John Snyder started Grapeshot in a small office overlooking King’s Parade, right at the heart of the Cambridge tech cluster. While Cambridge is well known for the quality of its technology, many companies have struggled to turn their technology advantage into global commercial success. John was determined to do both in the global adtech market, not one that is traditionally associated with deep Cambridge tech.

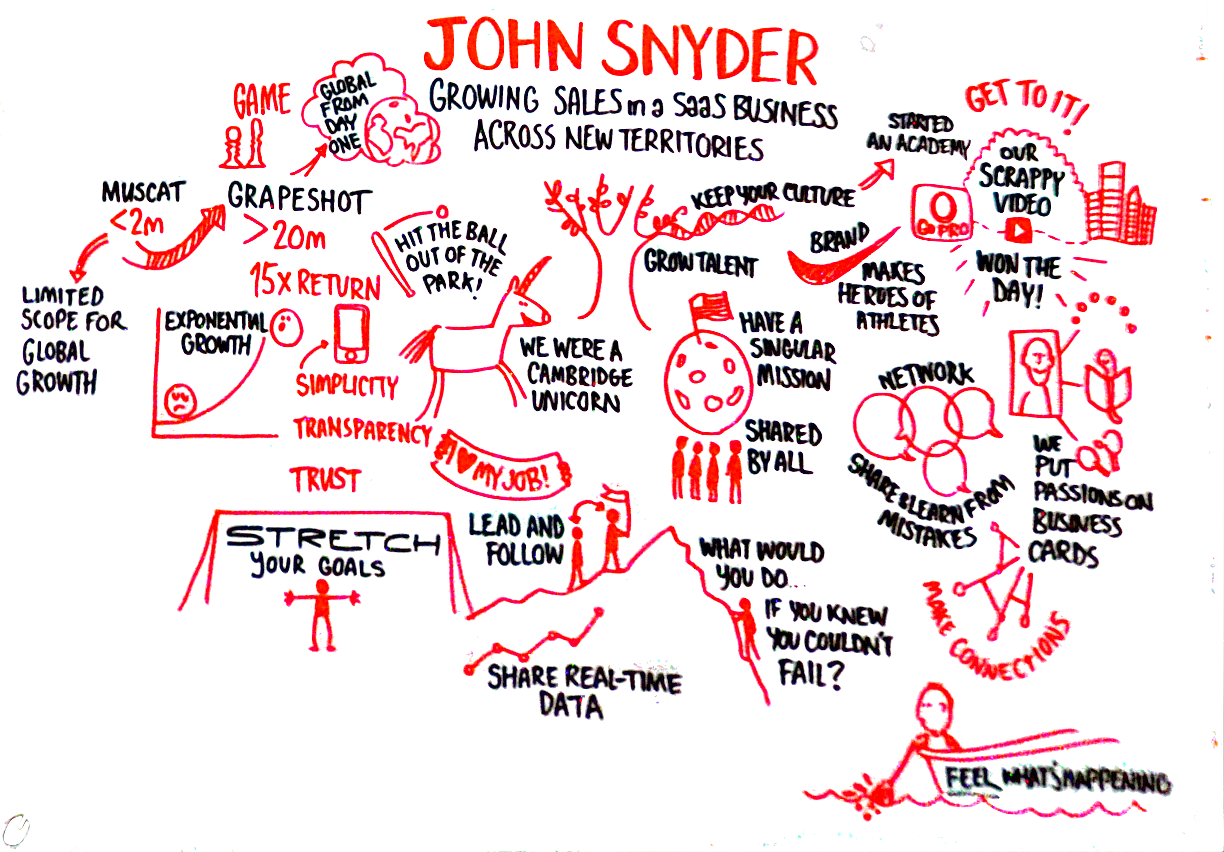

In this talk from BoS Europe 2019, John talks about how he set about educating himself by learning from others and why he decided that his business had to have a global vision from the outset. He describes entering new markets with a relatively limited supply of capital which meant every new move could have been very costly. Ultimately, much of the success of the business was down to maintaining a clear company culture whilst operating across several continents and territories amidst different social cultures.

The company was acquired by Oracle Corporation in May 2018.

Slides

Sketchnote

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.

Transcript

John Snyder

So Mark asked me what I’d like to have playing as I entered, and I said ‘play Comfortably Numb by Pink Floyd.’ So he showed me the YouTube video and it was five minutes long. I thought ‘Great. I can kick off my speech talking about being comfortably numb.’ David Gilmore is fantastic as a guitarist. And we were in Rome the other day, and there’s a fantastic Pink Floyd exhibition. When you go to Rome, don’t go and look at the temples, go and pay homage to Pink Floyd.

So business for me, is never about money. We say in Cambridge, people have ideas to change the world. It’s not about profit. It’s not about revenue. And most of us don’t make profit for a very long time. We use other people’s money to try and grow revenue, but it’s a game. And what I love about growing businesses is the sequence. How you play that game. The steps you take, in what order.

So I have two businesses to talk about. One is Muscat. So we’ll call that A. And I set that up fresh out of university here at Cambridge, teamed up with a very clever guy. And this took five years to go from start to exit. Five years in your 20s feels a very long time. But Grapeshot was really inspired by what I did between those two companies. And I want to share some of those thoughts. And for Grapeshot, it was actually 13 years; it was nine years of commercial activity where I actually got a pay packet in my pocket. But they were different journeys. They were different games of chess, and I want to share some of the aspects of that with you.

