Infinite data means infinite metrics to measure the growth, value and health of SaaS and software companies.

In this session, Lauren will share insight, based on benchmarking top quartile SaaS companies, on what the metrics mean and what really matters to you. She’ll show how and why the metrics top performing businesses focus on have changed in the context of current economic climate and why focusing on a single metric is generally a bad idea.

She explains why you need to know your ‘magic number’ and the value of the ‘Rule of 40’ before opening a discussion on what metrics you could consider when building your performance dashboard.

Slides

Find out more about BoS

Get details about our next conference, subscribe to our newsletter, and watch more of the great BoS Talks you hear so much about.

Transcript

Lauren Kelley

This is the only conference I’ve ever been to where I’m giving a presentation and people say to me, I am so stoked to hear about your metrics. Like usually, this is a pretty dry presentation, but I decided to let me make sure I can work this right. I decided to learn from this conference. This is such an awesome conference, such a great community. We had such a fun time with the speakers last night. I was so impressed with everyone’s stories, so I thought I would take Chris’ awesome presentation yesterday and tell my story. So I don’t usually do this, so this is my first time doing this.

My Once Upon A Time

So once upon a time, I spent lots of time working in tech companies, years and years and years. I started out actually as an international economist doing trade negotiations right out of graduate school in Japan with the US government and Japan. And then I got really frustrated with working in the government. So I was lucky enough to get into a program where I did a mid career thing, and I went to work in the German economics ministry to work on software regulations in the fall of 1989.

So very soon thereafter, about a month later, the German government was not, this is West Germany bond. They weren’t super interested in the European Community software regulations. They were concerned about bananas, because when all the East Germans came over the wall for 40 years, they hadn’t had bananas because the banana trade is very controlled and based on old colonial patterns. So we spent all this time and they hadn’t had access to cinnamon and nutmeg. And so if you know, when the wall fell down, it was October, November 89 what comes next? Christmas?

Literally, every store along the West German border was stripped bare because the East Germans hadn’t had access to Lebkuchen, which are the little cookies that Germans make for like, 40 years, because if there was any cinnamon, it went to Russia, not to East Germany. So it was an exciting time. I ended up saying, it’s a lot more fun being here in Europe. I want to work in you know, I’m sort of tired of I’m an analytical person, but also operational. So I ended up with compact computer helping start up the East Central and East European business. We built it up in a couple of years to about 160 million.

Then I met my husband, who was a American journalist in Paris. Went to Borland in Paris so I could live with my husband. And then I came to Boston because my husband dragged me out of Paris after dragging me out of Munich to go to Paris and started with an early stage startup software company. These guys straight out of MIT, a company called Art Technology Group (ATG). They’re actually the ones who invented the personalization on the web. So all those cookies that track you today, blame it on this company. But anyway, it was a small company. Worked really hard. I ended up running all the sales revenue operations. We had a, you know, that’s what I did every day. I’m trying to follow my script. And we did great., took the company public, really proud of the fact that in one year, we did 35 million. We went public, then we did 160 million. Then the internet crash came, and lo and behold, I was really proud of myself, because in the first half of 2001 when everyone was crashing and burning, we did 40% more than we did in 2000 when we went from 35 to 160 million. And how did we do that? We did that because I have an analytical background, and I’m very numbers driven, and we. had great technology.

However, then one day, talk about an obstacle. This is kind of a personal story. I actually had a ticket on a flight from Boston to California, and I decided not to take that flight and to go the day before, so that I could get a good night’s sleep, because I had these big, big meetings, and lo and behold, I got to California, I wake up the next morning, and that flight was toast. So that was my obstacle. It was also the end of the third quarter for our company, which was a public company.

So I have actually never, you know, I guess I just got emotional there. But I have never missed a quarter. I’ve never missed a target. We totally missed the third quarter of 2001 it’s kind of hard when you’re you know, you think it’s hard when you have investors, you think it’s hard when you’re beholden to your employees, but it’s really hard when you’re a public company, and it gets like lambasted everywhere that you’ve missed your numbers. But luckily, we were in good company, and everybody was crashing and burning.

So the story ended up fine. The company continued, and then was acquired by Oracle. I went and spent some time as an executive in residence at Softbank who had invested in us and done really well so and as I was doing, as I was sitting there, because I just wanted to understand the investor world, because I’d been an operator and an analyst for so long, and I just didn’t really understand other networks. And I just was amazed at the sort of difference between the way investors looked at companies just purely on financial statements, and I’m like, but that’s not really how things work. I mean, there’s so much underneath that. Why aren’t you looking at that stuff to figure out if this is a good company, or where it’s going, or any of this stuff? And it’s just day after day we kept looking at these companies. It made me crazy. And I never thought I could start a company, because I’m not a computer scientist, I’m not an engineer, but I know something about data and I know something about business.

