Rita McGrath is a longtime professor at Columbia Business School and one of the world’s top experts on innovation and growth. She is also one of the most regularly published authors in the Harvard Business Review.

This BoS USA 2019 talk gives company leaders food for thought with questions such as do you incorporate diverse perspectives in decisions? Do you empower small, agile teams? Are there resources available for little bets? And does your organization reward truth-telling?

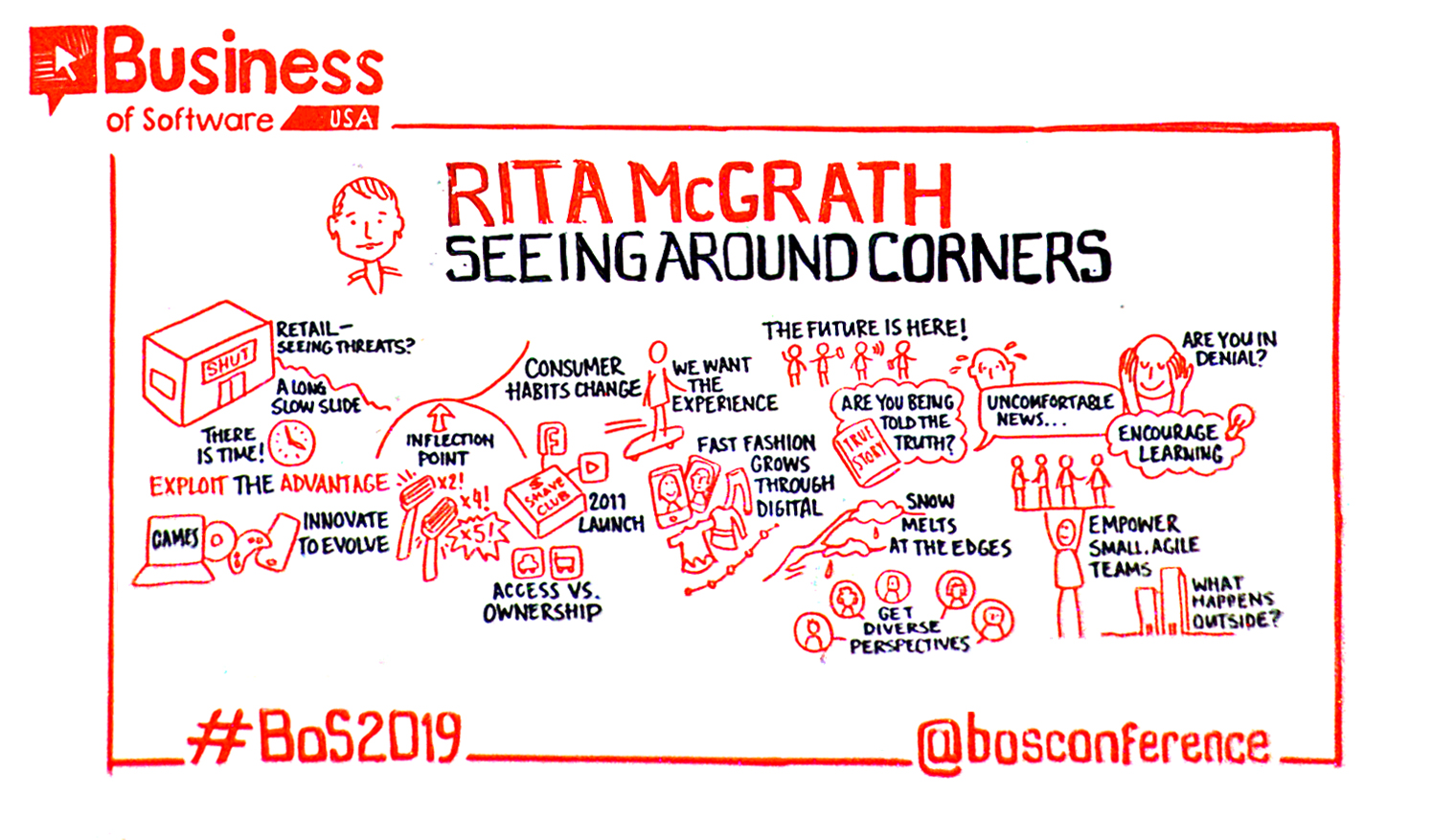

Find Rita’s talk video, slides, transcript, sketchnote, and more from Rita below.

Find out more about BoS

Get details about our next conference, subscribe to our newsletter, and watch more of the great BoS Talks you hear so much about.

Video

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.

Slides

Transcript

So, there is a story behind that music. Which is it; is the inflection point represented by the transition from conventional music stored on stuff that we actually buy, to music in all kinds of formats that we rent or lease? So, I thought it would make a poetic beginning to this topic.

So, thank you for hanging in here. I’ve been here since I guess the first night of night one and really just, I always learn so much when I come here because it’s not a world I normally live in. So,, what I’d like to share with you for the next little bit is some work from the new book which I’m delighted you all have got a copy of so I’ll give you a little overview and a taster and some practical things that you can do yourself.

So, the book is about strategic inflection points. Now what, may you ask, is a strategic inflection point. It’s a moment or a sequence of events which eventually cause the assumptions you are making about your business, to become separate from the reality of your business. And the reason this happens is any business is created at a particular point in history when certain things are possible, and certain things are not. So, as a business begins to discover its business model, its product market fit it begins to enjoy the recipe for success or, more specifically, its leaders do. You start to become dependent on a set of metrics – routines things that are taken for granted – as the route to success and as you get better and better at running your business, you learn what metrics to push and which things to move faster and which things to step back on, and what is going to lead you to Nirvana.