Now, it was great to have Dame Shirley on stage and talking about that wisdom of age. But when you’re 26, you don’t know anything. You’re so naive, you just charged ahead, like a bull in a china shop. You just have that passion, conviction. In fact, my problem because I had a degree from here and I went to try and get a job when I had a young daughter. Noone gave me a job because they thought I wouldn’t stick around because I had a degree. There I was applying to Cambridge Water for a job just so I could get a salary. So I could look after my wife and daughter. So age 26 I set up Muscat.

And after that journey of five years, I ended up helping set up Library House where Mark worked. I’m one of the founding members of something called Cambridge Angels. I joined the RDA (Regional Development Agency), we pumped money into about 400 companies, through smart awards, everything to do with the public square. So I was basically unpaid for 10 years. And that’s what retirement is, by the way, it’s being busy, but no one pays you.

And then as I came out of that, my co founder of Muscat said, “Look, I’ve written something new, it’s fresh. You’re going to help me again.” I thought, “I really do like playing those games of chess.” So I went in for it. And I was 39 then, when I was 30 I was like, “I’m tired. I’m knackered.” So 39 is really interesting, you know, going into your 40s. You have a wisdom – not that wise – but you really have a different frame. And I think it’s that extra age and experience that really helped the way I grew Grapeshot.

Now I am competitive and I love winning Monopoly. And the best feeling is landing on go. And Grapeshot clearly, quite a few of us did land on go. Muscat, sad to say there are only two of us who are millionaires. Some of the staff paid off their mortgages. And rather like Dame Shirley, I was always keen to have every member of staff have share options from day one. Muscat, we had a 10% quota. In Grapeshot, I was constrained to 15% because of the investors that came on board, but I was pleased. I think I total up 27 millionaires. So there’s much more sharing of wealth across the team. But as I said, it’s not really about the money.

Now, we only raised probably between 1 and 2 million at Muscat, not much capital. And in today’s world, we raised over 20 million US dollars with Grapeshot. But we had a trickle-trickle-trickle-trickle. Reed Hoffman – who set up LinkedIn – when he saw Grapeshot, when we pitched to him there was only five people talking to him. So we sais “Let’s come see you in your office.” And he really did want to invest. He wanted to invest six months before packing us up to Sequoia. My co-founder, who’s a very clever mathematician – in his 60s at the time – said “John no, you can’t do that. That’s fireworks. You know, that’s all the American venture capitalists.” So we purposely took very little money, we’d dribble in 2 million, or 3 million or 5 million, we never went for the big bucks. And that was just one of those values, we weren’t going to shoot to the sky, we’re going to work hard and do our jobs well.

But we hit the ball out of the park, so I’d say to my team. In Muscat, I only returned 10 times the money to the investors. And in Grapeshots, we did it 15 times. So that’s pretty good in terms of return. And they often say, entrepreneurs are a one trick wonder. For me, it’s like, if you know how to do one O-Level or GCSE, you kind of know how to pass many of them. I think it’s the same with building businesses, I think there are some very generic things you have to focus on. And that’s kind of what I want to share.

So the alchemy, it’s the same processes. But remember, I did them differently between Company 1 and Company 2. So, we sold out under 20 million. I can’t talk about the deal. But in the press, they say it’s between 3 and 400 million. So I failed. Because at our last management team, Offsite, we had the little unicorns on our forehead, and some of the people in the company said “We do not like this sense that it’s a financial output. That’s not why we come to work.” But all entrepreneurs know to actually come out of Cambridge with a unicorn, where you’re worth over a billion dollars is actually something to be proud of.

I was probably about 18 months away from that, we were growing 180% year on year revenue, profitable at the time that we got acquired. So the lead investor did well. And he was a dragon. And the dragon is where one investment returns the whole size of the funds. And he tried to charm me but he said, “Actually, John, Grapeshot’s one better, because you’re a Double Dragon. The money we put into you paid back our fund once over, twice over.”

So in terms of capital efficiency, in terms of training people to be on a journey and play a great game of chess. Now people can recycle. In fact, I think it was on this stage 15 years ago, I heard someone say, “Cambridge is a low risk place to do high risk things.” And so the ability to recycle that capital, I’ve already invested in other companies myself, there’s lots of experience, lots of team members, that’s perhaps a better thing for the economy, rather than just being the unicorn.

Now, I haven’t shown you the last year of sales, that’s going up to April 17. But you get the sense, it’s accelerating. And it’s very strange to be in a company where you grow 40% year on year, then 60%, then 80%, then 120%, and then 180% trebling revenues, basically doubling your staff year by year. And so that exponential curve is something we spoke about, probably two or three years before we actually got acquired, where we’re really thinking about: what is exponential? And how do you plan for it? How do you seize opportunities? You’ve probably heard this dictum that if you stride one meter, exponentially, it’s very different to linear. One meter, 30 times linear is 30 meters, but exponentially, you go 26 times around the world. It’s that giddy feeling of just going very, very fast and getting faster.

The rule of the thumb is: expect to be surprised, then plan accordingly. And I feel that as an investor in early stage startups, people present plans, “This is the market, this is the technologies, this is the product.” I’m like, “No, no, no, I’m more interested in how you think. And to what extent you know how to take on surprises.” Because a lot of my journey in business is about being surprised, surprised by what a client says. In fact, where Grapeshot pivoted in its journey was fundamentally not my idea, it was the idea of one of my customers. And I think it’s really important that you have an organization that knows how to deal with change, and huge exponential growth.

Now, when we sat after the deal in a bar in London, my chairman said “Johnny did three things really well. And one of them was how you went to the US.” Because normally, if you go to the US, you get a headhunter and you hire a really senior sales director who’s already got a really good Rolodex. I didn’t. I took the most junior people in my London office, someone fresh out of uni. Now we take Matt (bottom middle), he was interviewed by the sales director and turned down in London, saying he hasn’t got industry experience. Client Services Director, she interviewed him, “No no. He doesn’t have the experience. We want people who already have the Rolodex. He doesn’t have it.” I thought, “Well, he’s got an American passport and I have a plan to go to the US.” So I met with him over a coffee, and I hired him. I thought “This guy’s got attitude. He’s right. Got the right DNA.” So contrary to my managers, I took him on. I said, “Right, six months in London, you go to New York.”