And so I started a company called OPEX engine, and that’s what I’m going to talk about, is what we do, which is benchmarking B2B software and SaaS companies, we focus entirely on companies with revenues between a million and a billion. So that’s what those are, the metrics I can talk to you about now. I can pontificate about other things, but that’s what I know right now, and it’s we were acquired two years ago by Bain and Company, but we’re still an independent company. We have about 1000 companies on our platform, and the difference with what we do is that it is it’s like an audit, it’s a benchmarking, except for it’s a platform where companies work with us to put in their financials, their SaaS metrics, their unit economics, and then for every major company, a major department of the company, sales, marketing, R&D, G&A customer success, HR, we look at expenses, head counts, major categories, performance metrics, so that you can get a 360 view of the company.

So our customers use this for budgeting and for planning. But with the current market environment, what we’re seeing the most of right now, and we typically now are working with companies that are, you know, at scale is focusing on margin expansion, margin expansion as well as growth efficiency, because that’s really where the market’s getting to. The rules really have changed for SaaS companies. You can argue about what generation of SaaS we’re in, and does anyone have any question about what I mean by SaaS/Software as a Service, which is both a distribution model as well as a licensing and business model. So you sort of, you need to have both to really be considered a SaaS company. SaaS companies have been considered. They have higher multiples. They’re very valuable. Incredible amounts of money have been invested, and that’s because it’s a very powerful business model.

But what’s changed is that in the last couple of years, so much money went in and so much growth. I mean, people ask me about, how do you bend? You know, do you benchmark based on industry? Like, is this a FinTech company? Or is this an ERP company or whatever? And I’ll say it’s, it’s, you benchmark companies by definitely the stage they’re at.

I was on a call yesterday with a couple 100 million dollar payment platform that wanted to compare themselves to Stripe and PayPal. And I’m like, on head count. I’m like, Huh? You know, I think Stripe’s something like 15 billion, and PayPal is 25 billion, something like that. I mean, it’s and they said, Well, that’s best in class. Well, their numbers of head count are not best in class for a $200 million company. I mean, it’s just there’s that information is not going to help you.

And I think that’s part of the problem. Is that in our industry, the tech industry, there’s just so much hype and so much sort of, I don’t want to say vanity, but maybe vanity. Bob’s nodding. It’s fair. We’re Midwestern, so we can say that. So definitely, it’s a crazy market. Is it going up? Is it going down? I think there’s a couple of things that we know is that digital and cloud applications are going to continue growing. They have one of the highest growth rates. I think I don’t know what the last Gartner report is, maybe 22% for SaaS. That’s higher than a lot of other industries out there, pretty much anything out there. But what you’re seeing, and this keeps you know this ’23 has been a really interesting year to watch these things.

The key thing to look at on this chart is the green line at the top. And here I thought, I’ll take America’s growth capital index, because I love America’s growth capital. They’re a big, big investment, tech investment bank based in Boston, co founded by a woman so very productive company, because I’ll show you in the data that women, you know having women in your management team does, if anyone wants to see that after the presentation, it does tend to have higher returns. Not that anything’s wrong with anything else, and lots of companies have great returns. What is that I’m trying to do, that thing you do at the end of stock calls.

So the point here, the considering, look at the audience, the line here, the green line at the very top, is price per earning share multiple. So the point here is that up through middle of last year, SaaS companies were primarily valued on a multiple of revenue, and now there it’s evolving towards a multiple of revenue plus earnings, or revenue plus profitability, and that’s where the rule of 40 comes in.

Rule of 40+

Has anyone here? Has everyone here heard of the rule of 40? Okay? Tell them, tell them. Tell them, tell them.

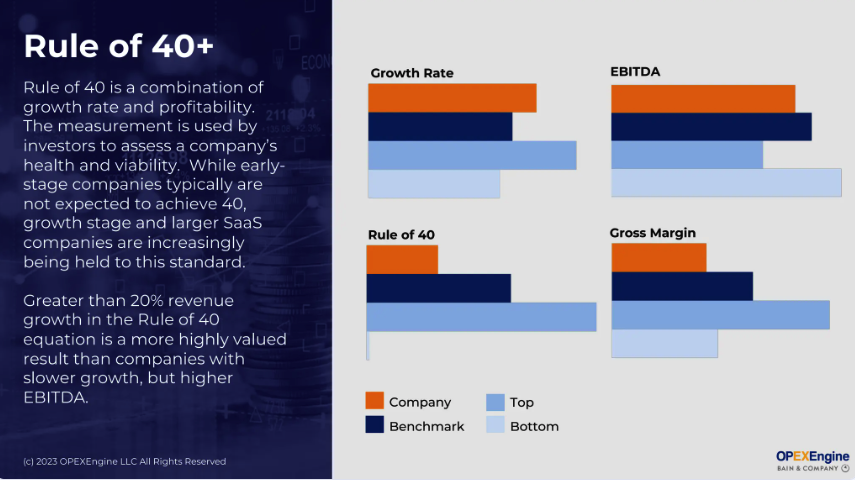

So the rule of 40, a simple way of looking at it, is to add your growth rate and your EBITDA, or free cash flow, and you want it to be around 40. Now, if you’re under, you know, if you’re a small company, if you’re an early stage, don’t worry about it. It’s not going to happen unless you have some amazingly profitable service business. But if you’re a tech company, it’s very unusual to have a 40 on your rule of 40 at that point. But if you’re at, you know, 50 million, 100 million, if you’re looking for private equity investment, investors are always looking at rule of 40.