An inflection point changes those realities. It represents a 10x change or a significant change in some parameter that you thought explained what would lead to success in your business. And so, the easiest way to understand this is if you think of conventional retail. Conventional retail was all about real estate you know and every single metric in that area had to do with how well you use that real estate. So how did this store do compared to other stores? How much did you move over a certain limited period of time? How well did you turn your inventory and so on, you get the idea.

Seeing it coming

So, you grow up in this business and most of us will spend. A lot of our lives in a business that’s sort of running and what happens is something comes along, in this case the Internet, and starts to invalidate those assumptions. So, that connects to the seeing it coming. Part of an inflection point but as the book makes clear – I hope – just seeing it coming isn’t enough. It’s not enough to see that it’s an opportunity it’s not enough to see that it could take your business to new heights. You have to be able to then mobilize the organization to follow it. So, the book really has three themes:

- How do you spot an inflection point and we’ll talk about that a fair bit today.

- How do you decide what to do about it which is not always easy.

- How do you bring the organization with you?

So, I thought to put this in context I’d start off with an interview of someone who saw an inflection point coming and proved spectacularly unable to do anything about it.

“So, there’s an audio recording of the now former Sears CEO Eddie Lampert addressing employees at the company’s headquarters in Illinois after filing for bankruptcy which happened yesterday. Lampert rarely speaks publicly. Here’s part of his reflection. When Sears and Kmart merged in 2005.

I believe back then that massive change was coming to retail and with massive change from a lot of opportunity. If the world of retail was going to be stable, it would have been much more difficult to create something different. There’d be no Amazon just a larger Walmart and they would not have been the opportunity for Sears to break from the pack once again and change the face of retailing like it always had in the past. As we all know we haven’t capitalized on this opportunity the way I would have liked. Instead of growth and investment we have faced retrenchment and restructuring.

Lampert also said and I quote “We have to figure out how to take what we have learned and fight another day.” Let’s remember the bankruptcy filing is for reorganization.”

So, Eddie Lampert bought into Sears I think in 2005. He’s owned this entity for a long long time. Saw the inflection point coming, ‘Oh my God the Internet’s going to change things’. Now here’s the other interesting thing about inflection points. They feel when they are upon you as though they happened overnight; as though they came out of nowhere. And yet if you look at them they take a long time and it’s a bit like the old quote from Ernest Hemingway’s book The Sun Also Rises, when one character asks another well how did you go bankrupt and this character responds ‘Oh well gradually, and then suddenly’.

And that’s kind of how inflection points are. So here’s the thing, Eddie Lambert’s no dummy. I mean he was at one point being lauded as you know the natural follow on to Warren Buffett and he saw the inflection point very clearly. And yet the piece that involved bringing the organization along just never really happened and there’s a lot of reasons for that. But you can sort of see both in stock price and in revenue this went on for years. Years. A long slow decline. And so that’s the second piece of my argument. So, the first piece is inflection points change the assumptions underlying your business. And if we’re so invested in the business of today, we can easily miss them. But the second point is the good news is you have time.

You have time

These things don’t emerge overnight and come to destroy you from nowhere, there there’s always early warnings. Now the other interesting thing about Eddie Lampert story is there were other players in the areas served by a company like Sears namely Home Depot, Lowe’s Sears was a big provider to home hobbyists. And both of those companies figured out how to serve customers better how to keep stock better how to keep people well coming into the stores. I mean they’d had their ups and downs but by and large their story has been a growth story over the same time that Sears story has been a decline story.

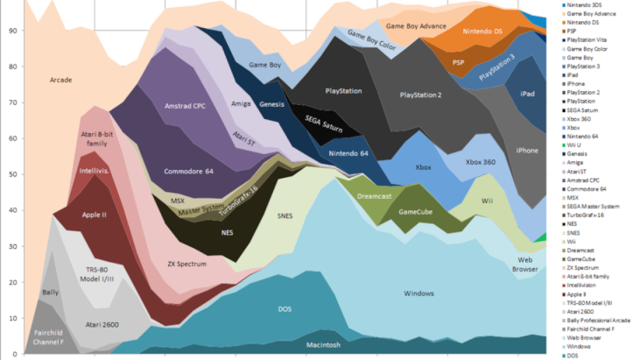

And I think that’s another property of inflection points; when you do them right, they can take your business to new heights, when you get them wrong, they can be kind of devastating. Now all this is set against a backdrop and the backdrop is something I wrote about in my previous book which I’ve spoken about at BoS before which is this notion of shorter and shorter competitive advantages. So, in strategy theory right for years we had this idea of this fabulous thing called a sustainable competitive advantage. And the idea was you found an attractive position in an attractive industry – we used to teach this stuff – and then you would throw up entry barriers like crazy and protect that position for a long time. And so, all of your internal gearing a lot of what you did as a company manager was you exploited that period of advantage. That was your job. And my argument has been for some time that’s great if you can find one. In the world most of us live in competitive advantages come and go. And so, this chart is just a chart from the gaming business, and it reflects market share position in various gaming platforms over time. Many of you will know this industry better than me.

