How many times have you wondered if your company has prioritised the work that will actually solve your customer’s problems? Not the ones they tell you about – that’s easy. It’s the problems that they don’t talk about that will trip you up every time.

As product organisations, we’ve developed any number of frameworks, techniques and processes to get at this elusive knowledge, and then to proritise it correctly. In firm after firm, Randy Silver has seen the same problems crop up – then he discovered a new technique that generates genuine insight in as little as two weeks. Instead of wondering if you’re committing your teams to solving the right problems, the Insider Insight methodology ensures that you’re asking the right question.

In this talk from BoS Europe 2019, you will gain an understanding of why the discovery process is broken – but also how you can employ a new approach to fix it that will complement your existing practices.

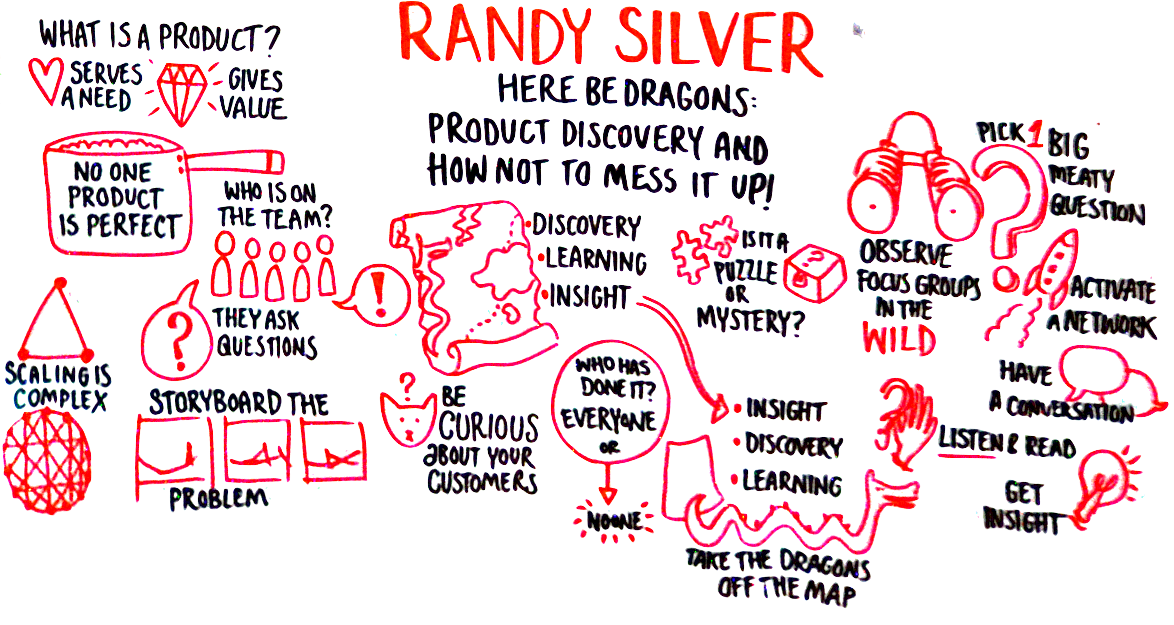

Find Randy’s Talk Slides, Video, Sketchnote, Transcript, and more from Randy below.

Find out more about BoS

Get details about our next conference, subscribe to our newsletter, and watch more of the great BoS Talks you hear so much about.

Video

Slides

Sketchnote

Transcript

So I realized I’m the only thing between you and drinks. So I will keep this reasonably short, I hope.

So first a quick introduction, among other things, I host a podcast called the product experience. It’s given me a great excuse to call up some of the smartest people I’ve met, or have yet to meet, and ask them about how to do my job better. It’s an absolutely fantastic thing to do. For the last few years, last 10 years, I’ve been a head of product at various places. I’m now working as a consultant, and working with an agency out of New York called Motivate Design that teaches people how to do discovery better. And when I first heard them talk about it, I thought it was the most incredible thing I heard. But that won’t take an hour. So I’m gonna talk about a few other things. And then we will come on to that.