However, not all things are equal, like it’s not even you can’t have if you have 10% growth and 30% EBITDA, which equals 40, you’re not as valuable as a company that has 35% growth and 5% EBITDA, or if you’re a category leader, and you have 80% or 120% revenue growth and you have 100, you know, negative EBITDA, you can still be a hugely valuable company. So it’s not a perfect but it’s an indicator, and it’s a good thing to be aware of, and that’s what investors are looking at. So they’re looking at rule of 40. They’re looking at unit economics.

So unit economics a Boston venture guy David Scott, who also was on the board of HubSpot, who is one of our longtime customers, kind of popularized the discussion about unit economics, which is basically looking at your cost of new customer acquisition. So new customer acquisition that’s in an early stage company. It’s easy enough to take your sales and marketing, because pretty much all your efforts are around new customer acquisition. As you get bigger, it gets more complicated, because not everything you do is around new customer acquisition. You also are focused on retention and branding and things like that. So you have to separate out within your sales and marketing expense, what portion of it goes to new customer acquisition. So that’s CAC, and then you have customer lifetime value.

So customer lifetime value is how much is this customer worth to me over the long term. And typically, you take the average the annual recurring revenue and multiply it by your gross margin. And an important thing there is some companies like to tweak that and use the gross margin just for their recurring revenue. But if you have a lot of services in your company, your gross margin is probably lower when it’s blended. So unless you could live without that services business, if you want to know internally, really what the value of each customer is, you should take your whole gross margin. And then in your denominator, you take your customer retention rate as kind of the probability that you’re going to keep this customer.

So it’s just think of it really simply, if you have a 90% customer retention rate, which is the units of customers, not the dollars of customers, the units of customers. It’s like 90% chance, then you’re, you’re sort of shaving the cost of, you know, the value of the revenue that you got by taking off 10% because you may not keep all of that. And so then you compare your customer lifetime value to your cost of customer acquisition, and you get what’s called the CAC ratio, or a CLB to CAC. And then you can say, you know, and typically it’s good to get, like, 3x but all of these things are sort of a trend, you know, a point in time, and there’s a difference between where you’re at right this minute and where you want to be in steady state. So that’s unit economics.

Go to Market productivity. Another guy, Rory Driscoll, another VC who invested in a company called Omniture and the CEO of Omniture, presented this, you know, great metric called magic number – which effectively is just looking at, for every dollar in sales and marketing, how much new recurring revenue are you getting? Just simple and a real simple rule of thumb, you want to be somewhere between 0.5 and 1.5.

If you’re under point five, then you really have a problem on your sales and marketing side. It’s really not you know that means you’re getting less than 50 cents of new revenue. That means you need to really dig in focus on your sales and marketing, efficiency and productivity. If you’re between .5 and 1, it’s good. Could be better 1 and 1.5 that’s really great if you’re 1.5 and more, unless your whole goal is just profitability. Maybe it’s a lifestyle company. Maybe you’re just taking money out, then you could probably be doing more, like if you’re over 1.5 typically, the wisdom is, do more of that. Invest more in sales and marketing. You can validate that you’re getting customers for every dollar you spend in sales and marketing, that’s a good thing. And so then we came up with another metric called R&D ROI, which basically sort of does the same thing as the magic number, but for R&D.

I used to run CFO meanings of our. Customers in Boston, in Boulder, Boulder, in Denver, great tech community. And then, you know, in San Francisco and in Silicon Valley and Austin. In every meeting that we would have for years, CFOs, when we’d start talking about R&D, CFOs would always say, how do we measure R and D? You know, I don’t really know. I get all these activity reports, and I look at, like, what percentage of revenue is spent on R&D. But if I look at the, you know, the public companies, it’s like, all over the map, and it’s just a, I kept hearing the same word. It’s a black box, like I really don’t know what the productivity of R&D is.