So that motley crew started in New York. Top left is the nephew of our chairman. I interviewed him. I put him in a show. And basically, I told him to go around and meet people. And as I went around the show, people said, “Oh, I’ve just met your colleague from Grapeshot. Thomas, what do you think of him?” And he basically showed he could do the stuff. So I took him on.

That motley crew started a business. Matt himself oversaw $20 million revenue a year with four people in the US market. Now, that’s someone who grew in our culture. It wasn’t something I hired. But I think the most important step is that I took the most junior people who already understood our culture, and they transplanted it into New York. It’s a very important lesson when you think about culture.

So to my surprise, I’m having dinner with the dean of the Judge Business School – where I sometimes do talks – and I had John Halfpenny, one of the founders of ARM to my left and Jonathan Milner from ABCam. And we’re all talking as entrepreneurs. And the Deans really interested in getting us involved in the program. I talked to him and I said, “I’ve got a problem with culture, I think I’m growing so fast, I can’t keep it in the bottle. What do I do? My DNA is changing with all these recruits.” And he was like, “Oh, culture. That’s soft stuff.” He’s interested in the business cases, and to a penny, every single person around the table rounded on him. They literally said, “No, no, at ARM, right in the early days, we interview for culture, the culture is the backbone.”

So when you’re going exponential, what is the spine that keeps you? What’s the spine to the business that’s giving you that structure, that allows you to transport yourself to New York, or to Singapore, or to Shanghai. So culture is absolutely vital. If there’s one thing you invest in, not your product, not your customers, not your sales. It is who you are. It’s absolutely vital for success.

Now, Harrison Smith – who’s the guy in the photo – I had the privilege of hearing him at a big event. I think it was either Intel or Dell. And they said, “Oh, hang around John, we’ve got some speakers.” And Harrison said NASA was amazing, because it had a mission. Man on the Moon. How many of us in our businesses have clarity on that mission? That desired end state? Why we are here is to go to the moon. And he described how the janitor was involved in that mission. Everyone in the team was on fire. They came to work for a reason. And it was awesome, actually, as I left I ended up asking “What does it sound like on the moon?” It was a stupid question because all the breathing apparatus is very noisy indeed but it was amazing because as I left, I had a palm tree and the moon and Harrison right there. And I thought “He has walked on that moon.” I mean, how audacious was that? In the 60s and 70s and 80s?

So culture is everything. And you learn this as you talk to other people. How do you put your finger on it? I thought I would play a really bad quality video of someone who’s quite well known. But I think he’s got important words to say and there’s subtitles there.

Steve Jobs

To me, marketing’s about values. This is a very complicated world. It’s a very noisy world. And we’re not going to get a chance to get people to remember much about us. No company is. And so we have to be really clear on what we want them to know about us. Now Apple, fortunately, is one of the half a dozen best brands in the whole world, right up there with Nike, Disney, Coke, Sony. It is one of the greats of the greats. Not just in this country but all around the globe. But even a great brand needs investment and caring if it’s going to retain its relevance and vitality and the Apple brand has clearly suffered from neglect in this area in the last few years. And we need to bring it back.

The way to do that is not to talk about speeds and feeds. It’s not to talk about Bits and megahertz. It’s not to talk about why we’re better than Windows. The dairy industry tried for 20 years to convince you that milk was good for you – it’s a lie – but they tried anyway. And the sales were going like this. And then they tried “Got milk?” And the sales have gone like this. It’s a method that focuses on the absence of the product.

But the best example of all, one of the greatest jobs of marketing the universe has ever seen as Nike. Remember, Nike sells a commodity, they sell shoes. And yet, when you think of Nike, you feel something different than a shoe company. In their ads, as you know, they don’t ever talk about the products they don’t ever tell you about their air soles and why they’re better than Reeboks air soles. What does Nike do in their advertising? They honour great athletes, and they honour great athletics. That’s who they are. That’s what they are about.

Apple spent a fortune on advertising. You’d never know it. Never know. So when I got here, Apple just fired their agency. We’re doing a competition with 23 agencies, four years from now we’ll pick one. And we blew that up. And we hired Chiat Day. The ad agency that I was fortunate to work with years ago, we created some award winning work, including the commercial voted the best ad ever made in 1984 by advertising professionals. And we started working about eight weeks ago.

And the question we asked was, our customers want to know, “Who is apple? And what is it that we stand for? Where do we fit in this world?” And what we’re about isn’t making boxes for people to get their jobs done. Although we do that well. We do that better than almost anybody in some cases. But Apple’s about something more than that. Apple at the core, its core value, is that we believe that people with passion can change the world for the better. That’s what we believe. And we have the opportunity to work with people like that, we’ve had an opportunity work with people like you with software developers, with customers who have done it

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.

John Snyder

I’m going to stop it there. But you can see the theme. The theme is really: what is the value in your company? You talk about product, you talk about sales, we solve this little problem. But what do you stand for? What is that binding spinal element in your business that’s going to sustain that exponential growth? Its values, we’ve already heard the importance of values in the previous talks.

