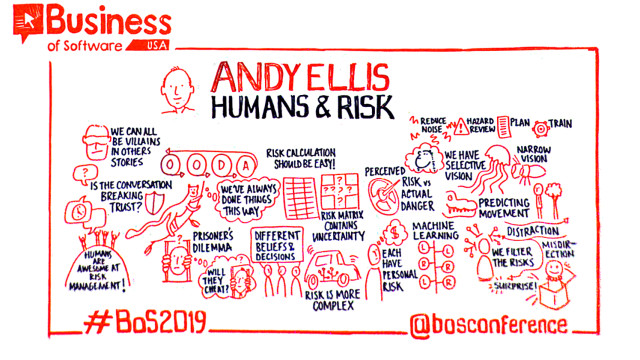

Andy Ellis, Akamai

Humans are horrible at risk management! How are we even still around? We’re now the dominant species on the planet. Why? How? Andy shares his thoughts on why humanity has significant advantages in making rapid, generally correct risk choices.

You will learn:

- How risk choices that appear unreasonable from the outside may not be.

- To identify the hidden factors in someone’s risk choice that most influence it.

- How to help guide people to risk choices that you find more favorable.

Video, Slides, Transcript, & Sketchnote below.

Video

https://businessofsoftware.wistia.com/medias/ra3xbn231w?embedType=async&videoFoam=true&videoWidth=640

Slides

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.

Transcript

Good evening. I promise that’s the only logo you’re going to see for us. I’m going to talk a little bit about humans and risk and how humans make risk choices and risk decisions because it’s really important to, basically, my core discipline. My job is basically to tell people like you what not to do, while you’re hell bent on going and doing it in pursuit of all of the reasons you’ve been hearing so far today.

And what often happens is we try to understand why people make hard decisions. So, I’ve been on this side of this conversation a lot. It looks something the product owner comes and talks to their security professional or maybe their lawyer or any sort of staff function whose job is to provide advice. And when they have that conversation something very interesting happens, those two people aren’t actually in that conversation. What’s in that conversation is each one’s representation of the other one. Every word someone says is not coming from them, it’s coming from your belief about who they are and what they think. So, they each have this caricature of themselves and these caricatures basically have a little battle with one another. You know the product owner says one thing, and the security person nods their head and hears something entirely different. For those of you who’ve been married or have children or basically interact with any other human beings on the planet you’ve probably experienced this at one time or another.

Villains

But what’s really fascinating about this is that because we’re interacting with a caricature – and it’s not a charitable one – we generally think less of our partner than we do of ourselves. We get to create this sort of white knight of ourselves; we’re the hero. And they’re the villain. They’re the one trying to do something horrible and so when they say something we go “aha! How can I defend that? Because I’m the hero I can do sketchy things back in their direction and that’s totally ok.” Thus, reinforcing their belief that we’re the villain. And so, when we say something back to them maybe in a snarky tone of voice or that is actually just snarky, they hear that and they go “aha! I’m dealing with the villain that’s okay; I can now be mean back to them.” If you’ve gotten into Facebook conversations about politics this is basically how it goes.

But what often happens is that we’re telling the story about the other person being a villain, yet we ourselves will do the same things to them. My favourite thing to challenge security professionals with when I speak at a security conference is ask them how many of the things that they tell their partners to do, they themselves ignore answer generally all of them. Because we have modal bias. If you are a driver how many people drive. At all. What do you think about pedestrians? They suck right? Generally trying to get themselves killed, believe they own the roadways. How many of you ever walk in a city? What do you think about drivers? They suck.

But what’s fascinating is like you can be driving and you’ll think nasty thoughts about pedestrians. You park your car you step out you’re like that horrible driver just tried to run me over, like you will shift in a moment. Between these two modes and your preference the one that you’re currently in. And so often we have a business conversation you may have seen one like this if you work with a security professional, the business owner comes in and says look I have this project it’s I’m told I have to bring it to you and ask if it’s safe. And what the security person hears is ‘I have a very dangerous plan. It’s going to ruin the business. And there’s dangerous things where you will kill the people with this like chat system we just built. So, can you please sign off on it. So, I don’t have to feel guilty about it.’