So we take last year’s R&D spend and just compare that to the new revenue this year. So just between January and December 31 your change in revenue. So is your R&D getting you new revenue or not? Because, let’s be honest, this is a SaaS company, and I think to Claire’s awesome presentation just now, you can have all these cool projects. And, you know, tech companies are usually run by tech people and want to change the world and want to do things better, but are they really producing revenue, or is this just some new, you know, great thing? And so it’s a great measure to keep everybody sort of honest. And these are what I call just really be clear that, though, that these are indicators, this isn’t a diagnosis. That’s where we come in. That’s the kind of stuff that we do is dig in. Okay, so if these indicators, and you can use our stuff, you can use there’s loads of stuff out there. You can do the calculations yourself. You can compare to all sorts of companies. You know, there’s loads of information on the on the web, but if you want to dig into it and then diagnose so I want to be better here, then that’s the kind of things that we do.

So I’m, I just became such an incredible believer in in benchmarking and data, because I went through that really tough time in 2000 you know, the the pinnacle of heights down to the, you know, the worst bottom 2000 to 2001 I mean, we were like our my boss, the CEO, was spray painted gold on the cover of Boston Magazine, and then we had a unfortunate customer meeting that people got a little crazy. It was in the front page of the Wall Street Journal, really embarrassing for me. So how do you manage through these kind of things? I think you manage through it with numbers.

The other thing is, I mean, look at me. I’m I’m a woman. I’m not like your aggressive, like wild, you know, typical sales person, but I’ve done really well relatively in my career, I’ve helped take a company public. I’ve benefited from that. I just sold my company, benefited from that. I’m blessed with two crazy kids, but I survive, and I’ve done well because of numbers. You know, how many times have you sat in a meeting and there’s some quiet person there saying the right thing, and there’s some person over there who’s like, aggressively saying what turns out to be the wrong thing, but everybody listens to the wrong one. Because, you know, that’s just how human beings interact.

But when you have numbers, it takes every, you know, all the emotion out of it, all of our customers, see, you know, CFOs also aren’t always the most outgoing people, and their job is to sort of herd cats, especially in the budget process, and to get everyone in agreement, they have to get the head of sales who in some traditional software situations, can always go to the CEO and say, Look, you want me to make this revenue. I need more people, or I need marketing to do blah, blah, blah, or it is the product’s fault, you know, whatever. And you know R&D, the CFO has to, like, figure out what they’re asking for.

So every CFO that we’ve worked with says it just makes our job so much easier when we can just show the numbers. Well, this is what other companies like us are doing, or this is what other companies have accomplished with these resources to Claire’s presentation. You know, it helps human beings sort of get on board when they can see the numbers of what other real companies are doing.

So the other thing is that 90% of the metrics that matter in SaaS are not gap financial metrics. So income, statement, balance sheet metrics are metrics that, you know, people go to university, get university degrees. They get CPA degrees to do, to manage that. You get auditors who come in and check it, and even then you haven’t calculated them right. And then we have the SaaS industry, which has run 90% on metrics that there’s no education in it, except for some like cowboys on the web, who are like describing everything and you know, and also great information. There’s investors who have both good intentions and, you know, other intentions in terms of what they tell you the metrics are and what’s a company supposed to do and figure out how to get the metrics right.

So I just, you know, my mission in building this company was, you know, come on, guys. I know everyone in software is a special flower, and you’re changing the world, but we can, we can share some of this best practices and and people are amazingly generous. I have learned from and my company has learned from so many absolutely amazing companies like HubSpot and Zendesk and DocuSign, these are all companies that we’ve worked with. There was a stack before. 70% of the SaaS IPO companies that have IPO in the US over the past 10 years have benchmarked with us at some point, and we’re just so lucky to work with these folks. But what we can do is, you know, we’ve compiled this best practices about metrics, so a large part of the process of working with us is companies put their data in. They work with our financial consultants to make sure that the metrics are calculated properly in fit best practices, and then all we roll everything up into calculated ratios, and then everything’s blinded and anonymized and goes into a database where then you can apply filters against it by your business model.

Are you a vertical SaaS? Are you horizontal? Are you selling a big, expensive product, even, you know, a million dollar product, average contract value, you’re going to have a different sales organization, different R&D than a company that’s selling, you know, highly transactional, you know, couple $1,000 product, high volume, or at least that’s what you’re trying to get to, totally different numbers. So you have to sort and segment that way.

And then the best thing about it, the funny thing is that companies always say to us afterwards that, you know, it’s never the buying decision, but afterwards they say one of the best things about this was getting everyone on the management team on the same page in terms of what the targets are, what the expectations, what, you know, the resources are. I used to have a boss in Germany who would drive me insane, because, you know, I’d get all excited about what the competitor was doing, and like, we have to do this big marketing campaign because they’re doing it, blah, blah, blah. And he’d just look at me and he said, We all cook with water. I’m like, well, that’s no help.

Basically, what he was saying to me was, we all have the same water. It’s up to you. Your job is to figure out where to put it and what you make out of it. So I’m not giving you any more resources unless you sell more. So it was a really good basis for learning how to run my own company.

So I wanted to talk a little bit because I’ve heard different bits of this over the last couple of days, and hopefully you can read this. My these are really, you know, improved slides. Usually the slides that we have are, like, so full of numbers and so full of things. I tried to focus here more on frameworks.