So it was strange, because I didn’t know what values we had at Grapeshot, we just started, we were just having a few customers, perhaps we’re about 15-20 people. And I hired a marketing director, as a consultant to come in, and do a 360 of our staff and our customers and ask, “What do you think about Grapeshot?” And it was really surprising, because people had a lot to say about who we were as suppliers, the different staff that they met, and our own staff. So we took people from the senior team and some of the junior people and essentially pulled together a working group, and they had to come out and define our culture. So it’s very strange that the CEO wasn’t saying “This is my vision. This is my stuff.” It was actually accumulated out of proper market research.

They came through with three values, the values have stood for all the years, those 10 years, and I even know post acquisition, they still continue within the unit.

So simplicity. You’ve probably got the idea that I really appreciate what Steve Jobs and Apple have done. But can you imagine creating a phone with one button? I remember my wife once asked, “How do I do this? Where’s the button? There’s only one and now there’s none.” The point is there’s simplicity. And Steve Jobs really worked hard to get that simple element to the market. And Grapeshot’s success was evident in the early days; we went onto a platform, and someone said, “Wow, you must do so much marketing. You’re the most used app on this platform.” I said, “No No, no, we don’t do any marketing.” It was the simplicity of the product.

So sometimes people put bells and whistles in, they make it complicated, more friction. If you can go for the simple thing, and get that to market early, that’s when your product starts to get more traction. But for us simplicity was: make it simple when you explain it to colleagues, make it simple when you talk to your customers. So simplicity, we weren’t being special and being complicated and creating that friction barrier with colleagues or customers. So simplicity is very important.

Transparency, I’d share all the numbers with everyone. We’d get onstage and I’d have anyone in the company talking about their line of work in the business. So we’d all learn from each other. And we’d talking about problems and issues as much as success. And I remember one guy who was coming to join us for a job. And we said, “Why don’t you come to our little company off site, we have like three or four hours of talks. And then we go for beers.” He was a lovely chap called Francisco. And I remember seeing him at the bar, he says, “I love this company!” And he hadn’t even joined on his first day of payroll, but he got the culture. And that was the key thing. It’s very, very important.

Now, after Muscat, I got involved in someone else’s idea to set up the club, it’s called Full Moon. And I don’t know whether you know, but in the industrial revolution, there was a time in Birmingham, when the moon was out, people could navigate the messy streets full of sewage, so they could go and meet. And this was the kind of industrial revolution at its heart, really sharing lots of ideas and thinking and creating new innovations. So we did that in Cambridge, we got CEOs together. And it was great to have someone who had floated Domino on the market, public company, mixing with a four or five person startup. I think I’ve just seen someone in the audience that was one of those early startups. And essentially, we had cross-sharing of knowledge and information.

I think what’s really staggering is I’ve learned more from other people’s mistakes than my own. We all learn from mistakes, it’s the best way to learn. So have a culture where everyone makes mistakes! It is so vital to make mistakes. That’s how we learn as humans, that’s how we learn walking up the stairs and everything. But you’ve got to have the culture that really embraces how we learn from it, and how we move on and step forwards. So I encourage you to talk to other people and find out all their mistakes, because there’s a much faster way to do it, than doing all the mistakes yourself. So networking is very valuable. A lot of people say: “Why do I go to these events? What ROI did I get?” Whereas I find if I look back three or four years, it’s that chance meeting with that person over there or that cross bridge to that one over there. And I think my company history is built on serendipity. And that’s that surprise of the exponential curve that certain things happen. And active networking and knowing how to network is a vital ingredient.

But I think the most important thing we had was the word “Faith.” Now faith is quite a strong word these days, whether you’re religious or atheist or the like, but faith in people is a very fundamental concept. And I’ve been surprised by some of the management theory where I suppose we were doing this, but we’ve really tried to trust people. So you’re not telling people what to do. And I found in Muscat I was also a commander in chief, telling people what to do, and they’re almost queuing for decisions to be made. Whereas in grapeshot it was that sense of “No, no, we’re very clear about the mission man on the moon, we know the desired end state, you have the flexibility to go out and do it your way. We’re here to support.”

So the manager style is to support and give really strong resources. If you’re interested in this stuff, look up a guy called Larry Yatch. He ran a management off site session for us and he was in charge of a Navy SEALs team. And you’re thinking: the military, it was all command and control? Well, it isn’t. He’s basically taking someone into Kuwait. They’ve got a 50% mortality forecast on their team. And they have to go in and basically take over an oil rig. And he describes how they’re trained to be a leader or a follower, literally, at the coalface. And they’re switching the decisions about who’s leading and following in microseconds, as the situation is changing.

As a metaphor, if I said, “Oh, let’s go out for a meal tonight. Would you like to go for a pizza?” And someone else says, “Hey, what about Chinese?” I was leading. Then the other person suddenly led and said, “No, let’s do the Chinese.” And you’re switching the lead/follow just in the conversation. But to have teams working really effectively with leading and following at the coalface given the responsibility to go and deliver in that little unit. Like Matt in New York with his four staff growing that 20 million revenue, it’s not like, “Oh, Matt, you’ve got to do this.” No. You can go and do what you want to do. Let’s just be clear about the desired end state.

So look up Larry yatch. He’s got some really good ideas about the role of the manager. It’s all about direction and support, very clear sense. Number one set and communicate a clear desired end state. And I find often in the passion of startups, everyone’s running around like headless chickens, they’re not really clear exactly what the big mission is. And they’re not clear what the quarterly elements are. So you need discipline to come in and really help with clear communication out on what the desired end state is. And then just faith in people. And let them make lots of mistakes.

So leadership is about creating the environment. So this is more than just the culture. But the environment is such a spectacular way that you enable people to get on and do what they need to do. I didn’t do that in Muscat at all. And I think the success of Grapeshot was not just that cultural spine, but the way of working with staff, it’s probably a more modern way to do it. But there’s a lot of good resources out there to read. And I wanted to show a video of my granddaughter climbing up the stairs, and the way that you go up a step, and then you fall back tw?o, and then you go up again. And it’s just wonderful to see a young child learning about the material world around them.