So, the security person says aha I have an ISO 27002 checklist – for those of you who’ve never experienced this, imagine a checklist of the things that everybody should have done, for every security problem, ever. So, we had a problem. We wrote down do x. Great. We won’t have that problem again. And we just keep adding to this list it’s hundreds of items long for systems that no longer exist. We’re still replicating the mistakes that we think they shouldn’t have made.

Now if you’re a product manager you look this, you’re like Oh my God this is just make work. I have to fill this out. Why do you exist? Fine. You know maybe could you just explain some of these words to me? What is the system level object? I kid you not that’s actually a keyword out of the PCI data security standard that you have to meet if you take credit cards that is not defined. It is not a term of art in security or systems. It’s literally just there so that when you get breached, Visa can say ‘aha! You weren’t doing system level objects right. It was your fault you were breached. Not us for having an incoherent standard.’ The security person thinks this is actually because you don’t care about security because you don’t know what our buzzwords mean. Even though we make them up faster than you do. So, we offer to fill it out for you. Now, conveniently this gives us more work to do so we can have more budget. That’s just a side effect. But it doesn’t really build trust at this point. All right we’re getting into the cycle where nobody trusts the other person and everything we say makes it worse. The product owner at some point is like Hey are you done yet? I need to go launch, and I need your check off here. And with the security person hears is it you don’t care about security. You just care about schedule. So, we respond with some incoherent requests could you use chacha20-poly1305. That is actually a real recommendation. All of you should be using chacha20-poly1305 in your SaaS applications.

Not joking.

You probably heard that and said he’s just trying to demonstrate that he’s smarter than I am. I’m not, because if I was, I wouldn’t do that. That’s a pretty ugly conversation that’s going to keep happening. And so, you’re just going to finally say look is that a showstopper. Can I launch or not? That’s all that really matters at this point. It’s too late to make any changes. And what we really hear is you are going to launch. This is not a real question. And if we you know say yes, then you’re going to ignore us, and you’ll ignore us forever and if we say no. Then you’re going to blame us when something goes wrong so let’s make a recommendation and you’ll hear that correctly as us covering our rear ends. Nothing really happened positively here. This wasn’t a good conversation. The product owner did not learn anything about risk. In fact, if anything they had to hide all their risk.

Risk

Reminded me of a conversation I once had with the CIO of Bechtel and we were at a conference and they said look we want to put a CIO and the CSO on stage and let them say all the things they wish they could say to each other in business but we’d better get ones from different companies. And he’s sitting there and we ask what is risk? And he said to me

“Risk is anything that impacts my schedule or my budget.”

Then turns to me and he says,

“You, sir, are risk”.

All you did was waste time and money here. And now what happens out of something like this is you’ll do a thing that your security professional thinks is bad. And so, we have beliefs about how humans are at risk management is everyone familiar with the trope of Florida man? Those of you from the UK? You are? Absolutely great. So, give me some words fill in the blank. How do we think about humans and risk management? They’re pretty bad at it. This is actually crowdsourced words I didn’t even come up with these on my own.

But fundamentally we believe that humans are awful at risk management and we have lots of evidence to support that claim. But I disagree. Humans are awesome at risk management and that will give you the only piece of evidence that matters. We are here today as the dominant species on this planet. We made some good risk choices to get here. So maybe we should understand how we make those risk choices if we want to improve them for the future because this isn’t like we’re have some God pulling our puppet strings to make us make good risk choices, like we happen to be here today. That can always change.

OODA

So, it uses a model John Boyd’s OODA loop. He was an Air Force fighter pilot who used this model to talk about how humans make decisions usually in an instant. I found it to be very helpful. It’s really important we talk about how humans think or make decisions that we understand the difference between science and models. All models are flawed. Some of them are useful. Understanding where the flaw is, is very helpful. So, through this I’m going to reference a lot of neuroscience cognitive behaviour except that I’m simplifying everything as models because that science is a wicked complex and that is not my personal discipline. So, in the OODA loop you see something happen.

- You observe

- You put that observation in context. You orient.

- You decide what you should do with this change in the world.

- And then you act.