Three Types of Benchmarking

Internal Benchmarking

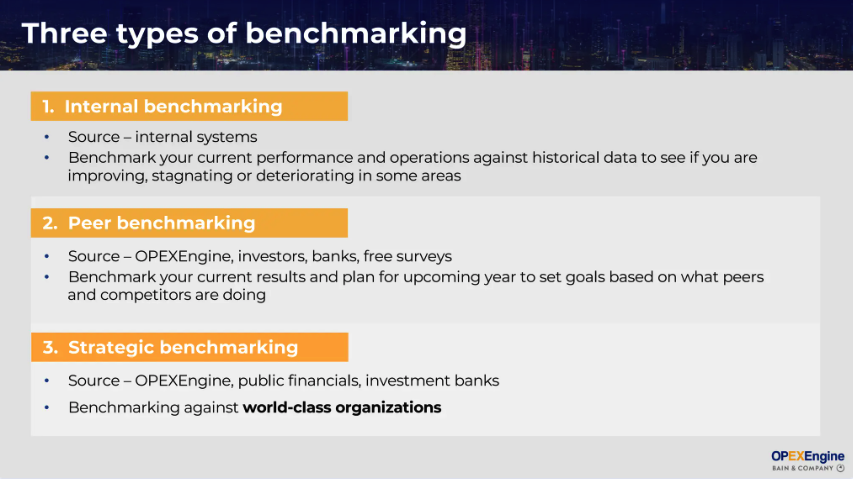

There’s internal benchmarking, where you just look at your you know it’s like staring at your navel, but it is a good thing. You got to know your your own numbers, but you’re comparing to maybe you had 50% growth since last year. Awesome. But is that good? Great or average? Compared to anybody else. That’s why you also need to look outside. So do the internal benchmarking, make sure that you’re looking and tracking the right numbers. But then also look outside, and there’s lots of sources of that.

Strategic Benchmarking

And then there’s strategic benchmarking, where you are thinking about going into a new market. You’re doing planning for the next two, three years. What if you, what if you raise that 5 million or 30 million or 100 million. What, what’s that going to do to your company? Like, how are you going to spend that? How did other companies do that? That’s the kind of thing that you can do with strategic benchmarking.

So I also want to talk about how people use benchmarks, because we see lots of difficulties there. So I spoke already about internal benchmarks and only doing that. It’s a good thing to do. It’s just not everything. Then the other thing that’s really hard is getting your comparisons right. And I’m going to show you an example of something which looks really close but gives you different pieces of information. So how do you how do you use it?

It’s really important to get the right cohort. And to my point earlier, about the $200 million payment platform that wanted to compare themselves on headcount management to Stripe or PayPal, just because those are also payment platforms, not going to be helpful.

Peer Benchmarking

The other thing is validated data. So there’s a lot of benchmarks out there that are generated through free surveys and through a variety you know, investors put a lot of things out, which is great. And, you know, I just happen to think it’s kind of like an audit. It’s worth paying for it to get quality and validated data. We do surveys all the time, free surveys even with our customers and even our customers, sometimes different people in the company will give us different numbers than I mean, even on simple things like growth rate, but things like CAC, you can ask three different people, or even one of the hardest things we have, sometimes with our own customers, is, how many customers do you have? Like, if you want to get average, you know, average per customer.

Like, who can anyone raise their hand here? Who thinks that they might have heard in their company more than one customer number from different organizations. So the CRM might have one set of customers. Because you know, how do you define a customer in sales? You would know this. You might organize it by territories or by, you know, if you sell to big franchises, is that one customer, or is that 2000? If you sell to IBM, is it IBM, US, IBM Europe? Is that two customers, one customer? Gets a lot more complicated. Do you take it out of the billing system is the billing system. You know, some companies use consolidated billing systems. So might show, like, 100 customers as one, you know, one address or something. So is that the number of customers you have?

So there has to be one source of truth within the company. And that’s, you know, it’s not easy, and there’s lots of companies out there trying to solve that problem and get everybody to be consistent on that. But the reality is, it is chaos, and so it usually comes down to the finance organization having to come up with one standard answer, and that’s who we work with.

And then we had to put this in here. Your benchmarks are used for vanity. We, as I mentioned, became a were acquired by Bain. They own 100% of us, but we’re a separate company. But Bain and Company is a consulting company, but works very closely with private equity, with big investors and and also for any of us. I mean, I was at Softbank, and, you know, all of us have had some involvement with investors, with all the incredible hype in the tech industry, it’s pretty hard. Like anyone remember about two years ago, net dollar retention rate was, I think in a lot of ways, a vanity metric. Snowflake is doing 180% net dollar retention rate.