What I do want to talk about today is: what is a product? What’s a good product? What’s a product team? And how do we work together to make good products? So just to get a sense of the audience? How many of you are either product managers or work closely with a product manager? Fantastic. Okay, so this will be somewhat relevant so that’s good news. Okay, so first, so my favorite interview question to ask when I’m when I’m meeting people: you’re a product manager, what is a product? You’d be amazed at how many people can’t answer that question very well.

What is a Product?

So there is a business school definition, it’s very long and very boring, and we’re going to ignore it completely. So my definition is a little more concise, it’s something that can be a good and idea method, information, object or service. If you want to have the product versus service debate, I’ll be in the pub later, I’ll be happy to do that over drinks. But it’s something that serves a need or satisfies a want. It’s hard to say that Candy Crush serves a need. It definitely helps me when I’m bored. But you know, it is still a good, a perfectly valid product. And it has to yield enough value to justify its continued existence.

I used to use the word profit. And then I realized that wasn’t quite right. Because there are internal products, there are nonprofit products. Profit and value should be interchangeable from this perspective. It’s whatever you realize whatever value means to you.

But how many products is your phone? To me, it’s one product. But how many product teams did it take to make this, you’ve got the hardware, you’ve got the software, you’ve got the system OS, you’ve got all this base apps. It’s not one thing. When we organize companies and we organize product teams, it’s really complicated. It’s very hard for us to figure out what the right way of putting that together is. So that we’re optimizing people to understand that your product is not necessarily the product. What the customer experiences is the product. So the definition of a product is dependent on your experience, because if you’re making the phone, you’re concerned about each of those individual components. But if you’re just the end user, the end consumer, you just want the whole damn thing to work. So perspective really matters. And we’ll come back to that a couple of times.

What Makes a Good Product?

So what makes a product good. There’s a podcast I really like called gastropod. Run out of the states. And they did this wonderful episode, where they talked about the perfect pan. How many people like to cook? Right, so the perfect pan must heat evenly be nonstick, lightweight, conductive and durable, I would buy that pan. Problem is to achieve that the ideal pot would have to be very, very thin and very, very thick at the same time. Which is why we don’t only have one pan in our house, there is no such thing as the perfect product most of the time. It is something that solves a need or satisfies a want at a specific moment in time. And sometimes we try too hard to over engineer things and try and make a perfect thing instead of a suite of things that serve the needs.

What is a Product Team?

So what is a product team? How do we go ahead and create that one perfect product or that suite of products? The thing that is relevant to you at the time. So a product team, I think, is a group of people like a product that fillss the need or serves a purpose and delivers value for the organization. And that’s fine. So who’s on that team? I worked for a place that decided it was this: four devs, two QAs, half a scrum master and one product owner or manager. That’s not a product team. That’s a team that will hopefully, presumably, give you functioning code. Functioning code is not, in and of itself a product. So we do add on lots of other things we add on UX and copy and security and marketing and sales and service. And sometimes, if you talk to other companies that think about this, and from a greater perspective, they’ll add people like bankers and lawyers, if they’re TransferWise, because that’s their job is opening new currencies. And they can’t do that without having that expertise on the team. Babylon health has a doctor as one of their product managers to make sure that they have the right expertise. When I worked at Sainsbury’s, we had store managers that would sometimes come in and sit with us. That doesn’t mean that all of these people are doing all the agile ceremonies that we talk about. They’re not necessarily getting JIRA tickets. God forbid somebody in marketing gets a JIRA ticket. You know, they’re not necessarily coming to stand ups every day. But they understand that they’re part of the team, they understand what the mission is, they understand that we’re all working well together. So the team isn’t necessarily the people who are there every single day, it is the people who understand the mission of putting together that product.

So how do we actually create that? Let’s go back to base principles. What is the product team? So being a bit more philosophical about it. I think it’s a group of people that can ask a question. It’s kind of key, if you’re going to do product development, you have to first be able to ask a good question. And we’ll talk more about questions in a little bit. And what use is asking a question, if you can’t get an answer, even when we’re more worrisome, you have to be able to understand the answer. And that’s something that we don’t spend enough time on very often. And finally, it’s great if you’ve gotten to this point. But then you also have to be able to take action based on it. And that’s having the resources to do it, having the permission to do it, and having the support to the organization to go ahead and do it. This is hard. This is really hard for us to do. We put a lot of bureaucracy and a lot of things in the way at most companies that don’t allow us to actually create a fully functional product team.