Seems pretty simple. Now when we’re raising our children there’s some things that we like to know that they demonstrate that are helpful for us to think about. Observation is the skill of attention. Can you notice what happens in the world? Orientation is about processing; how quickly can you make that information fit with your model of the world? Decision is about executive function. Which we wish most of us would have more of but the ability to actually decide to do a thing rather than just sit and move on. Action is about coordination. It is about imposing your will on the world. It’s not just your manual or physical coordination. It’s deciding to do a thing and actually doing it. So, I started with this concept that we think people make bad decisions. We’ve all heard that before and I posit that we use the word bad or synonyms because we’re fundamentally polite human beings. We don’t like to say the word we’re really thinking about. We think people would make stupid when they make these decisions. We get a little joy out of mocking other people’s stupidity because it does make us feel smarter if I go back to my earlier slide.

But when we say somebody is in this state, it’s really because that decision is incomprehensible to us. So, the easy answer is that they must be stupid, or they wouldn’t make the decision because I wouldn’t have made that decision and I’m smarter than that. And I think the problem here is that we have a hard time putting ourselves in someone else’s shoes to understand why they’re making the risk choices that they make. So, let’s think about the models I talked about orientation being a model problem, and models are out the context the framing and the expectations that you have for anything that’s happening right now. For instance, I was once giving a talk. Similar to this and I heard something that sounded an awful lot like a gunshot. It wasn’t a gunshot. It was one of those light bulbs exploding but they sound really similar. But fortunately, I’m used to being on stages with loud light bulbs. My context is not somebody shooting at me dive for cover under the lectern. Very important when to time and observation to the world. So, we should understand the context people will bring to a situation, but we should recognize that we have some hazards. We have confirmation bubbles. evidence that fits our beliefs. We tend to accept. Evidence that doesn’t fit our beliefs, we tend to discard. We may not even Orient so that we can make a decision on it and we’re really great at rationalization. ‘Oh, I knew that was going to happen. So, I’m not surprised by it.’ And we often see this in one of my colleagues called historical paranoia. We do things because we’ve always done it that way and we’ve always been afraid. How many of you changed passwords at your businesses? Rotate your password every 90 to 120 days. You know why 90 to 120 days? Because when the NSA orange book was written that was how long it took to crack a password. Today your password is either instantaneously no longer useful or basically useful forever. But nonetheless we persist in making you rotate your password every 90 to 120 days. We’d be much better off investing all of that energy and getting rid of passwords within the enterprise. But we do it this way because we’ve always done it this way and the people whose job is to tell you to do it, don’t like asking and answering questions about why. Because they feel very overworked and that’s a challenge to their authority. So that goes into a lot of our models we don’t question why we do things. And then we hear stories and we just filter them away and believe them.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is a basic game taught in game theory classes in which you take two people. And you hypothesize that they have just robbed a bank and stolen a car. The police catch them know that they have robbed the bank but don’t have any evidence that will convict them but do have them in the stolen car. Grand Theft Auto is a problem but not as much as a problem or as great of a press headline as bank robbery. So, this is basically the premise of every police procedural ever. You split the two of them up and you offer them a choice. So, you say to them look your choices are that you may remain loyal to your partner or you can betray them and tell us the truth and turn state’s evidence. Now look if you are loyal to your partner and they’re loyal to you you’re going to jail for three years. That’s why it’s a minus three. This is a negative outcome. But if you remain loyal and they rat you out you’re going to jail for 10 years. That really sucks right. If you betray them and they’re loyal they don’t say anything we’ll let you off on a light sentence, you’ll only get one year. But we have to caution you if both of you betray each other you’re getting five years because now we have both of you confessing but we don’t actually need your confession for the other one. This has what’s known as a natural equilibrium because we offer the mirror of this to your partner. And what’s fascinating about this is you should betray your partner. If you read this and just do simple math. Whatever your partner does you’re better off. If you betray them.