But you know in the beginning what did we have. We had arcade games. You had to go to a physical place to throw money at this refrigerator sized machine. It was only open when the opening hours were there. The games were mechanical right. The game and the intelligence that played the game were built together. There was no sort of software there. Then we had the introduction of software and now you could actually have games and devices separate. That was a big advance. Then you had sort of games that could be in different form factors: games you could take with you. Games that could be played on general purpose devices. You started to see different kinds of games – instead of just combat games you had ‘Civilization’ and ‘The Sims’ and games like that where you were creating different worlds. Today where do we play games? On your phone. In virtual reality. Now we’re starting to see A.R. and VR enabled games it’s super cool. There’s this application where you can have like a Tyrannosaurus rex coming into your conference room it’s pretty astonishing what they can do now.

What matters here is the pattern. And here is the core thesis. If you’re trying to run a company for the long run if this is what’s going on outside your organization, you need to have an equal amount of the innovation and variety inside your organization. Because that’s the only way that you’re going to respond and keep up. The other thing I’d draw your attention to is the pattern of the lifecycle of a competitive advantage.

- There’s a period when it gets created and grows.

- There’s a period when you get to exploit it.

- And then there’s a period of erosion. When it goes away.

And I believe most executives I work with – and I work with a lot of them – are completely baffled by anything other than the period of exploitation. Now you’re all kind of entrepreneurs, you’re in the software world so you’re more familiar with the full phases but a lot of your clients won’t be. And I think that’s one of the things that you’re going to have to get smart about which is teaching them how to get up that innovation curve so that whatever you’re selling can become part of the businesses they want to exploit going into the future.

Strategic inflection points

So, I think that’s kind of an introduction to an inflection point. Now let’s talk about some specific ones that I think are particularly germane to a whole class of new kinds of disruptive competitors. And this is the kind of dramatic shifts that have been created in the assumptions by companies like Google and YouTube and Amazon Web Services and Facebook.

So, let’s take a specific historical example and I’d like you to imagine that you are an executive at Procter and Gamble. Specifically, in the Gillette division, these are the razor people. And Gillette has had this amazing business model it’s lasted them literally for decades. We invest in RND, that allows us to create better technology, that allows us to then use our armies of salespeople and massive global distribution to get the word out. We support all of it by a massive mass market advertising. This is awesome. This is a machine. It’s very hard to copy that model for others. Now what were the products like. Well King Gillette, the founder of the company, invented the world’s first safety razor. Which you could actually use at home without having to hone it on a strop. And this was great, and they were better and better and better razors and then come 1990 they had this idea. They RND people said hey you know we could put two blades on this stem. And they dithered and they said OK we’re going to launch it we’re going to be aggressive it’s going to be called the sensor razor. And they had this cartoon advertising the sensor razor which was awesome it had it had like the first blade would come along and like pick the hair up from your face and the second blade would come along and slice it off. It was awesome. Amazing. Two blades better than one blade right. This is amazing. OK. So that serves them well for about 10 years. The sensor razors top of its game and then they’re like OK what’s the next thing? How do we get more profit? Remember their model is RND>better product>higher prices>global distribution but that’s the model and we are executing that model really really well. So, they invent the …

Mach 3! Yes! 3 blades! 3 blades – better than two blades of course. And gentlemen I don’t know if you remember this but if you bought a Mach 3 razor you were cool enough to sit in the cockpit of a fighter jet. That’s what the advertising was it was like the best a man can get. OK. This goes on very nicely for five or six years. They’re do really well. And then: strategy calamity Schick gets bought by Edgware and they rush to market with the world’s first Four bladed Razor.

You can only imagine the consternation, the wailing, the ‘Oh my God what do we do’ in the Gillette boardroom, because I mean you’ve spent literally billions of dollars teaching consumers two blades better than one blade, three blades better than two and now a competitor has the world’s first four bladed razor. I mean what is one to do?

Well of course the first thing they decide to do is unleash the lawyers. They tie everybody up in court and then they rush to market with the world’s first Five bladed razor: The Fusion. OK so first of all you can kind of ask where is this all going right there comes a point at which you kind of Clayton Christensen’s famous words sort of overshot the market, what will we have little tractors running across? I mean I don’t know. So, the thing I want you to think about here though is this is what is on the mind of the people over at Gillette. This is what they’re worried about. They’re worried about Schick. They’re worried about five bladed razors. They’re worried about what’s the next innovation we have to have so we can keep our prices up. Meanwhile, not in the garage but certainly in a living room or two. There’s a guy called Mike Dubin and his co-founder who found a company called Dollar Shave Club and Dollar Shave Club was essentially born out of opportunism. His partner had secured some. Not too fantastic but not too awful either Korean razors and wanted to know how to unload them. So, a real entrepreneurial story.

Dubin the founder in the face of the company has this vision. He says wait a minute. Using all of these new technologies so I can use Amazon Web Services to build my tech stack. I can use kind of programmers on demand to build out whatever I need to do. I can use you know flexible temporary resources, but more importantly I can use YouTube, and Facebook, to get my message out to millions of people. And I can use this sort of budding frustration of many men with the shaving experience not the shaving experience so much as the shaving maintenance experience – you have to go to the drugstore right and have the Shavers locked up the razors locked up in this Shaver fortress, and you have to like go locate a retail person who’s willing to like undo the thing for you. So, the person comes up with the jailer keys, you know, and you feel like a criminal it’s terrible. Plus, you can forget them you could run out and Gillette is not stupid, these are very expensive razors the margins on these things are great. So, there’s a lot of negatives.

Dubin basically puts together a YouTube video which is targeted mostly at a younger demographic and the whole if you haven’t seen it, yet you must go see it it’s really hilarious. But spends like I don’t know $25,000 on this thing, puts it up on YouTube becomes a viral sensation, opens for business, and its concept is very simple direct to consumer you know who needs these guys why do you need to go retail? We are dollar shave club; we will send you these blades each one a dollar plus some shipping you’ll get them every month. No running out. No going to the razor fortress. None of this nonsense. And it a pretty decent price. So direct to consumer.