And Marty Kagan has this great line, “if you’re just using your engineers to code, you’re only getting about half their value. “I’m sure most of you’ve heard this before. But it’s not only applicable to engineers, it’s applicable to everybody else. If you’re only using your marketers to market if you’re only using sales to go and do outbound things. If you’re only using support, to take calls and try and fix point point issues. You’re only getting half of their value as well use everybody. They’re all invested in creating a great product. They’re all part of the team. And it’s hard. Like I said, my friend Janet Vasco says people are hard. She’s talking about soft skills here. She her point is that what we call soft skills are some of the hardest things that we do. She’s absolutely right, people are hard. What’s even harder than people, though, are lots of people. So lurking at scale is a real challenge. When you do this, you start to pricing Metcalfe’s law, you start to introduce more people more nodes, the lines of communication get really difficult. Getting everyone to stay on the same page is hard. By the time you get to 14 people, you’ve already got 91 lines of communication to try and keep aligned. That’s really difficult. Anyone who’s been at a scaling organization knows how hard this is, it’s easy when you’ve got five people in a room, it’s hard when you get a much larger organization, or when you start going to multiple locations. And on top of that management structures, now we make it even harder for the people to talk to each other even if they want to.

So all of this is hard. I’ve been playing around with the new definition of product managers. I think a product manager is ultimately the one person in the organization whose job it is to fight Conway’s Law. Make sure that we don’t ship the org chart that the customer is the person who sees a seamless end to end experience, regardless of what we all do internally. And we make a fundamental mistake a lot of the time; we forget what the product is. We think the product is this thing in the middle, we think it’s the flower. That’s not the product.

The product is Super Mario. You want people to feel empowered people use your product because it solves a problem or fulfills a need for them. What you serve them will change over time if you want to have a continued relationship. What’s important is that you keep making them powerful. Just don’t concentrate on that. Don’t worry so much about what’s in the middle. Don’t feel too attached to it that will change over time. So how do we create value?

How Do We Create Value?

Well, it’s a technology conference, and no one has mentioned Steve Jobs today that I’ve heard. So an obligatory story. So when he bought Pixar the story goes that he went down to Los Angeles and said, I know nothing about the movie business. And he asked a friend of his, “What makes a good movie? How do I do this? How do I run a movie company?” And the answer that came back to him is, if you have a good story, everything else will work. But if you don’t have a good story, nothing else is ever going to work. And there’s a great story about Pixar that when they get to a certain point in the development cycle, if things aren’t working, they send everyone home critically, they also keep paying them. But the brain trust gets together and make sure they fix all the problems with the story. It’s only then that they bring everyone back and they continue production. So they do this because they do minimum viable products. They do animatics they do storyboards.

We do this too. This is exactly what we do. We do this before we get someplace. We do things like paper prototypes, we do smoke tests, we do Wizard of Oz tests, we do all kinds of different things during the product development cycle, we have to make sure we get it right. But critically, we have to make sure we have the story, right? We have to know: what is the problem we’re solving for our customer, we have to know that the customer actually cares about it, and that they’re going to use the solution that we think that they should.

Discovery.