And so, we do this study with grad students. Now, we don’t make grad students rob banks although one might argue that the US college system is something close to that. Instead we offer them things like free food because they’re always hungry. And so, we say look we could do this test with you and we want to see how often you remain loyal to each other versus how often you’ll betray each other. And what we discover is about 13% of the time both of you are loyal and about 40% of the time both of you will betray each other thus confirming our belief in humans that humans fundamentally are individualistic backstabbers. We’re going to screw over our partner at the first possible opportunity. That’s this mental model and this is replicable which is amazing for social science. Most social science studies are not really replicable every time you repeat it. You get different results. It turns out they’re really sensitive to amazing things. But this is like the study every economist does. You become a postdoc you grab a couple of grad students like hey I’m going to test on you.

Grad students are really crappy proxy for humans.

They’re what’s known as a WEIRD population; Western Educated Industrialized Rich Democracies is generally where they are raised. So, they have different beliefs in reality sometimes. And so, some researchers in Australia said you know this is a fascinating result but what if we tried this on actual prisoners. There’s a prison across the street. I bet we could offer them candy bars it’s sort of like free food. Now first of all, we should recognize that offering somebody candy bars or a free meal or $50 is nothing like the threat that they’re in when they’re robbing a bank and worrying about years in prison. So, we should worry about what this actually tells us. But when they did this test what they discovered. All of a sudden 30% of the time this group is loyal to one another. And 19% they’re betraying. It completely flips everything we might think about humans. Now there are lots of different hypotheses about why this is the case. Is it because they live with each other in tight proximity in a violent environment? And you want to be very careful about not having a reputation for screwing them over. Possibly. Whereas for grad students like they already know only one of them has a job and they don’t just know which one. So, you might as well start backstabbing early.

Is it because the prisoners recognize that this is not a two player game and the grad students are not wise enough to realize this? The UK has a game called Golden Balls which is fascinating which at the very end you have two contestants and they play a game like this. They’ve just built up this prize pot. They each have two balls in front of them that are steal and share. If you both pick share you split the prize. If one of you pick steal, they get the whole prize. If both of you pick steal, then the show gets the prize. And like this worked really great until somebody walked up one day and said I’ve just picked steal I’m not going to negotiate I’ll share with you I promise. But if you pick steal neither of us gets money. Two minutes of him just repeating this is a monologue like the show host is like what is going on here. And at the end of it he reveals he’s picked share and when they asked him, he said the most important thing was that the show not keep the money. He recognized that it was the two of them against the show. Turns out the other person who picked share is like ‘well if I pick steal, I get nothing, with share maybe I’ll get half of it.’

So, worked out for them. To recognize that people’s models might be a little different based on how they got there. They might have different beliefs. No decision is about risks. But everybody takes risks every day. If you think you don’t take risks recognize that you are spending an hour of your life listening to me talk. That’s a risk. I mean you came here to listen to a whole bunch of other people as well. You had to travel – that’s always a risk. So, you had these costs you spent, you expect some, you have some outcomes you’d like to get, and there’s some downsides that might happen. Now you’re going to leave behind hazards out of these decisions. Sometimes you don’t understand the costs and the returns are really complicated. Maybe they’re realities that somebody else pays. And so, our decision isn’t perfect with these hazards. And sometimes it’s because we don’t understand them anymore.

This is the Ford Pinto. How many people remember the Ford Pinto? The Ford Pinto has a design failure that if you’re not an automotive engineer is really easy to understand. To put weight on the back tires because it would skid, they put the gas tank right in front of the rear fender. Which meant if somebody’s rear ended you you’ve cracked your gas tank and you’re now leaking petrol all over your accident scene.

They didn’t blow up… Often.

But this is a simple hazard like I can explain that to you. And you can be like What were those engineers at Ford thinking? That is totally reasonable. Now, we think because of this like oh it should be easy to any risk calculations for those who have not seen this this is the security risk calculator often based on the insurance industry where we say things like ‘oh all we have to do is take a scenario, write down the loss – $5million, figure out the probability of it happening – 10% a year, calculate the ALE – that’s just annualized loss expectancy with our handy dandy risk calculator (which is always in excel), and we now know this risk cost us $500,000 dollars a year. Now I’ve totally just skipped over it. Doesn’t happen in nine years out of ten assuming my math was right. So, we’re not losing that money now want to buy some software solution that’s going to help save me money here at costs. Yeah or save me risk and cost me fifty thousand. The maintenance cost for it is fourteen thousand dollars a year. Note that that is 28% which is sort of the industry standard maintenance cost on everything. And it’s going to reduce my event rate by 10%. Now notice since I had an event rate of 10%, this means that instead of it happening one time every ten years it happens nine times every hundred years – which is very interesting math to try to do. But now we can calculate this as a $26,000 dollar a year cost, it’s going to reduce our risk by $50,000 a year which means we’ve just saved the company $24,000.