Now this was never possible before in the world Gillette lived in. This is not a possible thing. You can’t go direct to consumer. First of all, your direct customers are all going to be ticked off at you. And secondly, it’s just too hard. What Dubin does is he works his way around television, he works his way all this stuff is no longer necessary. Now think about it prior to YouTube prior to Facebook and so forth if you wanted to get a message to a billion people you had to be Metro Goldwyn Mayer you had to own a movie studio. You had to have billions of dollars’ worth of assets. Once these inflection points have happened and this digitally enabled ecosystem exists that’s no longer necessary. So, you’re new here are the guys at Gillette, you’re worried about Shick you’re worried about. You know you’re not thinking about some guy in a proverbial garage putting a funny video on YouTube that goes viral.

Do you see what I’m getting at here? It is so easy. If you’re an incumbent to get blindsided now that’s obviously an opportunity for the people doing the blindsiding which I gather most of your companies would be on the side of. So, I think it goes both ways. So, what happens. Dollar Shave Club launches in 2011. They formed in 2010. They launched lightning fast 2011. And by 2015 Gillette had lost something like 16% of its market share. They went from 70% of the U.S. market all the way through to down to 59%. And they’re fighting like crazy to try to keep that. And so, what do you do as an incumbent? Well, Gillette of course launches the Gillette Shave Club. Duh! We’ve got the Gillette Shave Club and they’re kind of going to market with ‘the blades you love, at the convenience you want’ kind of thing. But I think the loss has been real. And I think it’s just interesting to tell that story in the light of what’s on the minds of the various competitors in this sector.

Software enables access to assets, not ownership of assets

So, one of the things software has done it’s enabled – on a mass scale never seen before – access to assets rather than ownership of assets. And that changes the strategy conversation. Our assumptions about what we have to own to be competitive are totally different today than they were before. And I’m not saying that’s good or bad. What I’m saying is it changes the game. And that’s really what the book’s about it’s about how do you get ahead of some of those changes that can be so disruptive. And one of the biggest sources of blind spots I see, is that we define ourselves in many cases as part of an industry.

When I was a kid when I was starting in the field all the cool kids were doing industry analysis. I mean that’s what you did if you were a cool kid in strategy, you looked at order of entry statistics and R and D intensity in the top three players, and all that stuff everybody was looking at industry. Those of us studying innovation God forbid, we were sort of huddled in the corner for warmth. I mean there was not very much patience given to us back in those days. And what’s happened in the meantime is the concept of innovation in the concept of strategy have really come together. So that you can’t really today talk about the one much without talking about the other at the same time. And I think increasingly what we’re seeing is digital is now part of that conversation. You almost can’t talk about innovation without talking about software or digital in some way.

But industry, as a construct, I think is a big blind spot. So, here’s a study that was done by the Wall Street Journal. It was done in 2014 and they were interested in understanding what had happened to American households spending patterns since the advent of the first true smartphones. And what they found was spending was way down on items like home furnishings and apparel and cars. Two biggest categories of spending up by double digits during that time period which don’t forget encompass the Great Recession. So that’s even saying more Internet to the home and cellular communications. So people were literally saying I’m not going to buy a pair of jeans this year I’m going to spend the money on my cell phone minutes. So, if you’re a jean maker, if you’re in a parallel maker and you’re busy benchmarking yourself against other apparel makers as good strategy practice would suggest you’re missing the point completely. What you’re seeing is people are not spending on you, because they’re spending on these other categories. And that suggested to me we need a different concept than ‘industry’.

We need to stop thinking about competition being confined to industries because just not helpful in a world full of these inflection points. Instead what we want to think of is what are the jobs customers want to be done – I’m sure you’re familiar with this idea it was created by Clayton Christensen. What are the jobs customers want to be done? What are the alternative ways those jobs could get done? And what part of resources exists to enable that job to get done? And that’s the way I think of something I call a competitive arena.

What do customers buy will they buy ball bearings and roll but what do they want. They want the experience of flying on a skateboard. That’s what they’re that’s what they want that’s the outcome. To go back to Theresa’s discussion from the other day. So, let’s take an example near and dear to many of our hearts. Let’s think about clothing. How many of you have teenagers or you all were at one point teenagers, so what’s the job clothing does for teenagers?

Popularity.

Self-expression.

What tribe am I part of what tribe or am I not part of.

It’s a lot of communication clothing does for teenagers right now. My mother’s definition of quality in clothing would be a little different. My mother’s definition would have been clothing that lasted through multiple wash cycles, and it held its form, and it didn’t stain, and it didn’t wrinkle, and it was sturdy, and it was probably purchased it like J.C. Penney’s that would be my mother’s definition of quality in clothing. Your friendly local teenager These happened to be Japanese teenagers because they just seem like such an extreme expression of the breed, but it’s all about communication. What are teenagers doing these days. They’re all hermetically connected to these devices. And beginning in around the year 2000. What were they doing with those devices? Texting, but not just text right… Yes selfies. And that started way back when in the early days of text messaging I mean you could start to take pictures on your phone even then, there was a Washington Post story that I referred to in the book which talked about teenagers shopping in the year 2007 already on their phones comparing with their friends should they buy this/should they buy that.