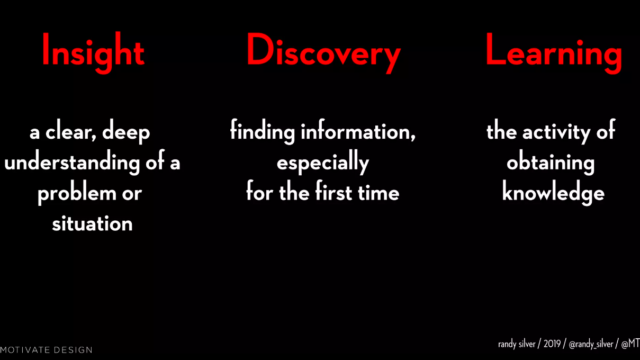

So now let’s spend the actual time talking about discovery. This is the title of the talk, we should spend some time on this. So how do we know when we’re done with discovery? Does anyone have a good definition? I usually know I’m done with discovery, when I walk into a room like this, and someone in the more expensive shirt says, “You’ve spent a lot of money. What am I going to get for it? And when am I going to have it?” That’s a terrible way of doing discovery. It’s absolutely awful. It doesn’t actually mean that we’ve got an answer. It just means that we’ve run out of time. And that’s not the right basis to make a decision on, not if you’ve got a choice. So what is discovery? If we don’t know that we’re doing it? Well, what is it actually? So it’s the process of finding information, especially for the first time. And we used to represent it on maps like this. And we put in dragons, and we put in whirlpools, and we put in danger. And that was really relevant. When doing discovery meant you weren’t sure that you were going to come home. I don’t know about you. But I haven’t had to wear any specialist equipment. And I haven’t had to worry about whether I’m going to make it home during the discovery process. So it’s not quite as accurate today, but it’s not really discovery if other people already know the answer.

Just because you don’t know it doesn’t mean it’s not discovered. I’m American, so I grew up learning that in 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue, and he discovered America. This was a huge surprise to the people who already lived there. He also never actually made it to the mainland, he only made it to some of the islands. But putting this in product terms, he learned about a new market opportunity. And he exploited the hell out of it. And from the perspective of the people that were living there, they learned an awful lot about new people, new technologies, which generally weren’t shared with them, and new diseases, which unfortunately, were. But most of the time, we aren’t actually discovering anything we’re learning. So learning is the activity of obtaining knowledge. We do that a lot, we’re actually really good at this. We have a lot of frameworks and a lot of techniques that help us take a hypothesis and review it and refine it and get better and better and better.

But obviously, this slide is designed so that there’s a third thing. And I think that insight is: you can’t do discovery or learning until you have started to empathize with what’s going on, until you really understand from the inside. What do your customers care about? What is the opportunity? So, a clear deep understanding of a problem or a situation. It’s then that you can go into the discovery and learning. So it’s cycle. Why do we do it though? Obviously, we do it because we want to know what to build. But there’s some other really good reasons. Teresa Torres is a fantastic discovery coach out of Portland, Oregon. She says the day we stopped being curious about our customers is the day our competitors start to clean up. And she’s absolutely right. And I could not say it better. So I just quoted her. There are the reasons though, there’s also the cost to change. So we know this ‘time versus money’, and ‘waterfall or scrum fall’, as time goes on, money goes up, cluster changes. So, this is really hard. We know this, we’ve tried to do better things. Not everyone always believes in them. My friend James has this great line when executives raise the concern that Agile is making it up as you go, it doesn’t hurt to remind them that waterfall is making it up before you’ve even started. So we were promised agile, agile makes everything better reduces the risk. That’s what we were promised by it anyway, the reality, at least in my experience, is that it goes a little bit more like this, because at a certain point, complexity comes back in and it starts to creep up again. If we did everything right, if we were able to continually reduce our risk back down to zero, then we would be able to keep the cost at a relatively low basis. But we tend to get bad at this as time goes on.

So this goes back to the dragons. These are the unknowns that we’re dealing with a lot. Now. It’s that cost of change. And we deal with that a lot by things like OKRs, objectives, and key results and making bets. And we’re not always very good at them. But we try this. One of the best things I’ve learned about in the last year that Teresa Torrres did in around 2013, I only learned about it recently. It’s a different way of doing estimation with your teams and it’s very simple. If everyone in the world has done this, we know exactly how long it’s going to take to do. If lots of people have done this, including someone on our team, then we have a pretty good idea of how long it’s going to take that person to do it. But maybe it’s important that they teach other people on the team how to do it. So we know how long it’ll take one person, we don’t know how long it’ll take them to teach and for other people get it. Someone in our company has done this, or we have access to the expertise but when are we going to get that access? How much time do they have to devote to help us to do it? We have reasonable amount of confidence that we can do it, we’re just not always sure how long it’s going to take. If someone in the world did this, probably another company, a competitor did it. Again, we know it’s possible, given their circumstances, we don’t know that it’s necessarily possible for us. But we have a reasonable bet that we could do it as well, if nobody in the world has ever done this before. And you’re being asked to give an estimate of how long it’s going to take and what it’s going to cost. You’re not going to be in good shape.