So net dollar retention rate is the measure of the net change in your cus in your contracts with customers. So if you have customer A in you know December 31 2022 and the value of the contract with that same customer A at the end of 2023 net of any churn, net of any downsizing, but also net of any upsizing, is what your net dollar retention rate is, very simply, and I’m going to actually come to a discussion here to talk about that. But you can’t keep selling your customers 180% increasing the contract in effect by 180% every year. Like, let’s be real. Not everybody does that. It’s great, and especially, and then it turns out that there may have been some, you know, starting the clock with a prototype. So, yeah, you start with a prototype, then you get to a real contract and increase it. That’s 180% right there, but it’s not going to happen the next year, or getting good benchmarks and not taking action. And that goes back to reinforcing what Claire said, which is, we hear a lot of great things here, but how are you going to take action and use this in your company.

So Ben Horowitz, great if anyone hasn’t read his book. I wish I had the name of it, but yeah, exactly. It’s such a good book. So what we see for the most part in 2023 and we’re working mostly with companies at scale, and I know a lot of companies here, early stage is focusing on margin expansion. It’s a nice way of saying margin improvement, or cost controls and growth efficiency. A lot of companies got a lot of money in 2021 and spent it on hiring sales people, and spent it on expanding and hiring. And it was funny. I think part of that, from what I heard from some of our CFOs, was because in 2020 everyone went into, you know, stop mode for the first six months, and then suddenly the second half of 2020 SaaS market was pretty good. You know, companies are growing, and suddenly they’re behind their hiring schedule. And then they went into 2021 and they raised some money, and they took a whole bunch of money, and now they had to hire all those new people for 2021 plus the people that they didn’t hire in 2020, and then they go into 2022, and suddenly everyone’s saying, Oh, my God, there’s a recession. Now what do we do? So it’s been a little hard managing through that or planning, but it’s working out.

I’m going to we already talked about rule of 40. So here’s just a quick example of some of the differences that you might see. So I took two companies here, 25 you know, a group of benchmarks for 25 to 50 million, high growth, 25 to 50 million, sort of average growth and big differences in this and I love these metrics, particularly when you think about planning for 2024 because head count has been the major cost for tech companies, right? It’s about 80 sometimes 90% of the cost of a tech company, but I’ve seen, because I’ve been doing this for 15 years, over time, the percentage of head count within a particular department going down. And what’s interesting is I tend to see really fast growth companies that percentage is lower.

So when I was running a sales organization 20 years ago, 95% of my expense was head count and or maybe 92% and a couple of percent on, you know, travel and expense, and then, you know, not much else, few tools. And then you start having salesforce.com and CRM and blah, blah, blah. But you see it increasing, increasing. And then now we’re seeing all these great AI tools that eliminate, you know, some of the routine work in sales, stuff that you know just copies everything that you you know. You just talk into your phone and your your input into Salesforce is all taken care of. Your manager communicates with you totally remotely, but so that costs money, so now that’s going into that bucket instead of the head count bucket, and same thing with R&D, just so much. Can be spent in, in enabling the productivity of your your people, and that’s if you take anything away, that is the direction that we’re going in.

So I’m going to jump into because I’m running out of time. I’m like, Bob here. Good thing you spoke first and were my model. I could talk about anything all day long on this.

So when you look at go to market, so the SaaS model is a complicated model. It has many more levers that drive it. It’s not traditional tech, traditional software companies, it was just income, statement, balance sheet, you know, sales, R&D, develop the product and then do some support have, you know, financial management of that process. SaaS is, you know, you have the whatever you want to talk about, the latest, you know, important thing in marketing, but effectively, sort of the funnel of getting prospects in. You sell the customer, then you work, keep the customer engaged, you make sure that that information is being fed into your product management and into your R&D, so that you have continuous innovation. And then you renew the customer. You try and upsell them. It’s a continued there are many, many levers. You have a subscription that you are recognizing ratably. It’s, you know, accrual.

You sell in December, you still have to manage that relationship for the next 12 months. We were having a conversation about two year contracts, three year contracts. You know, in general, I’ll say the best practice is, unless you’re early stage and you really just need the money and the cash flow, don’t sell more than a one year contract, because every company that starts getting to scale, they end up instituting a policy like that, Because longer term contracts tend to make your organization less customer focused. Oh, those guys, we got 100% retention with those guys, you know, because they’re on contract. So I’m going to focus on these couple of trouble makers over here. And lo and behold, your engagement goes down your you know, it’s just not a good sort of system for your company.

And then, because of that, you have to also focus on R&D, so magic number and R&D that covers about 80 to 90% of the efficiency of your company. So make sure you know that, because that gives you a sense of where things are going. And the reality is, couple months ago, there were lots of things out on LinkedIn talking about how sales and marketing expenses going down. Growth rates are going down. Well, we just ran this a couple days ago, and the correlation for the public companies, you know, this is from the Bessemer cloud index, is pretty tight between sales and marketing spend and growth rate, but that’s because these are really growth efficient companies, you know, they’re not just spending the money and not getting the growth. So you can’t look at it just as how much money. You know, if I spend the money, they’ll come kind of like, build the product and they’ll come. You do have to make sure you’re getting the growth for it.