Which of you have ever seen a spreadsheet like this? They’re mostly BS. Because I can take this same spreadsheet and say well what about a business ending event that’s $5billion – that’s my scale $5billion – but it’s a 0.1% a year. Hey same annualized loss expectancy. It’s a one in ten thousand year event. I just gave out these really cool 20 years on the edge, because we’re a 20 year old company. So, hey I only got another 9,980 years to go before I know I’m going to hit this event. Same price of buying, same maintenance, same reduction, same benefit to the company. Does this make any sense as something you should buy? Probably not – especially not if you’re a startup. If you’re not yet profitable sustainably, you should not worry about risks that aren’t going to happen in ten thousand years. Maybe not even risks that are five years. But we think they should be. So instead often when we look at risks as a business, we build a qualitative risk matrix that looks something like this where you have high damage to low damage; likelihood goes from very to not very. And the hardest thing to decide here is to whether you should put priority two on the top or on the left. And what’s really here is this is not a nine box. It’s really a four box with a whole lot of uncertainty; like we believe in high and low and medium is just well I can’t really argue myself for sure that it’s high, somebody will tell me I’m wrong. So, we just sort of pick random things in there.

And this actually is a pretty useful way to think about risk management which is things that are obviously high damage and very likely, you should prioritize. You can kind of ignore everything else. Because risks now are really complicated, and they don’t make sense. Wired did an article a couple of years ago at the Jeep Grand Cherokee being taken over while the reporter was on the road at 70 miles an hour. Remember this one? Stunt hacking. The security community was all up in arms like oh my god horrible stunt. But it got press. It was very interesting. But what’s the problem? What did Jeep do wrong? On the level of what Ford did wrong like putting a gas tank in front of the Fender is an obvious dumb move, I don’t like saying that we’re done very often about what people do. But that’s in that category. But what did Jeep do wrong here? I mean you have a navigation system that needs to talk to the Internet because it’s pulling in serious data. But it also allows you to remotely unlock the car, so it’s got to talk back to jeeps computers. Cars don’t have a lot of extra space in them. So, there’s only one BUS running within the vehicle for transmission in the canvas and it can be used to send messages.

And now it turns out that vehicles aren’t cars anymore. And this was a real eye opener for me. What a vehicle really is is a network of computers that are self-mobile because when you turn the wheel on a modern car what it’s doing is it’s sending a computer message across a network to a wheel that says ‘I would like you to do the following’ and turn the wheel. We don’t have rack and pinion steering anymore. When you push the brake pedal, we used to think of that. You push the brake pedal the drums expand. Nope it just sends a message that says hey I’ve been pushed this far, do the following on every tire. That’s kind of scary when you think about all of those messages going on the same communication system that Jeep can talk to from its computers, wherever those happen to be, and that’s what the stunt hack was – broke into those computers sent a message to that car that instead of unlocked the doors happened to be accelerate the car/hit the brakes. Scary things that can happen but there’s not an obvious single thing that Jeep did wrong. There’s a whole sequence. Complex systems are hard to understand.

People are different

Also, important to understand that the risks to people are different. So this one’s audience participation. I’m going to ask you all to raise your hand in a moment and then put your hand down when your answer becomes ‘No’. In spirit of the earlier one I’m the game master. I have a 20 sided die. You get one opportunity to play this game, this is not iterated, and you get to bet some amount. If I roll your number, you get 20 times that amount plus your original bet – because I’m bad at math. If it doesn’t come up, I get to keep your money. Now. What this means is you’re expected a 5% payout. This is great. Like a house in Vegas that did this would be out of business almost instantaneously. So, put up your hands.

Would you bet and play this game at $1? Yes.

- $10?

- $100?

- $1,000?

- $10,000?

- £100,000?

- $1,000,000?