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.

So we’re very good at this discovery process of talking to certain people. We talk to customers all the time, we talk to subject matter experts, we talk to each other, we talk to the people in the room. And they give a certain perspective. And again, that’s that perspective order. It’s really important. And I grew up playing baseball and standing at home plate in the middle of the field, with the pitcher about to throw you the ball, that diamond looks like it’s the entire world. It looks incredibly expansive. And a lot of times, that’s what we’re doing. We’re talking to the customers, the SMEs and each other and it looks like the entire world. But what if we’re not actually playing baseball? What if we’re playing cricket? We’re missing out if we have this perspective on all our prospective potential customers, and all the sales that we could be having all the people we don’t normally talk to? How do we know about the problems that we’re not solving today? How do we know what the opportunities are? And how do we generate confidence that we’re going to solve them the right way? So how do we get to insight?

Barry O’Reilly’s got a new book out about unlearning. One of the ways we get to insight is we have to throw away the way we’ve done things today, actively engaging in taking in new information to inform effective decision making an action. This is hard. It’s really hard to do. It’s why Barry wrote a whole book on it. And there are a lot of things that get in our way, a lot of biases. And I could do a whole talk on biases. I’m not going to do that today because Cindy Alvarez did a fantastic talk last year about this.

My friend Mel works at Conde Nast. And she has a great line about when we’re going into the discovery phase and she wants to know: ‘are we doing a puzzle? Or are we trying to solve a mystery?’ And the difference is, with a puzzle, we have all the pieces already. Hopefully we have the box and we know what the end result is supposed to look like. We know what good looks like. It’s just a matter of assembling it. That can be really difficult, but we know that there is a possibility of doing it with a mystery. We still don’t know what The Answer is, we don’t know what good looks like too much of the time, we don’t go into something, deciding whether it is a puzzle or a mystery.

Mitigating Risks.

So, now that we’ve laid all the groundwork for this, let’s bring on the dragons. Let’s figure out: how do we actually do discovery in a way that mitigates these risks? So I mentioned earlier, I’ve started working with this agency in New York called Motivated Design. They have a technique that I heard about late last year called Insider Insight. When I heard them talking about it, I said, “This is brilliant. I want to do this, why aren’t you doing more of it in the UK?” And they said: “Would you like to give us a hand with it?” So that’s why I’m here to tell you about this technique. This is not a sales pitch, because I’m going to tell you exactly how to do this, the technique.

So the precedent, the thing we’re supposing in this is: where do the conversations that your customers are having – or your potential customers – happen? They happen in the wild. And we want to go out into the wild, and observe our customers and potential customers and find out what it is that they’re talking about. What kind of problems that they have. But most of the time, we don’t go into the wild. We’re going to the zoo. And we’re demanding that these animals perform for us in this artificial environment. When we show up, when we want to be there, this is what we want. But then you notice there’s a chain link fence behind them. This is not where we’re going to see genuine behavior from our customers. When do we see it, we see it when they spend time with each other, with their peers in an actual environment.

Now, sometimes we do ethnographic studies. But it’s expensive. And it takes a long time. And it’s really hard. People reveal the real answer to their feelings to what their biases are, what their likelihood to do something is, what their problems are and how they want them solved with each other and with their real life connections. With people like this, you’re much more likely to talk to a friend or a family member than you are to me in a focus group environment. It doesn’t matter how well trained I am, how good I am at asking questions. It’s an artificial environment, there are things you’re never going to tell me. So this is why we do this. It’s powered by connections, and crafted by conversations.

