US and Europe. And I think that was an obstacle for them. The CEO, even though this was during a cash tight time period, brought them together for several days in Europe, in person and sat them down and didn’t give them a big agenda. He just said, we need to work this out. We need to work this out being a team. And the tool they used was that they actually workshops together a set of what they call Team One: Operating Principles. Team One is a nickname some people use for the executive team. And the idea here behind that calling a Team One is your primary team, Chief of marketing is not marketing. Your primary team is the executive team. Your primary team, CTO is not the technology team. It is the executive team. Yes, you have two teams but your team one is this team around the roundtable.

And they they workshop together with a little bit of input from me a series of principles and I want to share my favorite one, which is that they agreed that they would all seek understanding. We will seek first to understand, understand and then to be understood, by actively listening and demonstrating genuine curiosity about one another’s perspectives, thereby enriching our knowledge and fostering more effective communication. I would have wordsmith that and said decisions somewhere in there too. But, but this is what they came up with. And they had a dozen of these principles that they workshopped over the course of a couple of days.

This was my favorite one. It’s the one that their CPO when I talked to him last week before this, before putting together these slides that he called out as the one that made the most difference. Because being apart and having your particular hat to where marketing or sales, or whatever it is. You’re not always sympathetic with the other person, you’re listening to them. And you’re like, compiling your counter arguments as you’re talking. Right? But this reverses that and says, All right, I’m here actually to listen, in order to understand from a place of genuine curiosity. Curiosity of okay, I hear what you’re saying, tell me why. Not, I hear what you’re saying but tell me, why? It’s got to be more like, genuinely want to know not, that’s the stupidest thing I ever heard. This was the this was the key thing that got them out of fighting, and into teamwork, as a team.

How Did It End?

And like I said, there, they haven’t gone IPO or reached a billion dollar valuation or any other huge milestone. But they have, they have gotten back on plan, they have a stable team with a couple of two, two new members. They have, once again, got their team, their customers loyalty, this system is stable, and they are collaborating as an executive team to figure out having gone. They were like going like this. And then they went like this. And now they’re going like this, again, they want to go like this, but at least they’re going like this.

When I talked to the CPO, he said, I think it’s a success story of aligning on what really matters and working together, even if we haven’t solved all the problems yet. And I thought that that was the right, that was the right summary.

So that’s FLOATING. And that’s how they got to floating back up from the depths, if you will, I’ll also give you just a quick summary of the tools that they use in case those are interesting and you want to take a picture of this. OKRs were really useful for them in driving focus and identifying where they were misaligned. Once they started to focus participative decision making unlocked their ability to move forward with getting more focus and alignment.

Reviewing the OKRs every two weeks, created the embarrassment I mean, visibility for them to actually measure progress and decide when they were not on the right track. Working on the business holistically as a team one from the outside in from the customer’s point of view in and agreeing on their operating principles. I don’t know if they really needed to, like reduce them to a set of operating principles, except that once you’ve written them down, you can point at them, which is really helpful as a reminder, but they needed to come they needed that bit of empathy, that bit of seeking understanding that they really needed that key operating principle.

Aligned: Stakeholder Management for Product Leaders by Bruce McCarthy and Melissa Appel

That’s my summary. And here’s my advertisement. I am writing my second book, my first book was on was on Product Roadmaps. And I spoke about it here back in 2018, I think. At when the book was relatively new. This book is about Alignment. It’s about stakeholder management across different functions. It’s primarily pointed at product leaders or people who want to be product leaders. But honestly, it’s generally applicable to anybody in business who needs to get stuff done through other people, which is I think, most of us.

And so it’s called Aligned. It’s called getting aligned, the book is done. We’re doing the layout and design right now. And the publisher tells me if we stay on schedule, it will be shipping from Amazon by May. This is the preorder QR code if you want to try that out. It would really help me if you didn’t wait to order it until it comes out but it pre ordered it instead that’ll give me a sales boost on day one when it comes out. So if you’re thinking about buying it, now’s the time. And so I’ll just ask you for that favor. And that’s my talk.

Q&A

Mark Littlewood

Thank you. Right, questions?

Audience Member

I have two. Yeah. First one is what happened to “No-No” in the end? And the second one is if you’re struggling with the OKR and you, you know, you cannot move forward, how do you go to unstuck that and continue with that?

Bruce McCarthy

Your second question was how do you unstick it unstick OKRs. So OKRs is one of those things that is really easy to get, right? There’s only two parts, the objectives and the KRs. It’s just really hard to master. And what I have found is that people need to learn by doing with OKRs. And by doing I’m gonna go back to the Ninnu’s talk. They I mean, failing. They they you saw they failed miserably the first time out. And that’s not at all unusual. Usually it takes turning that wheel a number of times. And the faster you turn it, the faster you learn. It’s the only antidote I wish I could say, you need to hire the right coach. But the right coach will not micromanage you. He will let you fail and learn from that. That’s my answer. Okay. Other questions?

How do you unstick OKRs? Okay, so the first question is what happened to “No-no”, he’s still there. They kept him. He went from tah to hmm and he’s decided he’s he’s actually turned down two or three offers, including one from me to stay at the company. So that I thought that was a good sign when “No-No” decided to stay.