Oh no. So, the best part is, Mark is not the first person to leave their hand up at a million dollars. The first person who did worked for the army and they did tank acquisitions. And he said, ‘Dude I will totally bet a million dollars on another 20 million because I probably lose that in waste anyway, but 20 million I could really use.’ But what’s important here is that from a known simplistic model of the human. This is the same game. Either your hand is up, or it is not up and yet we all put our hands down at different times. Why? Because we have different things to lose. You know I play this game probably for a hundred bucks. Because 100 bucks is a nice meal. I can skip a nice meal it’s not going to hurt me. There are people for whom 100 bucks is significant value. They’re not going to play a game like this. With one hundred dollars. Because what you really value something is what you give up. What’s your cost is a personal cost. It’s about what you’re giving up. So, you should worry about people who are disconnected from their costs. A product manager doesn’t bear a cost for a bad decision. That is a concern because they might be willing to take bigger and greater risks.

Now you can’t get people to take no risk because there’s an amount of risk that people are willing to take. It’s known as the Peltzman effect. You’d move it along. You have some amount of risk when you learn about or risk change all of a sudden, the world is scarier. What do you do? You act. You’re going to drive back down your risk to where you thought it was before. And this is all about perception. It’s not that humans run around calculating risk, but if we just got a note that said ‘hey look five people got mugged in the parking lot across the street’ all of us who were in the parking lot are going to be like ‘hey when I’m going to buy cars you want to walk with me, you know so we don’t get mugged?’ We’ll just take some action.

Now the interesting thing is this works in reverse. If I take risk away from you, you behave more dangerously. It’s called this the Peltzman effect because Sam Peltzman was an economist at the University of Chicago, who when the US was debating a national seatbelt law back in the ‘80s he said look if we make everybody wear seat belts they will drive more recklessly and they will kill people. Killer seatbelts was literally the headline in The New York Times. Which is the I guess it’s credible now as it was then. And Sam Peltzman said look if you wanted people to drive safely and not be at risk of killing other people, you only need one safety device in cars.

The histrionics aside Sam Peltzman is probably right. If you look over the last 40 years at the traffic safety information, that the U.S. conveniently collects, you’ll notice that drivers die at a much reduced rate than they used to. And it’s been consistently going down for quite some time. Passengers going down but not nearly as fast. Pedestrians appears to be about constant which is very interesting. And motorcyclists are dying at a higher rate. Because motorcycles are the people who take the biggest risks interacting with cars.

And we now think nothing of driving 90 miles an hour on a highway. 40 years ago, nobody was doing that. Well not nobody but. Only people in movies. Or who thought they were in movies. So that’s how people decide. Let’s think about attention; attention is fascinating. This is about what you notice. It’s about what’s near you, what’s new, what’s urgent, but it also has hazards. We don’t notice everything in the world but the things we noticed are often primed to get our attention. Facebook is perfect at gaming the attention economy. Distributed social networks that bring information to us quickly with visuals are basically designed to make you observe them. And that’s what the ad market is all about. And this can be a problem because there are any. Around 11 million bits per second of information that are hitting your body for most normal people. Do you want your cognitive capacity is to consciously process those? 40.

Four Zero

We have to weed out basically every piece of information. As an example for you, how many of you- before I said the sentence – were aware of what the seat feels like under your rear end? Basically, none of you unless you have sensory processing disorder. I’m the guy who always raises his hand because I’m like ‘No, no, no. I feel all fabric on my skin all the time. It sucks.’ That’s basically with sensory processing disorder is you can’t stop ignoring one or more of your senses. So, we have to weed all of these out and how we do it is very interesting.

So for those of you who have not seen the invisible gorilla sketch I’m going to spoil it for you here because I don’t like running the video because most of you have already seen it in this one you tell people ‘Look there’s these people who in white shirts we’re going to be passing the basketball around count the number of times they pass the basketball.’ And there’s people in black shirts also passing the basketball and people will be counting and in the middle of this video this person in a gorilla suit walks out, sits in the middle thumps and then walks off and half of the audience will not see it. Selective attention. At any given point there’s something you’re focused on. And you have non-unconscious systems that are basically weeding out anything that is not relevant. But you wouldn’t believe this. You say ‘no, no, of course I saw the gorilla’. Now if you want to experience this if you go to the invisible gorilla you can see a whole bunch of videos they’ve done that don’t involve the gorilla. And it’s a lot of fun. This is basically how all stage magic works. If you ever if you like watching a stage magician, the fascinating thing is the moment you think they’re doing the trick. They’ve already done the trick. They’re just forcing your attention over to somewhere else. So that you think you’ve been fooled.