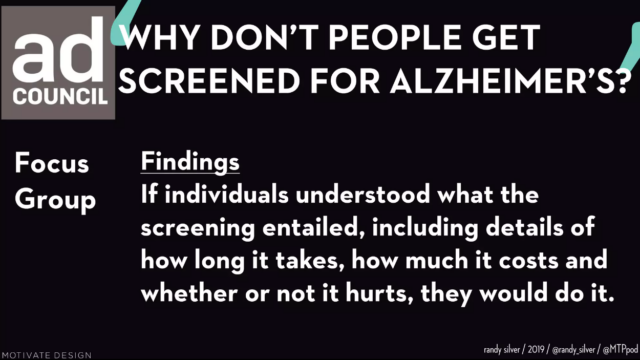

So I’m going to give you an example. This is the first example I heard about the technique. And this is what convinced me. We were working with the Ad Council in the United States. And they were doing some work with the Alzheimer’s Society. And they want to know: why don’t people get screened for Alzheimer’s? And they ran focus groups in multiple cities, it took quite a long while and it was expensive. And they found out some really interesting things. People didn’t know that it was non invasive, they thought maybe you needed a brain scan. We don’t have the NHS in the States. So they thought they might have to pay for it. They didn’t know that it was free or covered by insurance, that you know how long it would take. That was fairly easy. You find this information out.

There’s a fairly obvious next step, we’re going to run an awareness campaign, we’re going to tell everyone these things. We’re going to educate them on how easy it is to get a screening. But we talked to him and said, “Actually, we’d like to try this new technique with you. So let’s try insider insight. And let’s see what happens.” So, like I said, focus groups took months, this took two weeks. And we found initially the same thing: whoa, awareness of the process. So great. In two weeks, we learned what took you three months to learn last time. That’s pretty good value in and of itself. We learned more though; we learned what the people actually told their family members and their friends. They said things like the symptoms are the screening. It’s not a disease, it’s a disability. And I don’t want to know. How do you fight that with an awareness campaign? And when someone says something like this, why die twice? That really brings it home? If you have a persona already, or if you don’t, this makes your persona. Even if we don’t know what the right answer is. We’ve just saved you hundreds of thousands if not millions of dollars on a campaign that isn’t going to convince anybody.

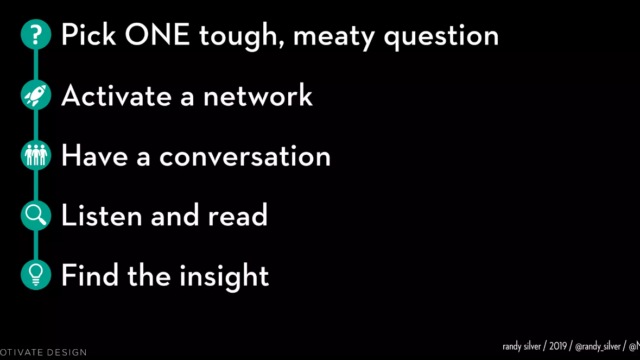

So now you can focus on the right answer. No discovery process is ever going to promise you a definitive answer. But we can promise you a better question quickly. So how do we do it? So first, pick one tough, meaty question. And we can lean totally into bias on this. It doesn’t matter because people exhibit bias in their real life purchase decisions. They have a lot of emotion. So you pick one really tough question. And it’s not these questions. These are the types of questions we ask a lot and they generate didn’t answer. And that’s interesting. These are good questions to ask at a certain point in the cycle, you want to know how big your your market size is. You want to know if people find your app usable. That’s good, but not at this point in discovery. At this point you want to be asking questions like this. If you’re a bank, you want to know: “What do young adults struggle with?” When planning for financial success after university. If you make baby formula: “Does formula mean you failed as a mother?”

But you ask these questions because they generate insight. They tell everyone in the organization, what it is that your customers and potential customers are actually thinking. It allows you to get rid of the biases that you have about: we already have the solutions, we already have the knowledge and we know how to solve this, we’re just going to use the things that we have and packaged them differently. Or, we’re going to build this cool thing that I want to build. This allows you to understand what is it that people actually want or need. And we’ve done this with a bunch of different companies. We’ve done it with Facebook and Verizon, Nike and Skip Hop. We’ve asked a lot of good questions. There’s a whole bunch of other customers we’ve done this with. And I will share the slides later. So you can read all of this later.