But this lady is really quite spectacular. I don’t know if anyone’s come across Regina Dugan. She was at DARPA, and then went to Google, and essentially managed all the innovation hubs. And she always worked with small teams at Google, about 10 to 20 people. And she literally had about 100, or 200, mini projects running across lots of different academic institutions. But her philosophy I think, describes what all of us should be putting in.

Regina Dugan

You should be nice to nerds. In fact, I’d go so far as to say if you don’t already have a nerd in your life, you should get one. I’m just saying. Scientists and engineers change the world. I’d like to tell you about a magical place called DARPA, where scientists and engineers defy the impossible, and refuse to fear failure. Now, these two ideas are connected more than you may realize. Because when you remove the fear of failure, impossible things suddenly become possible. If you want to know how, ask yourself this question: What would you attempt to do if you knew you could not fail? If you really ask yourself this question, you can’t help but feel uncomfortable. I feel a little uncomfortable. Because when you ask it, you begin to understand how the fear of failure constrains you, how it keeps us from attempting great things. And life gets dull, amazing things stop happening. Sure, good things happen. But amazing things stop happening. Now, I should be clear, I’m not encouraging failure. I’m discouraging fear of failure.

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.

John Snyder

I’ll stop there. I think failure is a really important thing to discuss. I remember, an inbound member of staff said, “Look, we’ve actually got to openly talk about failure.” And I finally hired a CTO, I think, in year 12 – of a 12 year journey – employing a lot of software developers, but he was an absolute rockstar in top agile development methods. And he described a previous employee where he blew up literally a whole server system that managed an online gaming company. And at the big company away event, they put a tower in the Furneaux picture on the thing, and then he invited him on stage and literally celebrated his CTO failure of the whole thing going down. And that’s a really important lesson in terms of the attitudes because you get a lot out of your staff if you allow them to fail. Because they experiment and they innovate very, very well.

So let’s talk about some of the moves you make. You’ve got to make real choices about your time, when to go to New York, with what effort? Lots of money? Employing that big sales director that knows how to do the bullet point slides? Or growing it, transplanting like one of Marks pencils, you know, put a little pencil in New York with your own culture and see how it grows. So here’s my Motley team. We’re in the keyword technology.

So, a great thing, put keywords on the back of business cards, because when you hand it over, someone goes, “Oh, you play chess, or you kite surf.” And suddenly there’s a very fruitful conversation very quickly. On my business card, I reveal mine at the end of the slide deck, and you’ll see mine. And literally, by the time I’d walked down to the floor, a head of a really big customer group emailed me and said, “John, I do all three like you. Let’s meet up.”

But how do you actually get a scrappy culture going with a motley crew? Well, I was leaving New York and I suddenly bought a GoPro, because I like a bit of gadget. And this GoPro led me to an office at 30 Wall Street. How did that work? How do you surprise yourself? And certainly your chairman. So this is a really bad video. And my chairman would say, “John, why are you spending your time running around with the GoPro?” So I’m going to share this one. It’s only 90 seconds. And it’s very scrappy, and it gives you a sense of how scrappy we really are. So this is my first GoPro video.

South of Chamber Street is Wall Street, the world’s trading center and equities market. Stocks are bought and sold in milliseconds on the exchange as traders buy and sell shares using algorithms on electronic trading platforms. Manhattan has always welcomed new people and innovation to its shores. New York is the center of the world the stock markets and traders, but also home to big brands and the world’s largest companies engaging with the market.

In a distant land in Cambridge, England, computing research at Cambridge University has developed new algorithms for understanding Internet content. Grapeshot analyzes 15 billion bids on ad exchanges each day, grapeshot software helps traders decide which ads to buy. There is a big sea of change as real time bidding on electronic ad exchanges becomes the new way. Instead of tracking people around the internet using cookies, Grapeshot converts the needs of brands into keywords, so traders can find relevant and safe ad slots. Grapeshot has created a new platform technology for brands to use real time bidding, many trading desks are jumping on board. 1000s of brands are already served by Grapeshot with 60% of online ads to be traded on exchanges, New York must assert its lead. Manhattan is where media and trading can mix. We are coming to lower Manhattan with your help.

So the real story there is I’m six weeks into Manhattan, hot desking at a friend’s desk before I brought those junior people over. And I asked a friend how do I get an office and he said, “Well, there’s this competition.” So 300 companies applied, and we were one. So I buy the GoPro, you see me filming my children on the beach. So somehow I worked into the video when I was told “Oh, you’ve got to make a video, because you’ve been shortlisted to 20.” So I thought: “Well I’ve got a GoPro, buy an apple Mac, iMovie edit it together.” Everyone’s quite excited I’m making a video. And then I’m told on the day when you have to give an elevator pitch as well. They said, “Oh, no, you had $10,000 to make a video.” And so I was the only one who did a homemade one. Everyone had a slick one. But I was able to tell my story. And I won.

So I won a quarter of a million dollars. And essentially, I then got an office in Wall Street. But the office is quite big. So what did I do? I sublet some of the space to one of my customers. And guess what: I learned a lot about my customers sharing an office. And that was a really good investment. And it all came from being scrappy, and getting a GoPro out going and doing stuff that you wouldn’t otherwise normally do.

So, it’s fantastic because we witness Lower Manhattan, the Freedom Tower, being built. I think we had a rave party on the 35th floor as we were building it. We’re in hardhats, it was brilliant, seeing their commitment to really growing Lower Manhattan. Now, all the big media companies have moved down south towards Battery Park.