Mark Littlewood

Question from the side. I don’t know what…

Audience Member

First of all, Bruce, thank you. I’m spot on to our problems. So kudos for for this great speech. I have two questions as well. First one is you show before that you introduced one decider. How to do to ensure that you do it, that is one decider didn’t mean micromanaging the end and right decisions? And the second question is How big would ideally this be this team of listeners? So the one decider was listening to?

Bruce McCarthy

Yeah, okay. So, how do you keep having one decider from becoming a micromanager and by micromanager, I think I heard dictator in there somewhere. And the second part of the question was, who should be among the people consulted the you get the input from?

So the real trick in the participant, a participative method is to decide who’s the decider for which kinds of decisions. Now on the executive team? Where are we focused? It makes kind of sense that the CEO would be the decider and the other people who inform that person would be the other members of the executive team. But let’s take that model somewhere else. Let’s take it to engineering, the or product development. We’ve got product managers, we’ve got designers, we’ve got engineers, we’ve got testers, we’ve got maybe data scientists, too. We’ve got a bunch of people who decides what? Well, first, I would say you got to agree who decides what, but probably there are pretty easy traditional domains for different sorts of decisions. The product manager is probably going to decide what problems are we going to solve, and how do we prioritize them. The engineers are probably going to decide, technically, what’s going to be our approach for solving that list of problems. The designers are probably going to decide, how do we make it easy for the customers to use this stuff, once we have built it.

So none of it is mysterious, usually, who owns which decisions is being clear about it. And then if you’ve got to, you’ve got to maybe have a tiebreaker sort of scenario to there’s this whole framework if you’re really into it called the DACI framework. It’s like RACI but for decisions. So D-A-C-I look it up if you’re interested. We describe it in the book. And it has a role for each of the of those people the the DACI stands for driver, that’s the decider. There’s also an approver in case people really hate your decision there’s somebody to appeal to and so on. Is it like? I don’t know raid? Actually, it’s that’s a process right? And DACI is more like the rolls. But I totally I think you’re on the right track. Yeah. Right.

Mark Littlewood

So up two you say, John. The two by two matrix you say management consultants. I know you’re gonna go with you then Chris. Just because you mentioned.

Audience Member

Thanks, amazing speech. From my perspective, I was interesting of hearing what role safety had on gelling that team work together.

Bruce McCarthy

Yeah, she asked what role safety meaning psychological safety, right? People were saying to me, including “No-No”, every day, this is not a safe environment. I don’t feel okay about disagreeing. I think there was a piece of that going on when the CTO agreed to four OKRs and then told his team to only work on two. Because he didn’t feel that it was safe or okay to disagree with the group, when he actually rightly were felt that they were trying to take on too many things. Some people viewed that as some sort of trickery or betrayal, but you could see where the behavior came from.

Ironically, that particular CTO, the reason he’s no longer there is he also created a very unsafe environment in the engineering team. He was a yeller. And so there was a lot of lack of safety going on. When the CMO and the CPO were arguing about the ICP. The CMO, I could see instantly was afraid for his job, because he didn’t think he could make the numbers with a smaller pool, with a smaller market to pull from. But he didn’t exactly say that. And nobody brought that out, even though that was clearly the subtext. The where things started to get a little safer, was actually when the CFO came. And at the beginning of one of our OKR, sessions, gave an hour and a half overview and Q&A on the economics of their business. Everything, all the different moving parts of the business. And they all started instead of pointing at each other and arguing with each other. They were all kind of looking at the numbers together. Oh, okay, I see how this works. And, oh, why is that number so big, and so on. And they were starting to collaborate on stuff that they didn’t all know. Or feel individual ownership of? That kind of turned off the fear, temporarily. And then, it was it was a start. So your intuition is 100%, right.

Mark Littlewood

Yeah, and I’ve got one here. Anyone else? Keep your hands up? Because we’d like to cycle the mics as I hope you’ll have worked out after two days. Chris?

Audience Member

Bruce. Yeah, thanks very much for for your presentation. This felt like deja vu for my business. Absolutely. I mean, we implemented OKRs, probably about five, six years ago. And it was revolutionary in sort of getting the focus into the team, including rejigging the management team, creating some culture fundamentals, which I suppose is your team one operating principles. But the one thing that I found inhibited the alignment piece that required us to go back and rethink about was looking at each division and getting clear on the diagram, and the mission of each division, right. And then defining the overarching areas of accountability for each division. That for me, kind of was the game changer in getting the alignment within the team. So that everyone understood that, okay, cool, we had these OKRs, we had these, you know, results we were chasing, but who could actually influence them. And it wasn’t just about like, Okay, this is the high level, you know, top number for the company. But actually, these are the teams that carry the responsibility and the accountability. And that was a huge improvement in alignment.