But let’s get back to the technique. So like I said, pick one tough, meaty question, something that’s going to generate real conversation. And it’s not that easy. There are more steps. Next is activated network. So we have this global network, we’ve got just over 2000 people in something like 40 countries. Now, these are not the people we ask a question to. They’re interesting people, they are UX people, they are product people, they are researchers, but they’re also social workers, and they’re cops and they’re teachers and they’re nurses. These are people who are driven by having good conversations and getting to truth. They like to understand and really dig deep into things. And we screen these people, we make sure they’re qualified to join our network in the first place.

So we take a mission, we come up with a question, we come up with a target persona, and then we go to our network. And we say we want you to talk to someone that you know, that fits this profile, and have a conversation on this topic with them. That’s interesting, because the people that they have access to are far better than anyone you will ever recruit into a focus group. You don’t want people who go to focus groups professionally. Just think about your parents, your cousins, your friends, your family, your co workers. These are people who have fantastic insights, who will generate a great conversation and you know that you can have a really interesting conversation with them. I’d much rather hear you guys talking about it, than sit in the zoo, and try and get somebody to open up about something very personal, and tell us something really considered. So activate that network, get them to reach out to people in their network to talk to, we will pay both sides. And that’s one of the key things. But it’s not a lot of money. It’s enough for dinner or drinks for both sides so that they feel like they’ve gotten something out of it. They’ve been renumerated for their time. But these are not people that are driven primarily by money, let them have the conversation.

So for the smallest version of what we do: we turn it around in two weeks time, we need 10 conversations. So we commission 12 or 13 realistically, because we know not every conversation is going to be perfect. Some people will drop out. But let them have the conversation and have them record it. In some very specific cases, the question that we ask is very sensitive, in which case we don’t record it. And there’s a slightly different process, which I can talk about later on. If you’re interested, but 99% of the time, there’s no problem; we can use your real name, we can use an alias in the after action report. But we get the recording. And the recording is really great. Because not only do we get a transcript of it, but we hear the emotion as people talk. And if you’re not going to be in the room for an interview, you want to really be able to understand it and experience it as closely as possible. And then we get that recording back. We get it transcribed. We listen to the recordings, and we read and we do a normal synthesis. Same thing you would do with any type of research or discovery activity. And then finally, we find the insight. That’s not true. Actually, we don’t find the insight. In our case, we’re an agency. We don’t know your customer nearly as well as you do. We don’t know your market and potential customer as well as you do. You find the insight. We tell you the stories that we’ve heard, we hope you understand it. But the insight is something that has to be generated internally, the internal agency model of having an Insights Team fundamentally doesn’t work from this experience because there’s not a golden tower of people who can come and get knowledge and just tell you what the insights are. Insight is an emergent property.

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.

So with apologies to you Rich Mironov, you don’t actually need to talk to customers, you need to listen to them. And I know Richard always talks to his product managers, and says, “When’s the last time you talked to a customer?” Hoping I can get you to change that to be listen? This is the key thing. Obviously it’s always good to talk to people. But the most important thing is to actually hear what the other people are saying. Talking can be a tick box exercise, listening and engaging with them and understanding them. That’s the critical thing. That’s what we all want to get out of this.

So we talked about quite a few things here. We talked about: What is a product? What’s a good product? What’s a product team? How do we work together? To talk about one last thing quickly. So I’ve been a product manager for a long time now. And my favorite dinner party conversation among product managers is: how do you explain what your job is? And I used to be really facetious about this, I used to tell my wife, “I go to meetings so that other people can get work done.” And that’s true, I absolutely do way too much of that. But that’s focusing on outputs instead of outcomes. And I want to focus more on outcomes. And a friend of mine had a much better one, and I’m stealing it’s completely. My friend Monica says, “We help people make better decisions faster.” That’s really what it comes down to. This is what we all try and do, product managers, product teams, try and help everyone else make better decisions as quickly as possible, reduce the risk, reduce the cost of change, we then obviously need to deliver on it. But if we’ve made the right decisions, everything else goes better. So the way we do that is by generating insight first, then going into the discovery and learning. The reason you do this is insight removes the dragons from the map, so that you can do the rest of it. It makes it safe to go and do discovery and learning. Everyone knows what they’re trying to do, and where they are in the process.