So, diversity in the team. These are just some of the people we have, but it’s just wonderful. When you shrink it down, these are personalities. These are people who have a reason to come to work. My job is to invent the man on the mission desired end-states, getting them really excited and to really work inside a fusion of one company. So I call this people sculpture. I had the benefit after Muscat of setting up the Cambridge entrepreneurship center, with colleagues and running the business creation function and a whole 100 person mental team.

I find it fascinating: how do you evolve a company over time? Lots of people don’t understand the difference between pre sales, post sales, support, marketing, what is product marketing compared to other marketing? Very few people know what they’re building. I mean, as an architect, you try and build a design before you went forward and built something. And often we’re running our little companies not really aware of what the next stages are. Like that hopscotch picture I showed: what are the moves? And how are you going to sculpt these people together? It’s a very important thing to consider how you sculpt. Here, we’ve got Joy, she was based in Singapore, took a long time to persuade her to help set up our Shanghai business but she will be part of it.

Adam here, he made a fatal mistake. He basically put “Ping pong ace” on his card. And I used to play table tennis for my school. And I could beat him. And I’m very competitive. But I got to know Adam really well. And he was just a young, Italian Jewish New Yorker and got a great attitude. And he ended up saying, “Okay, Matt doesn’t want to go set up Chicago, I’ll go and set up Chicago.” And he just went there cold, and started to get his own network. And just before the sale, I went to his office, and I was so surprised. It was a small, WeWork cubicle, with literally four people. He said, “You know, John, I booked more revenue than the whole of your European and Asia-Pacific operations together.” Absolutely impressive. And again, that was young culture incubated in New York, and then able to spread.

So when I show you a map of where we went, we basically put in little franchise teams, a salesperson and account manager just two peas in a pod, you train them back at base with the culture, and then the two of them, one, and then followed by the other, go and basically plant themselves around the world.

So agile team development, how did I do this? Well, pretty much like Dame Shirley said herself, how to manage people? You soon realize that you’re the entrepreneur with a vision, you know about man on the moon, but you don’t know how to run a whole set of operations. So for me, the game is always to wait as long as possible, to get the most expensive people and experience people into your team. Often we hurry forward, we think, “Oh, we’ve got this need. I need a CTO.” The board and the investors are saying “Why don’t get a CTO,” I’m like, “No, I gotta wait. I need the best best talent into the team.” And I got a COO who is an absolute Rockstar in terms of developing the team and getting more muscle. He called it tone and muscle in the organization.

So you need to start building other people around you that can fill the gaps you definitely don’t have, and always recruit more, better. So this chap on the bottom right, very relentless. He’s called Kurt by name and he is curt by attitude. But it takes a lot of difference and diversity on the team. How do you build that: I’d say friction. People hate friction in their day job. Customers hate friction. So you’ve always got to tack every single morsel of friction and take it out. It’s all the negative stuff.

I have three questions I always ask at interviews. I won’t bore you with them. But one of them is I ask them the three things you don’t like when you come back from work and you’re agitated. A lot of people hit on friction. Colleagues who don’t do what they said they’re going to do, but friction, this kind of aimless stuff that takes your time. I think another culture thing apart from failure and recognizing failures, is: “Okay, we go here. We go into this crevasse full of danger. We’ve got limited resources, we’ve got limited effort. We’re going down that crevasse, right, let’s go.” So out of lots of customers, I think we had 900 trading desks and about 9000 brands or something. But we go: “Right, we’re going here.” And so that’s what a leader has to do, really say: “Right. This is where we’re going, we make the choice, and we all go in there together.”

So one of the sales directors says, “You’ve got to do 7 million this year.” And you say “I can’t do seven. I’ll do five. I needed 2 last year, what do you mean, you want me to do seven!?” But you’re really stretching the goals. And what’s amazing, is when you really twist their arm, and you really force them to do it. They do it. But they didn’t want to do it. So I remember pushing someone from five to seven. And he was just angry. He thought he wasn’t gonna get his commission and everything. But he did seven, you push them. Now if you had children and other young members of your family, you know it’s all about stretching the goals. It’s exciting.

I think one of the things we didn’t do at Muscat, we just charged at it, but at Grapeshot, we put a lot of work into trying to understand the customer journey. We were trying to reduce friction in our work processes and the like, how can we understand the customer? I don’t know how many of you do customer persona work, but it’s absolutely vital.

I used to use Salesforce and Pardo, but I’m using HubSpot now. And Hubspot’s got some great Academy material. So go to HubSpot, get a free CRM sign in and start looking at growth driven businesses and how to design CRMs and CMSs for them.

So customer journeys, it’s a really important part, this is where your culture is reaching out, not to colleagues, but to your customers in the same way. You’ve got values, and your customers recognize those values in the way you behave. And they’re going to really help you. And I think my pivot from what’s called the sell side of the market (publishers) to buy side (advertising agencies), literally was a customer. And after I sold, Tim wrote to me and said, “You know, John, what I really like about you, is you never took me out for lunch.” Seriously, there wasn’t the bribery, there wasn’t the pushy, there wasn’t the salesman, it was an intellectual engagement. Asking: how can we join forces? How can we solve this problem together? We’re excited by our game. We love playing chess, we’re not here for money. And those things make a difference.

So I mentioned the franchise model. So we got to New York, and then we grew a very big team, about 60 people down in Singapore. And then we just started to go around the place. I think China was really interesting. But it’s always the same model, just junior people incubating the culture, and then put a senior person on top after that, if need be. But Muscat, I remember writing to one of my biggest customers saying, “I’m not sure I can do this deal International, because I haven’t got the staff.” I remember I was limited by my own glass ceiling. So with Grapeshot we were global day one. I think one of the first trips I did was to China, and realized I was too early for the market there. But having worked with RDAs and all that public sector work I did, I just realized there’s a big globe out there, we should go and attack it head on. So I hope some of you are already thinking absolutely global.