So, we’ve established that now we’ve got sort of Instagram and we’re now in this very interesting moment where it’s almost existential. If a tree falls in the forest and nobody caught it on Instagram did it happen? Talk to teenagers it’s scary sometimes. But you know your goal for clothing a lot of times is you want to look good for that perfect selfie. And the clothing as far as you’re concerned could self-destruct at that point. It’s like the modern day version of Mission Impossible right. This message will self-destruct after you’ve done what you need to do with it. Well what does that tell us about quality and clothing?

What are we after are we after the same blue outfit event after event? Now we’re after clothing that looks fantastic for long enough to take the perfect selfie and then we want to move on. I would argue that whole trend towards fast fashion, which is an environmental disaster and I think that we may be on the brink of a backlash but we’ve been living with it now for almost 20 years that what teens want is this fast inexpensive it doesn’t have to last season to season, I wear it a few times and I’m done kind of clothing. This is actually produced tells us an interesting little secondary flurries because thrift shops and charity shops are now enjoying a resurgence in popularity because what teens are realizing is ‘wow you can get it really cheap there wear it a few times and you can bring it back and they’ll take it!’ Amazing. It’s great. Now this is one of the trends. It’s not the only one but it’s certainly one of the trends that’s contributed to the decline of traditional parts department stores. Now again existing model based on the constraints that were possible of what made that industry what it was at the time we have for clothing seasons a year. We send our designs over to Asia at the beginning of every one of those seasons, they make the clothes, they come back by ship, we sell what we can at high prices at the beginning of the season, when whatever hasn’t sold we discount or we get rid of. That’s the model. And instead what you’re seeing is the fast fashion retailers; what are they doing. Continuous flow.

Think of Zara. You like a black skirt in Zara you better buy it today because it may not be there tomorrow and there’s no guarantee you’re ever going to see it again. It’s a much more continuous flow fast kind of kind of activity. Very very difficult for a traditional retailer to deal with because it’s a different totally different business operations model.

Now as I said there’s always a winner in these inflection points Somebody always wins this particular case, I’m going to pick on Ross Stores. Ross Stores is a store here in the U.S. they’re kind of like a treasure hunt, they have this wild assortment of brand name and off brand and all kinds of cool things but they have done fabulously well over the last 20 years or so. Oh, interestingly Ross Stores CEO happens to be a woman was the only woman named to Forbes list of the hundred most innovative people in the United States. So, I will let that be what it is but a very interesting question there anyway. But they clearly did very very well with this trend. So, I’m not saying these are predictive. I’m saying if you’re looking out for those weak signals you can see them a lot more. So what I’d like to do with the bit of time that remains to me I’d like to take you to an exercise that we know that I’ve got into the book which is how do you prepare yourself to see these weak signals? What are some practices you could use to get yourself ready to do that. So that’s where the little sheet that was just handed out comes in. And what I’m going to suggest is as I’m going through this maybe make some notes for yourself on what do you do. And if we have time we’ll have you compare notes with a colleague if not necessarily in this format maybe at lunch or some other time.

So, these are some practices that my research suggests are helpful in helping CEOs/ leaders/senior executive teams actually see what’s going. And the inspiration for this comes from Andy Grove’s original work in the 90s on strategic inflection points which was obviously a huge influence on me. And interestingly not a whole lot has been done on that since his seminal book Only the Paranoid Survive and what he said in that book was if you are in the midst of winter and you want to know where spring is making itself felt you have to go to the periphery, because that’s where the snow is most exposed. So, the way I reframe that is:

Snow melts from the edges.

You have to get out to the edges of your organization to see what’s really going on. So, the people talking to customers talking to competitors seeing what’s actually happening in the marketplace. Snow doesn’t kind of present itself in an organized manner at your corporate conference room table so you can make a net present value informed decision about it. It doesn’t do that. It comes out there from the edges. So, these are eight practices that I’ve found are kind of associated with being able to get out to the edges.

So, the first one really has to do with how you use your personal time. Do you budget some personal time, regularly, to personally get out to the edges and see what’s going on with your company, your customers, what’s happening with those exchanges? Now here’s the problem. The organization will try to hide the truth from you. They don’t mean it out of bad intent but it will happen especially the more senior you get, and the more power you have, the harder it is to find out what the hell is going on. So, here’s an example of this: the gap. The gap had made a commitment in 2015 to try to give their retail workers more reliable hours right. So rather than sort of work hours fluctuating up and down every week let’s see if we can add some predictability into the mix. And they were really struggling with this. And so, the New York Times wanted to know why is this so hard?

And so, they went and interviewed some Gap store managers. And the first thing they said was Oh well it’s corporate. You know corporate will tell us we’ve got a huge nationwide promotion on skinny jeans happening on Thursday and so all the skinny jeans need to be up front and centre to be in conformity with national promotion standards, and the store managers like to have everybody running around moving the skinny jeans to where they needed to be. “Corporate”, big problem.

But the second one I found even more interesting. Executive visits. As one reported, and you can see it here on the slide, I must’ve had two or three shifts working extra hours to get ready for an executive visit. So, let that sink in a minute. Is the store that executive is visiting the store you and I see when we go shopping at the gap? No. It’s got fresh light bulbs everything’s gorgeous. They probably splurged a little on extra scent maybe, and some chocolates by their cash register, I don’t know what they do. But the point is the store we’re seeing is a fiction. It is not the normal experience. Your people will do this too, because it is human, and it is natural. If you have company coming over of course you tidy up the living room. But if you really want to see what’s real, you have to get beyond that. And a lot of times you have to remember the organization is not necessarily your friend when it comes to finding out what’s really going on. And the bigger your organization gets, the harder it is to cut through that. So that’s I think the first question to ask yourself. Do I regularly make time? Am I sure that I’m really seeing what’s going on or am I conveniently listening to what I’m being told by people who honestly would rather I didn’t hear the bad news? Good question to ask yourself.