So, and I’m sorry this, I know is a lot of small print. I just picked a couple of of metrics that we would look at. But we, you know, we do a lot and have lots more in sales, marketing and customer success. So I just wanted to show how important it is to get the cohort right. So what I’m showing here, I can’t even read that. It’s so small. You know, two same revenue sized benchmarks, 50 to 100 million, same sort of business model, both selling contracts around 100k but one is slower growth, one is faster growth. So one thing that I’ve noticed that is sort of counterintuitive is because I hear a lot of CFOs saying, Okay, well, total sales comp, you know, OTE, so quota has to be four, 5x OTE. Well, even from the same companies, I don’t really see it in real time. And so here you do have it, but that’s a slower growth company. I guess what I mean is, in faster growth companies, you don’t always see it perfectly like that, but what’s interesting here is they have a lower cost per head count. And I love averages. People, that’s the other thing about benchmarking is people get caught up in sort of the trees for the forest, like, well, what’s the right comp plan for, you know, hiring AES, or what are the right benchmarks for, you know, this position, and I always go back to again at the end of the day, we’re all cooking with water. So at the end of the day, what’s your average cost in sales? So it’s up to you to figure out what’s the right combination. Is the right combination a bunch of, you know, Junior BDRs, who are, you know, low cost, and a few really high cost AEs? What usually doesn’t work from an efficiency perspective is all high cost people. I’ll just say that offhand. So we like to look at sales productivity, we look at average comp for the whole organization, we look at the BDR to AE ratio, and I think that’s going to be really interesting over the next couple of years, because, you know, with productivity tools, with, you know, the whole world of sales has changed and evolved with the remote world that we’re living in. And then also cost to customer acquisition. You know, you always cost to customer acquisition is also something, again, I really counsel people not to over index on, like one number, so CAC is going to change over time. Yeah, definitely stay on, you know, track it, compare it to peers. Do cohort analysis within your company to see which cohorts of customers are cheaper to acquire or more expensive to acquire. Do CLV to CAC for cohorts within your company, so that you can then get the average CAC for your company always work back up to the averages, and that will drive the overall financials of the company. So marketing magic numbers. So this company, with a slower growth you can see, is under the point five that I talked about. They have to have a lot more marketing qualified leads in order to close one deal, same size deals, but so they’re probably spending more money on that, and then you can see they’re spending more just on comp and marketing. So they’re not using productivity tools. Their net dollar retention rates lower. They have higher customer retention, but they’re not up selling.

And what’s interesting is the other company also pays their customer success people more. And there’s different arguments about that, and that definitely depends on the model that you have. But my overriding goal here was to show you that it depends, you know you I can’t give you one benchmark that’s a perfect blueprint for one thing.

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.

If there’s anything you take away from this talk, it’s two things.

One is, get the cohort right, and the other thing is, don’t focus on one metric.

And I’ll say that with a caveat. We had a good conversation out in the break. I think if you’re an early stage company in looking for product market fit, then yeah, focus on one metric, number of users, number of the engagement level, whatever it is. But when you want to scale the company, you have to look at all the metrics together in a model.

So the other thing I just want to not, you know, I think there’s a lot of tech folks here, so I’m preaching to the choir, as compared to normally, I’m talking to finance people who are like, okay, as a company gets bigger, R&D goes down, right? You know, it’s scale, not necessarily, and it also depends on what’s interesting is the times. So right now, you have this generation of great SaaS companies that are billion dollar SaaS companies, and then you have the mega giants who are out there, and it’s a it’s a war, a friendly war, and so the big companies are actually investing a lot in R&D, and you know, there’s these loads of conversations out there about, do you have to be a platform? Is that the way you have to be? Or should you be a you know, niche app or whatever, but definitely, these guys are expanding. But they’re also getting more dollars of new recurring revenue for every dollar that they’re spending in R&D, which is pretty impressive.

So I only have a few minutes left, and I thought I would throw this out just as an example of going back to my original point, which is using industry best standards for calculating your metrics is really important and can have a big effect both on your ability to understand your company and also on how investors look at you. And you know, if you ever want to talk to me about there’s a million stories of people present their companies, investors now come in and they actually look at all your records, you know, at the system level, and they will do their own calculations. And if you’re not following standards, or can’t, you know, stand up to the numbers you put on your presentation, then you’re going to get a worse valuation or no money at all.