Now the hardest thing with technology people, we might have Scrum, we might be able to do all the user requests, the jobs to be done, user stories. But very few of us are great at making boxes with ribbons. Now, you might think you like chocolate, you’re not buying the chocolate, you’re buying an experience. And I spent a long time at Grapeshot trying to say, “Look, I’m more interested in the color of the ribbon. I want the color of the ribbon, the size of the box, and I want you to understand how that fits into the way the customer is thinking.”

And again, the culture has to be much more customer centric: what are you trying to sell? People say they don’t sell drills, they’re basically selling something to get something done. It’s called put the shelves up, you’re actually buying a drill to make a hole to put the shelves up. But the job to be done is not to get a drill. And it’s very vital that we put ourselves into this sense of the customer, just like we wanted our staff to be our best fans and we wanted our customers to be our best fans. And you’ve got to work hard to understand their psyche.

So product marketing: very, very important. It was really nice, actually because when we got acquired, I remember some of their team was saying, “The way you do your agile and the way you’ve got your product managers and your product marketing, we just aspire to do this.” And you’re talking about one of the largest US software corporations. So it’s nice to know that we’re actually doing things pretty much on the cutting edge.

Certainly at Muscat I didn’t do it, and Grapeshot, we took a long time to get there. But how can you fly an airplane without all the instrumentation? I think a lot of us don’t put instrumentation in early enough. It’s not your website stats. It’s everything that your team is doing. Trying to get a sense of: are we killing left or right? So not only does the customer want the data analytics, but you want it fused in your business. So we ended up with dashboard showing our customers and what they were buying day by day. And so we can really see that signal. It wasn’t done at the end of the month. It was real time data. So we knew exactly where to put our effort. We’ve got limited time. We put our effort there. Data Analytics helps us solve that problem.

Innovation, we used to have innovation lunches. People would put things on to the table, we used to have one day out of five, you can do your own thing as developers. All those sorts of things that I think are pretty normal these days.

We heard it from Dame Shirley as well: losing control. I did feel at about 200 staff, I was really losing control. My culture was changing with all that different senior management in there. You wrestle with it. Because it’s like faith in people, you’re giving them that ability to do it their way. So how much control do you wrestle back, and when do you release the reins is something that you’ll find on your journey. But you’ve got to let it happen. You have it with children growing up, they become teenagers, they behave very differently in the teenage era. And companies are like that, as well. They’re growing.

But what I think was so fundamental to our business, was the strategic partnership. So a lot of people, they have customers, and they don’t actually think channel. When people make things, they don’t go to the retail stores, they go to the distributors. And it’s vital that you play your chess game by calculating exactly the right steps, when to go to the channel, with what evidence is a direct client solving their problems? And how do you activate that channel and really move it?

So if I show this slide, this is one of my favorite slides. You won’t know our sector but I remember signing a deal with AppNexus. In New York, they were all the rage. All these other technologies on the platform, we were the last to arrive in our category. And I remember a consultant in New York said “John, contextual? contextual? That’s like old hat. What are you selling here? You’re crazy. And you’re the last one to the party.” But we ended up being the most used app on their platform, because we had simplicity. And we had a good simple story. And we were passionate as a culture. And all those young people were just delivering the best service out, because they had the mission.

We got on some other platforms, and one of them – Trade Desk – actually floated more recently. And I used to earn sort of 30/40/ $50,000 a month on their platform. And we framed it when we did a million dollars a month with them. And then we framed it again, when we got a million and a half dollars. A million and a half dollars a month from one partner. That’s a lot better than going direct to all those end customers, just one invoice. One relationship. It’s a much easier way of building a business. So we actually signed up about 40 partners. And you can probably see with the revenue curve here, it starts to get faster and faster and faster.

So it’s how you play the chess game. How you put your pieces together, the staff, and the like? How do you get that equilibrium in such a fast changing exponential world? I have to say: culture. Culture every time. So my question to you is: what are you investing in your culture? How do you do it? Is it just pizzas and beers? Were you really thinking about it?

We developed an academy where any new employee flew to Cambridge, whether it’s from Shanghai or Hong Kong, and they got inducted in our company for a week. What we forgot was our existing staff, they all wanted to go on the induction and get the more up to date knowledge of the business and how we’re working. But it was a great way to run our own little Academy and get that culture fusing in and out. And the people who weren’t married or partnered up, they would actually do flat swaps. So someone in New York would suddenly come to London for a month. And another colleague in London would go and live in his flat or her flat. And it was really nice to give people that opportunity to go abroad and mingle. But it’s really about that culture.

So from my little award, that GoPro thing, I thought I’d show you where our culture got to about a year before things happened. So let me do this.

Video

Time is money. And so are words, we consume 1.5 billion words every day. There is no want for information at our fingertips. But there is an even greater growing desire for hacking through the jungle of data overload, that is tripping, diverting, and generally sucking in valuable time and money from our every step. Wasted time and effort keeping us from getting to the relevant answers we want, in the moment that we need them. We think this diversion of human energy is the bane of getting things done. Positive energy that fuels the purpose and good that smarter more relevant brands can bring to the world. So while some find it cool to have a continuously flooded ocean of data to drown it, we find it oh so much cooler to deliver just the right thing for the job at hand. Faster and simpler. So you can get to it. Grapeshot.