Second question has to do with diversity. And this is not diversity in the politically correct sense but it’s diversity in a really important sense. So, here’s an interesting bit of research that was done by my colleague Cathy Phillips and she studies diversity. And one of the difficulties with real life is that it is almost impossible to attribute causality to outcomes. You can make horrific, stupid, self-serving, idiotic decisions and have a good outcome. And you can make well crafted, thought through, carefully argued, very good decisions and still have a bad outcome right. So, there is this disconnect between causality and what actually happens that we struggle with in real life.

Actual output:Perceived output

In a laboratory on the other hand we can construct experimental conditions so that you know whether a group did well or did badly – which is what Cathy did. So, here’s the bottom line to her findings. Homogenous groups meaning people that all thought the same way, and in her studies it was mostly groups of men of similar ages and socio-economic backgrounds, they felt great about the work that they’d done when they were put into an experimental situation. It was fantastic. We all spoke the same language. We got very quickly to a decision premise. We finished the work efficiently. It was fantastic. In other words, homogenous groups feel great about the work that they do. However, their work output is actually not very good on the experimental standard that Kathy set up.

Diverse groups. So, you introduce a few women, you introduce a few people from other cultures, you sort of mix it up a little. Oh my God that was so hard. Like I had to really struggle to even understand what that person was saying, it took us forever to come to a conclusion. It was just really really effortful. But the work output was much better. So, here’s the super ironic thing I’d encourage all of you in this room to think about homogenous groups perform worse on creative problem solving tasks, but they feel great about it. Diverse groups perform far better on problem creative problem solving tests, but it feels awful. It’s so hard. It’s so miserable. Take that and use it right because homogenous groups that all think the same way that all come from the same place that all the frames of reference miss things.

So here’s one of my all-time favourite examples of this I was actually in a conference something like this being presented with sort of new product development pitches and there was this incredibly lovely team of people young people from Ivy League schools all over New York City and their project was a thing that’s now called Link NYC. And the idea was they were going to take all these payphones all over New York and replace them with these cool kiosks. And the kiosks were going to be amazing. They were going to have unlimited internet access in place you could charge your phone you get like local directions and it was going to be there was like a very utilitarian great replacement for the pay phone. And people were going to use these things the way that that team thought they would. They’d look up the latest trendy restaurant, and they’d ask for directions to the best tourist facilities, and they’d get that kind of thing. So they’d do a citywide rollout of this program. Which is a mistake to begin with – you want to test a little before you do that. But anyway, they did the city where they roll up and within 24 hours what do we have. We have homeless people setting up living rooms around these kiosks and watching YouTube for 12 – 18 hours a day. They’ve got no place else to be, why not.

We’ve got we’ve got people watching unlimited porn in Times Square. All these things happening when you introduce unfettered unlimited access to the streets of the city of New York. And my argument is not that they were a stupid team, or this was a bad idea. My argument was there was nobody on that team who actually understands what happens on the streets of the city of New York to alert them to what the possible unintended consequences could be. Big embarrassment. They had to withdraw. They had to shut down all the Internet functionality and they’re at the point now where they’re even talking about taking away the phone charging thing which they’re debating. But I think it’s the kind of mistake you can make when you don’t have diverse perspectives weighing in and decision on your team.

Third and this has been touched a lot on in this conference so I won’t spend too much time on it, but if as a leader you can give small teams the context, the objectives – as was said earlier in the week, the metrics, the clarity you can get away from top down decision making committees you really can be much more crisp. This particular slide is taken from Patty McCord deck. You mean she’s a legend in Silicon Valley. Patty McCord was the H.R. person responsible for setting up the Netflix Culture and part of her task in doing that part of her output. In doing that task was she put together this like hundred and thirty three page PowerPoint deck laying out all the principles of what she thought Netflix Culture should be. And it’s still available on the Internet. It’s one of the most downloaded Power Points of all time. If you haven’t seen it, it is totally worth getting it if you just search Netflix Culture. Patty McCord H.R. Dec you’ll find it and it’s just full of wisdom. I mean real wisdom about what kind of company do we want to have. And she put this together in the very very early days at Netflix, so this wasn’t like by the time they’d succeeded this was the forward looking view of what their culture should be. And this was one I thought was good. So, the question for you is do I empower small agile teams? Do I let them make those kinds of type 2 decisions where we’re not betting the ranch? Or you know and I top down control telling them what to do? The more you can let them try things out the more experimentation you’ll have and the more you’ll get insight from what’s out there at the edges.

Do I have resources for little bets? This this is an example one of my favourites from Adobe. Adobe has this program many of you will know of it called the Kickbox. And if you are an employee at Adobe and it could be anybody, it doesn’t have to be just the scientists or the RND team. You can request a kickbox and if you answer a few simple questions they’ll give one to you. Inside the kick box which is a red box are some instructions. It’s like a game almost you beat the box by going through a certain set of steps. It’s also got some card for Starbucks, a candy bar because you know all innovation drives on thrives on caffeine and sugar, but the most important thing in it is a $1000 gift card. And you are not required to get justification for how you use that. It’s an experiment. You use it. The only requirement is that you report back what you learned into a common database so that others can learn from what you tried. And you know they’ve given out over a thousand of these things over the time. And so that’s what a million bucks and then CEO gets asked all the time 2what are doing giving ordinary employees a thousand dollars?’ they said ‘look, relative to what we spend on RND it’s nothing. And look at the variety of experiments we’re able to fund by doing that. Basically, it’s pushing experimentation capability right down to the level of the ordinary person. Also, it’s teaching them what innovation is all about.’ Remember we have this life cycle. Most of the people in a large organization like Adobe have never built something from scratch. They don’t know what that’s like. So, this is simultaneously training plus empowering people at the edge to kind of do things.