Now what’s really happening here is the end result of hundreds of millions of years of evolution. These are all critters that have split off from us at some point on the evolutionary tree. I love looking at the Hydra. The jellyfish as the first example. The jellyfish splits off from us I think five hundred million years ago and what’s fascinating is if you touch a jellyfish or a jellyfish it’s covered in sensors it knows it’s been touched. Knows is an interesting thing – it has a brain, but it doesn’t know how to distinguish between one sensor and another. So we’d be like if I sat and stood here and asked somebody to shout in the back half of the room something and tried to figure out who it was. I happen to be deaf in my left ear. So, I have no sense of sound location if I’m not looking at you. But that’s okay for a jellyfish. They don’t have to know where they were touched, because it doesn’t matter. They only have one thing available to them. They can spasm their whole body – I like to call it blorping -which will move them in some direction. Now if they’ve been touched, they’re about to die. Okay fine I try to move. Either I die a little faster or I get away from it. That’s the only choice they have to make: move or don’t move. But you’re going to die anyway. It doesn’t matter which whether you’re going to be eaten on the right side first or the left side first. So, they don’t really have any hardwired systems to change their attention.

Fast forward to the insects. Insects are amazing because they start to develop hardwired sensors inside their sensory system. We talk about the ant is having these multifaceted eyes and how they can see so much of the world. But what’s fascinating is as soon as they actually focus on a thing only one facet really works. That’s what’s transmitting into their neural system; it’s whatever they’re looking right at. And even though they have facets that might be seeing the rest of the world it’s gone from their attention. They can’t look at it; they’re literally have a single spotlight to look at the world. Which is sort of similar to how our eyes work. We just are a little more complicated. If you’re looking straight ahead the things in front of you, you have really crisp clear vision. But off to the side, in your periphery, you don’t have clear vision you can just see movement. Why? Well because what’s important is what you’re looking at. But from the sides we like the extra sensor of like is a predator about to jump on me? If so, I should look over and dodge it.

Reptiles or even cooler, the large predator reptiles predict the future. They developed the wolf pre cortex. And what happens in the Wolf is they predict a model of what they’re going to see that is integrated with their own motion. So as they turn their head what the wolf is doing is predicting the pixels that are going to come from its line of sight, and then it compares them to what is coming in from the world and the deviation says that’s prey. Something is moving. That’s why one of the recommendations is if you’re near an alligator or a crocodile is not yet charging you; stand still, it might wander away because now you look like a tree. Because you don’t move not because you happen to be wearing the right colour clothing.

Now fast forward to humans and I’m skipping over a whole bunch of different thing birds are fascinating here as well. And humans not only have all of these features sort of baked in. We also start to develop really cool models of agency for the world. Like birds understand that other birds are also agents and that’s why like crows will hide food. See another bird. Wait for the bird to leave and then move its food. Humans see something happen and say ‘oh the grass is moving that might be a Jaguar’ or ‘the grass is moving in a weird way and there wasn’t a jaguar that might have been God’. We invent gods to explain in the world. Because we need to have a model of what’s going on so that when we observe a thing, we can fit it into our observation. So why do we have seasons? Oh, because perception is in the underworld and bad things are happening because Demeter is crying. We tell ourselves these stories. Now it’s important to understand that that lets us take our attention and say yep I have a reason for it. I can observe it. I can orient and I can move on. And that’s part of what makes the human fascinating from an attention perspective.