And then I would go further to say that we made it a point of getting collaboration within each sub team. So with our OKR structure, we do a two day Breakaway, we do a first day of discussing the high level objectives. And then we have a break for a week to allow each team to go back and collaborate on how there’s going to be executed down on the ground. And then we come back as a management team a week later and discuss and say this is how we’re going to bring it to life through the collaboration with the team, which I have found has been hugely helpful in ensuring that there is success. And we recently rolled it out to our dev team because we use an outsource company and we were seeing that fragmentation of Chinese walls. Oh, so client’s supplier relationship. And the way we broke that wall down was to get the dev team in the room with everyone in business and go, here’s why we’re doing certain things instead of treating people like mushrooms, just getting them actually part of the decision making process. So just wanted to share appreciation for helping you live relive my nightmare moments over the last 10 years but then just supplementing with my own experience.

Bruce McCarthy

Really quick story. I hope you guys won’t mind me sharing. But I was with a client yesterday, and one of their executive team members said, I, I expect certain things and they’re not happening and I don’t understand. And a list of certain things gave me a deja vu moment because this, this book that I’ve written on Alignment is like a Patrick Lencioni book like Five Dysfunctions of a Team. It’s a story, as well as a framework. And I had written almost exactly the same words coming out of the mouth of one of the executives in my novel. And as as this, this was, as you were saying, these things, I was like, well, there really are some common themes, right? In the world of software, in the world of tech in any company, as it evolves.

And just to sort of echo what you were saying, a part, part of the OKRs program that I didn’t talk about, was that cascading down to the teams that are accountable for the things that contribute to the company’s top level OKRs. We did that too. And we did that with that same week gap, so that the top level OKRs for the company were given as an input from the executive team, then the other teams went and created their OKRs as an answer. And then we had a reconciliation session between them, just as you say, the engineers and the business people coming together to talk about the push and the pull between the two of them. And then we had a final version of the OKRs that came out of that. And I think that kind of alignment, again, across the whole org, not just within the executive team is absolutely necessary for OKRs to work.

Mark Littlewood

Thank you. Got one last one here.

Audience Member

Thank you. My question is you’re okay, you’ve got “No-No” and you’ve got yourself, and you’ve got the leadership team. And the leadership team goes to, This doesn’t work. And you were trying to give them umbrellas, or to get them to understand the umbrellas and you’re not seeing a bus. At which point, do you and which quarter, how do you influence them to try something else?

Bruce McCarthy

Right.

Audience Member

What was your when? Where did that happen?

Bruce McCarthy

What was really interesting from this particular team, because you’re absolutely right about umbrellas versus buses. They gave me the in their first set of OKRs. They gave me seven umbrellas. And then they nearly got hit by a bus. The the outages nearly cost them a lot of customers, right. But your question was how do I influence change? Well, my approach as a coach is usually to whisper in different people’s ears, is to talk to everybody one on one, listen to them, understand them and provide a nudge. Because my my way of thinking is that people learn by doing and they need to try stuff. And they’re not going to try it if it’s at least not with a with a genuine curiosity, unless it’s sort of their idea. So I try to put the ideas in such a way that they become their ideas, and then let them try it and let them learn from things that don’t work too. This particular team, I discovered, after the first turning of the wheel, they don’t work that way. They wanted someone to tell them what to do. They wanted the kind of coach that’s closer to a drill instructor. After after they pick the seven OKRs and they failed, I kind of said, you know, in a very polite way that I told you so. And they said no way, way, way you didn’t tell us we had to have three or two or one. You said it was best practice. You should have said you can have three. And so I began to take a more directive approach with them. Or I should say, I began as a coach to take the participative approach. I listened to them all and then I told them what to do. And that worked with these guys. Including telling the CEO he had to be the decider. I didn’t, what I didn’t say was I said the team told him he needed to be the decider. I was behind the team saying you have to tell him that he’s decider.

Audience Member

And how about “No-No”, because “No-No”, was that to help as well originally?

Bruce McCarthy

That’s right. But he he wasn’t he didn’t feel safe, really stepping out. He worked for one of those executives. And so he knew that he was perceived as loyal to that person, and he didn’t trust that person. So he would tell me the things that he was witnessing that were going on. On the night, that’s where I got all the chatter and the inside intel. And then I would come to the executive team and say, This is what I am hearing and this is what you need to do. Does that make sense? So I had to, I had to go against my nature but what I really wanted to do was to give the team what they needed. And and it was really gratifying just last week to hear from the CPO that he felt like, in my mind, mission accomplished, that they were on a better path as a team. I guess we’re done.

Bruce McCarthy

Founder, Product Culture

Bruce founded Product Culture to help communicate the key principles underlying consistently successful product-focused organizations.

He and his team help companies like NewStore, Camunda, hyperexponential, Socure, and Toast achieve their product visions through Advising, Accelerator programs, and the Product Culture Community. Bruce is a serial entrepreneur and team leader. He literally wrote the book on roadmapping: Product Roadmaps Relaunched: How to Set Direction While Embracing Uncertainty. His next book, Aligned: Stakeholder Management for Product Leaders is expected summer 2024.

His previous talks at BoS Conference have been instrumental in helping our attendees unblock some of the significant challenges that all companies face as they grow. You can watch them here.

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.