So here’s an example. Somebody signs a contract nicely on January 1st, so that it’s really nice for the accounting and $12,000 and then, exactly the middle of the year, halfway through, they add another module for $12,000 but because their renewal date is January, 1, you’re going to co term it for the next January. And so you tell them, you only have to pay 6000 you know, and then at January 1 next year, you’ll pay 24,000 so how do you calculate your net dollar retention? Did you increase that contract by 50% in that year, or did you increase it by, you know, 100% in that year, and then you didn’t increase it in January of the next year? So do you do it based on cash, or do you do it based on the contract? Does anyone want to? And I’m not saying, you know, there are people who would argue both vehemently, and then there are people who would argue it one way one year and argue it another way a year or two later. So that’s that’s not good. I guess another principle that you should remember is be consistent. Don’t change with the wind.

Lauren Kelley

Does anyone have any thoughts about how you don’t have to say this is how you do it in your company. But what you’ve heard from other people.

Audience Member

Does it depend on your cash or accrual basis for your business? Would that determine?

Lauren Kelley

Well, that could be a rationale, yeah. So, I mean, that is a great point, because typically, as companies get to scale, they move to accrual, and that’s I can speak to that as a founder of a bootstrap company that’s been, you know, a couple years process just to get everybody in the headset of accruals instead of, Wow, we did this deal. This is so awesome. So generally, it’s good to do it on the on the booking, but a lot of CFOs will do it on the cash. And, you know, the important thing is, what you don’t want is someone to go through your books and say, these accounts you did this on cash, and these accounts you did on accrual like now we have to give you a 50% haircut, because we’re only going this way. So it’s not, I wouldn’t say there’s absolutely a right answer, but the wrong answer is to change how you do it, or to do it differently for different accounts.

Audience Member

So I would do. My instinct would be, because they are as an internal number, not a gap number, right? It’s something I use the management it would be based on my aggregate churn rate. So if I have a high churn business, I might take one approach. If I have one where, hey, that ARR is really AR, that’s going to be there, I would, I would think of it the other way. Is that crazy?

Lauren Kelley

Well, it’s interesting, because you bring up, there’s really three ways of looking at churn. So this is net dollar retention, which is looking at your contracts and just how the value of the contracts. And then there’s customer churn, which is the number of companies, so nobody churned here. The retention was 100% of the customer, but it wasn’t more than 100% so the contract doubled, but the customer didn’t double. So that’s where it gets tricky. And then there’s a third retention rate that people talk about, or that we use, and everyone uses, is gross dollar retention. And gross dollar is just looking at your it doesn’t include your upsells. It just looks at, have you retained the value of that one contract? And again, I think you have. It’s a system. You have to have all three because what happens is companies get, you know, especially, I think a year or two ago, when everyone was like, focused on net dollar retention, we started seeing companies with even, like 60, 70% customer retention and and maybe that’s good, because you can go through a transition period where you’re just focusing on the customers that you can upsell, and those are the profitable customers, if you’re doing it intentionally, but if you’re losing a chunk of customers, but you are unaware of that because you’re only this other metric looks good, then that’s not good. And you might have, like, a whole bunch of sales people who are working with these customers that you’re losing, and that’s a waste of your resources, that you could be putting them over on the ones that are selling. So you have to know these things. I think it’s really important. But I think there were some other questions, and I’m I know I think I have five.

Mark Littlewood

And I’m going to say because I think there is an infinity of questions here, I’d be wrong. And if I ask you like this in public, I know you are super busy, and, like most people in this room, super high value. But would you come back and do a an online talk. So we’ll put the this talk up live, and then have like, a Q&A online sometime later in the year, early next year, to keep that going?

Lauren Kelley

Yes, if people are interested.

Mark Littlewood

Because I don’t think we can do the questions justice. I take it the applause means people are interested.

Lauren Kelley

I do want to put a plug in here for this is a great book that explains a lot of these things. It’s written by a CFO, but he explains things in a really easy to understand way, and really establishes a great framework, so I really highly recommend that, and you can get it on Amazon.

Lauren Kelley

So this is just, you know, we’ve gotten some these are companies that benchmark with us three or more years on an end. You know, over three years have gotten these kind of results, and obviously this Toots our own horn. So our marketing folks like me to say this, but more importantly, it works. People don’t apply benchmarking as a management process, and it really works, and that’s why the stats are compelling. So we can, we can use the other one for what’s on your 2024 performance score card and what metrics you’re tracking as maybe a basis for an online. Awesome.

Mark Littlewood

Votes all those in favor. (Applause)

Lauren Kelley

CEO & Founder, OPEXEngine

Lauren founded OPEXEngine in 2005 in Waltham MA to offer entrepreneurs, investors and enterprise software businesses access to reliable data and insight to inform their strategies, plans, budgets and scorecards. Her company became the industry-leading SaaS benchmarking resource based on audited, anonymized company data. In 2021 she sold the company to Bain Capital where it runs as a separate business she still leads.

Lauren’s held executive positions in some of the industry’s most successful companies, and having advised hundreds of forward-thinking technology businesses including Compaq, Borland and ATG. She has unique insights into the metrics SaaS organizations should benchmark against in order to grow profitable, high-value businesses.

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.