You might know this guy. This is Steve Blank a very good friend of mine and Alex’s and he’s got a phrase I think all of us should take to heart which is

There are no answers in the building.

There are no answers in the building. If you want to know what’s happening with technologies, with customers, with you know where things are heavy, you get out of the building. And that’s an encouragement to not drown in email and spend all day in meetings and stay up all night working on you know hacking together something internal. It’s that external view. Get out of the building when in your week when in your month do you make the time to get out of the building? Part of that is what I do when I come to BoS, which is I love listening for what’s new. I love listening for the different perspectives and whoa I never thought about that before. That’s one of the reasons I come it’s my way of getting out of the building. It’s been my entire life with megalithic corporations and learn nothing. So, I like to come here.

Then we’ve talked a little bit about incentives. I think the question you all need to ask yourself especially if you’re in a leadership position is ‘have I built a set of incentives in my company that make it OK for people to bring me uncomfortable news?’. We’ve talked previously about psychological safety, how important that is. This is a supplement to that that to that idea that that’s one of the most important things you need to do. And just by way of sort of illustrating this, I thought this was interesting, So Kraft Heinz – you all know them iconic American company – gets bought up by a Brazilian hedge fund called 3G and 3Gs whole thing has cost. 3Gs operating model is we. Find a fat and happy dumb company where we think we can load it up with debt, take it off the public markets, make it more efficient, repay the debt, we take our money. Life is good. That’s their model and they’ve been quite successful they bought Anheuser-Busch and they bought a bunch of other firms and for a while it worked very well with them. They bought Kraft then they merged Kraft and Heinz cost cost cost cost cost. OK so you work in that company and you are dealing with something called zero based budgeting. No slack. And you’d like to take a plane flight perhaps to go explore what what’s happening in the Minneapolis market with one of our condiment brands are you going to feel comfortable asking for that resource? Get on the plane and go do that? No. You’re being asked every day. Zero base. What do you absolutely positively need at a minimal level to make this thing work? There’s no slack in the system. And we all know innovation is not predictable it requires a certain amount of slack. These are brands that require reinvention. These are not stable steady brands that are in good shape. They are brands that are into erosion. And in fact, it was last March I think it was that Kraft Heinz announced a $15 billion write down of the goodwill represented by the Kraft and Oscar Meyer brands alone.

Now as evidence of this, Glassdoor – you’ll know Glassdoor their employees can sort of point, rant and raves and praise and whatever and they ask these questions and asked the employees of a couple of different companies how many of you would recommend this place as a great place for friends or family to work? At Kraft Heinz: 29% said they would recommend the company – and I would bet most of those work in procurement. Less than a third of all the people working in that company that reported were willing to say this is a great place to work, come join us. So, what kind of culture do they have. Is that going to be the kind of culture where uncomfortable news about the greening increasing irrelevance of our brands or the need to reinvest or you need to do anything is going to be there. I would say not.

Denial

So, you need to think about incentives because you know it’s hard enough for people to tell you bad news right. It’s hard enough to say something went wrong without actually you know rewarding people that don’t do that. Then there’s denial. Denial or old friend denial. This said this is picture of Alan Mulally many of you will know him as the former CEO which turned Ford around. Very interesting story but one of the things is Alan tells the story. He says well you know his first day at Ford he pulls into the executive parking garage at the Ford Motor Company, looks around. And beholds no Ford branded cars in the executive parking lot. It’s not a good sign right. So, Alan is a very famous management system which if you’re interested in it, I can go into. But basically, it involves everybody in the decision making body of the company the sort of senior leadership getting together once a week, and they have their plan for the week, and the plan elements are all coded. Green is good I’m on track. Yellow is I’m on track or I’m not on track but I kind of know what to do about it. Red is I’ve got a problem and I don’t know what to do about it.

Now before the first of these meetings, which by the way all the Ford executives resisted, Alan’s response to that is ‘Oh OK, that’s OK’. He’s always smiling and if he says, ‘that’s OK’, once you get to know him a little bit the little hairs on the back of your neck should go like that because it’s not OK. “It’s OK”. “You can’t be a member of the management team at the Ford Motor Company if you don’t come to my meeting, but it doesn’t mean you’re a bad person”. So you get the idea.