I do think we have a terminology problem. Sometimes I think we use the word discovery to mean way too much. And it’s worth breaking it down into those three components and know where you are in the cycle.

And finally, what’s the definition of success for this? How do you know that you’ve actually succeeded? We still have to face the problem that we don’t know if we’ve got the right answer. So there’s a couple of different things. One is how you work together as a team. Last year in Hamburg, I saw Jeff Patton do a fantastic talk. And one of the things he talked about was a way of constantly getting a team to concentrate and work together better. And this is a normal scrum board. We’ve all seen this before.

There’s a column here that I’m going to point it out. It’s this last one over here. It says ‘goal.’ For every swim lane, it says “What is it that we thought we were going to accomplish with this? How do we know that we’ve succeeded?” Our definition of ‘done’ too many times is that we’ve moved all the tasks over and move them into production. That’s not done. Done is when you’ve observed what that achieved. If you thought you’re going to achieve 5% lift in something, 3% deficit in customer issues, whatever it might be, whatever the metric of success is, until you observe it, you’re not done. As long as that’s still the business priority. If you haven’t achieved it, just take down all the tasks and start again, keep working on it. Because then that’s how the team, that greater product team, not just the devs or the QA or the product people, the scrum people. That’s how legal and support and marketing and sales and everyone else understands that you’ve succeeded, when you’ve hit that metric of success. It makes it really clear to the entire organization that you’ve succeeded on what you’re trying to succeed on. And this is the final bit when your stakeholder or your customer is this happy when you walk to the door. That’s when you actually know that you’ve succeeded. Because no metric can measure that. Metrics are a lagging indicator. This is one hell of a leading indicator. Make sure that your customers are this happy, your stakeholders are this happy when you come see them. Thank you very much.

Mark Littlewood: Thank you, Randy.

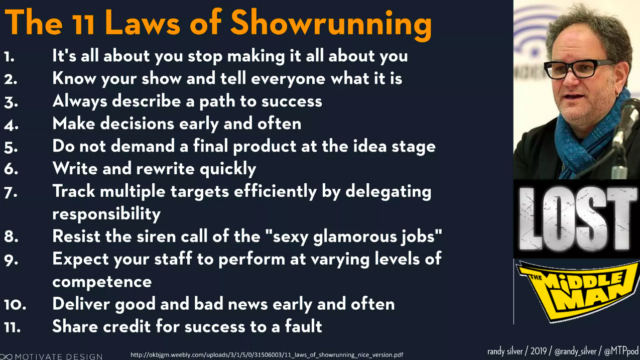

There was one thing I was inspired by this morning that I didn’t get to share, which is the best book that I’ve read. It isn’t a book actually, it’s an essay. It’s only about 25 pages. It’s fantastic. And it’s free to download. It’s called the 11 laws of show running. From Javier Grillo-Marxuach. This is absolutely fantastic. It’s all about running a TV series rather than product development. The only functional difference between what he does and we what we do is the minute an episode is finished, he doesn’t have to support it anymore. But everything else about the product development experience about working with a team of people to decide what the story is, and how to start working, and then how to work with other departments. He’s a professional writer. He does this brilliantly. It’s well worth checking out. Great. So with that, thank you very much.

Find out more about BoS

Get details about our next conference, subscribe to our newsletter, and watch more of the great BoS Talks you hear so much about.

Randy Silver

Randy is a recovering music journalist & editor. After launching Amazon’s music stores in the US and UK, Randy’s worked across a plethora of areas: museums and arts groups, online education, media & entertainment, retail and financial services.

He’s held Head of Product roles at HSBC and Sainsbury’s, where he also directed their 100+ person product community. Randy is Motivate Design’s UK Director for Insider Insights, a new approach to the product discovery process. He’s also a Product leadership consultant and the co-host of Mind the Product’s podcast, The Product Experience. Randy has been working as an interactive producer & product manager across the US & UK for nearly 20 years. (Yikes!)

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.