John Snyder

So, we synthesized everything we were passionate about: the idea of helping in the advertising world, there’s billions and billions of ads, we’re helping brands actually find the very few pages that were specifically talking about the thing they were trying to sell or resonate with. So Nike could literally target someone winning the 100 meters at the Olympics, and effectively, immediately put the Nike branding all over those stories that are breaking around the internet. As that Olympic champion won their title.

So our product helped people get to it. But getting to it and taking out all that noise, that friction and just going razor sharp for what actually matters. That was our calling cry. So until we changed it to something like “contextual intelligence,” “Get to it.” Every meeting ended with the phrase, “let’s get to it.” It was just a bundle of positive energy motivating the team to get to it. That was the shorthand phrase. But, it really stimulated everyone as they went through.

Now, the challenges ahead, there’s lots of challenges. And I think as you grow, you’ve got to be clear who’s doing what around the management table. So I ended up always thinking several moves into the chess game. Where are we going, how are we navigating and how are we twisting and turning? That’s very different from someone saying, “Where are we now?” So I had operational people basically running the ship, they had the wheel, really thinking through: what’s happening right now, what’s not working, what do we have to achieve? I needed the freedom to really step ahead and be several moves ahead in the chess game, otherwise, you’re not going to win that chess game.

And how are we going to get there? Again, another operational question. So as I’m now accustomed to do, I do all the things that I like to do. I was in the Bahamas, kitesurfing. And I just wanted to show this as a metaphor, so you could visually memorize it. So here, you’re bobbing along, it’s a busy boat, it’s bumping up and down. This is operational focus, this is q1, q2, we’re in the quarter. It’s noisy, and it’s just, and then suddenly the CEO is putting a hand in the spray. And feeling where we’re going on the boat: are we gonna go left or right, they’re completely different. Now, the metaphor was shared at a networking event, it was actually the CEO/founder, feeling the waves and getting a sense of where the markets going, listening to the market, absolutely vital.

It’s a very different skill operating, and getting the right people to actually set those OKRs the opportunities and key results, the discipline OKRs. And having people familiar with it, I wasn’t until I hired a great person to come in. People knowing the desired end state, saying how they’re going to achieve – it in the Larry Yatch – language, and then sharing it with people. As we heard earlier, Dame Shirley: if I see someone else’s OKRs I know how to help them. So if I see published what they’re trying to achieve in this quarter, I have an opportunity to know how to help them to achieve what they’re trying to do to get to the common desired end state.

All right, let’s go back to this. Right, we’re almost done. So it’s strange, actually, when I think back to the first time I saw this diagram, I was probably still running Muscat. Shai via carnem – who ended up being a colleague at the Entrepreneurship Center – was teaching about strong teams and that real successful companies are not individual CEOs. At Muscat I was the single CEO. Yes, we ten-exed. Yes, we made some money. But the real privilege is to assemble – in that people sculpture way – a really good quality team and know who’s out on the bow. Know who’s on the wheel, know who’s doing X, Y Z for that shared desired end state. I like the fact from an engineering point of view, a typical install would do three and a half million queries per second. We had one millisecond in which to deliver our data. We shipped it to 148 countries. We did trillions of requests.

And the guy who actually ran the back end of that who worked with me at Muscat. I came to him.

I said, “Look, can you come help me at Grapshot?”

He said, “John, I’m busy. I’ve got other things.”

I said, “Well, one day, one day in this company, we’re going to do a billion calls a month.”

“Got me interested here.” You know, because I know why he comes to work. He comes to work for challenges, not for money. So I got him in.

He said, “Only if I can bring a solid guy, Mark.”

And essentially, Batman and Robin came to work for Grapeshot pretty much day one. They took it all the way through. And they love their job so much. They’re still now working at Oracle. Because it’s great solving these problems. To the extent that the company that acquired us are like, “How do you do this stuff? How do you get so much efficiency out of your operations?” Well, that’s the magic of the Batman and Robin team that I hired, we got a gross profit of 94% Pretty good. We were 20% EBIT profitable. We’re growing 180% year on year.

And what makes these things happen, and go exponential, is a great team. And what makes a great team is culture. And you have a responsibility not only to be obsessed about your customers, and your staff, but your customer obsession is just a reflection of how you obsess around your team. And the real art is definitely listening.

So just like that David Gilmore, guitar solo if you don’t listen to Comfortably Numb from Pink Floyd, really spend the attention to listen, not sell/project, listen. And you can do amazing things.

I think that is the end of sharing some signposts to culture. Thank you very much.

John Snyder

John Snyder was CEO (until his exit to Oracle) and Co-Founder of Grapeshot a global leader in contextual intelligence with offices in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Toronto, New York, London, Cambridge, Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Sydney.

Grapeshot applied advanced keyword technology to the programmatic advertising market. John has spent his whole career in the field of information retrieval and keyword technology, with a successful exit of the Muscat information search business in 1997, and a series of angel investments in hi-tech startups. He holds a BA Honors degree from the University of Cambridge, where he remains a Fellow in Entrepreneurship at the Judge Business School.

Next Events

BoS USA 2024 🇺🇸

🗓️ 23-25 Sept 2024

📍 Raleigh, NC

Learn how great software companies are built to help you build long-term, profitable, sustainable businesses.

‼️ Price rises July 26th. Register now.

The Road to Exit 🌐

🗓️ Next Cohort Starts September 2024

📍 Online Mastermind Group

A BoS Mastermind Group

facilitated by Mr Joe Leech

‼️ 2 Slots Left.

BoS Europe 2025 🇬🇧

🗓️ 31 March – 01 April 2025

📍 Cambridge, UK

Spend time with other smart people in a supportive community of SaaS & software entrepreneurs who want to build great products and companies.

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.