So, a couple of days before the first of these meetings he gets the news that Ford is on track to lose something like $16.8 billion close to $17 billion. Comes into the meeting, everybody’s got their numbers spread, and none of them want to be there. And they have people that do stuff or they don’t do their own performance reviews. But anyway, he forces them to do it. It’s all there. All Green. Everything’s green. And he’s kind of looking at his executive team saying, ‘is it our plan to lose $17 billion because if it is, we’re right on track’. And he said something I think every executive should have on their desk somewhere. He said:

You can’t manage a secret

If we can get the data out and we can talk about it. We can do something about it but if we don’t know where the problems are. They’re never going to come to the surface. They’re going to be a lot worse when they do. And so finally a couple of these meetings go by. And finally, Mark Fields who became CEO of Ford after Alan retired said all right all right, I think I’ve got one of those red things you’re always going on about I’m red on Edge. Now Edge was a small SUV that Ford was counting on, and it had been a bit hyped to the dealers, hyped to the press. This was going to be the symbol of the new Ford. I mean it was just everything was piled on this launch and Fields has just said. It’s not going to go forward on schedule. He’s just admitted to a huge issue, and the whole room goes completely quiet. All heads are kind of turning to Alan like what is this guy going to do because he’s new. They don’t know him yet right. So, what does he do? He stands up. Applauds great transparency, Mark. Anybody got any ideas? And they go around the table and sure enough like somebody understood how to deal with the dealers. Somebody else had a couple of engineers that could be lent to the effort. Another person knew what the next problem was going to be after they solved this problem. Within about I don’t know four minutes they had probably 60 to 70% of the solution already framed up already from that quickly that quickly because they were working together. The expertise in the room. So, I think this idea of let’s not be in denial. Let’s get those problems out there so we can work them is a super important one especially as you grow as you get bigger it gets harder.

So, I asked Elena and Alex and I spent a fair amount of time with him. And so, I said to him well what was it like after that meeting? He said Oh my God it was a rainbow in there. It was terrific. He said but in a way it was great. If it had genuinely all been green, and we were on plan and we were on track to lose $17 billion that would have been so much worse. Which I think is a very interesting, very positive attitude.

Last thing.

There’s a wonderful science fiction writer named William Gibson who is famous for saying the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed yet. So, here’s my question to you: Where do you go to sort of talk to the future that’s here, but not everybody knows about it yet?

So, here’s the thing. Let’s say you want to understand for your business what the 20 year olds of 10 years from now are going to be like. Let’s say that was something you had an interest in. Well guess what – I can guarantee you this with statistical certainty every single 20 year old of ten years from now is 10 years old today. And you could go have a conversation with them. So, here’s a 10 year old. Her name is. Trinity. And she’s addicted to these loom bend things you know because it’s a popular thing. I’ve become convinced by the way that there’s a subculture for everything on this planet. Whatever it is there’s a group that is into it. But loom bands are her sort of thing. She lives in a single parent household in England. And her thing is she comes home from school and she goes on her device and she watches YouTube videos of other people doing these loom band things and then she does things of her own and she posts her own videos and it’s a whole community and they learn from each other. Well here’s the problem. The Wi-Fi had gone out at her house. So instead of using Wi-Fi she was actually burning up network bandwidth doing these videos and so her poor dad gets hit with a £1400 phone bill at the end of the month. This was not good. Just a horrible situation. I think eventually they got it resolved but it made the papers it was that dramatic. So, let’s think a little bit though. Like what could we learn about Trinity and people like her that might be relevant for our long range planning? What are some of the things we’d have to we think might be true?

Is she going to ever expect not to be connected?

How’s she going to learn?

Do you think she’s going to have to go to a physical place like our old gaming devices and learn there? No. It’s going to be peer to peer learning. It’s going to be on time on demand. Anytime she wants it. That’s the kind of information she’s going to be seeking out. I’m not making predictions here but what I’m saying is if you wanted to open your mind to what that future person is going to be like you could start to have some hypotheses built. You could start to say here’s some ideas here’s a point of view that I might have about how this could happen.

So, here’s the summary. You have the sheet in front of you. My encouragement to you would be to take a little time before you get back into the everyday post BoS craziness and make a little note to yourself. But what are some things you could do to fill in some of those boxes and maybe you don’t have them all – great exercise to do with your team those of you that have teams that come great exercise to do with your peers. If any of you were in a peer group look at Tiger 21 or something. Terrific exercise to do there. So that’s the summary.

- Do I make sure I have direct contact with the ‘edges?’

- Do I incorporate diverse perspectives in my decisions?

- Do I empower small, agile teams?

- Do I make resources available for little bets?

- Do I regularly get out of the building?

- Does my organization reward truth-telling?

- Have I checked that I am not in denial?

- Do I deliberately seek out aspects of the future that are here today?

So, let me wrap up with the following. As I said I think strategy innovation and digital are coming together in a way that is unprecedented at least in my experience. And it’s really going to be very central to what you folks are doing with your businesses and going forward. Last thought is strategy isn’t what it was. I think we’ve really changed our view. Inflection points take time. Eddie Lambert in 2005 saw the inflection point that was coming for retail. Had he been able to bring the organization to a good place he might have been where Lowe’s or Home Depot is today. But they’re not. Being aware. I think that first that seeing part is the first step to seeing around corners effectively.

So, thank you very much.

Sketchnote

Find out more about BoS

Get details about our next conference, subscribe to our newsletter, and watch more of the great BoS Talks you hear so much about.

Rita McGrath

Rita McGrath is a longtime professor at Columbia Business School and one of the world’s top experts on innovation and growth. She is also one of the most regularly published authors in the Harvard Business Review.

Her work and ideas help CEOs and senior executives chart a pathway to success in today’s rapidly changing and volatile environments. McGrath is highly valued for her rare ability to connect research to business problems and in 2016 received the “Theory to Practice” award at the Vienna Strategy Forum.

Recognized as one of the top 10 management thinkers by global management award Thinkers50 in 2015 and 2013, McGrath also received the award for outstanding achievement in the Strategy category. McGrath has also been inducted into the Strategic Management Society “Fellows” in recognition of her impact on the field. This will be the second time she takes part in Business of Software Conference USA – she discussed how entrepreneurial business owners benefit from an understanding of the new strategy playbook back in 2013.

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.