The things that we’re going to really orient ourselves around from an attention model are the things close to us. We care about our tribe. If I live in the desert and all of a sudden, a small child in the family gets stabbed with a scorpion. I should worry. Scorpions are a problem in the desert. This is new. None of us have been stabbed before. It has happened to somebody near me and it is urgent, I have to deal with it. If I hear about a story of some other tribe whose children got mauled by polar bears: Not near me, not my family, not urgent, don’t have to worry about it. That is basically a high level heuristic for processing new and novel things. How much is it likely to affect me and mine. So, you are really familiar with Dunbar’s number the hundred and fifty people that you consider part of your tribe. It’s what a society can sort of hold in itself. This is where it comes into play for priorities a for prioritizing news and information.

Now of course risk comes with action. We have to decide what we’re going to do and then do it. Now we’re really great at things we’ve done before. If we’ve practiced them their actions that are low risk to us. But the challenge we sometimes have is we’ll take those actions and we will repurpose them in places that they are not appropriate. Or we think we’re really good at something. So of course, we’ll just jump in and solve a problem. I am really great at putting bandaids on my kids. This should not extrapolate too I’m good at giving first aid. No. Bandaids on children, that’s the limit of where I am but I have seen parents who like some child is injured and they’re like oh my goodness let me come in and solve the problem. And I’m like which parent is a doctor or nurse? You, you come solve the problem because that’s what I’m really good at is assigning resources to problems. I should recognize that that that’s a skill I should always use there. And what’s fascinating here is how these all sometimes get put together.

Right or Left?

So again. Audience participation I’m going to put words on the screen. And you’re going to tell me if the word appeared on the left side of the screen or on the right side of the screen. So first one’s going to be really simple.

Excellent. You’ll all be reporting to Paris Island for induction into the U.S. Marine Corps a little later today.

I’m going to mix it up a little bit.

What happened there? Come on you guys were so good on the first slide. So what just happened there was machine learning. So you now all know machine learning is it’s a buzzword. Machine learning is patterned after what humans do naturally. Daniel Kahneman records this is what he calls system 1 and System 2. If you thought using Grad students was bad, the naming that people often use. System One is the system that does not require conscious cognition to run through your OODA loop. It can do stuff and act without you ever making the choice to do so. And it learns what happened was on that first slide we trained your machine learning system and you know what’s really hard for your unconscious brain to do: Left/right discrimination, but reading totally easy so it said oh I’m just reading words off the board. The first time a word conflicts about half of use say read the word and half of you’re like Oh man I’m going to say the wrong thing so you pause and you say it and then going forward it is slower your voices actually become louder and more focused. Because you are now consciously engaged in the system but you’re spending calories. This is why we don’t engage system 2 all the time. System 2 is wicked expensive. Humans have two evolutionary advantages that put us on the top of the planet. One is our asses. We are designed to be persistence runners. We can hunt anything on the planet. If it doesn’t eat us, we can chase it down; at least our ancestors could. Most of us not so good at it. But the second evolutionary advantage is that we are optimized to not think. We developed brains and then we optimized ourselves to use them as little as possible and only when it mattered. And what happened here is your brain optimized itself out of the equation and said I’m just going to sit here I don’t want to burn any calories because dinner is coming up in like 20 minutes and I’m starving.

But when we put all of that together some really fascinating things start to emerge. Humans are situationally awesome at risk management. There are situations in which we are really good. If we have a coherent model of the world with which to orient ourselves. If we bear the costs of our choices ourselves and we understand them and we understand our returns. If we are paying attention to the world and we have the right capabilities to act. That’s our situation.

Now this doesn’t mean that every human is personally good at risk management. In fact part of what makes us the dominant species on the planet is that a bunch of us are really bad at risk management and some are really amazingly good but we don’t really know how to tell the difference. Evolution just sort of gives us a hand and we have random scattering and the ones we’re really good at risk management survive and the ones who don’t, unfortunately don’t die off anymore. So we may be getting less good at risk management going forward. This is not actually a request to bring back like the Dark Ages or the Hunger Games.

But what’s important to recognize is that our OODA loops run in this subconscious fashion and they’re what they’re what filter out all of those pieces of information from the world. That’s how we get down to 40. Some of it is physical happening inside our body and our sensory apparatus some of it is happening inside of our brain that we’re not seeing. And if we want to make better risk choices it is sometimes up manipulating these manipulating the inputs and our beliefs and our models of the world. So that this system does better for us. So that the choices that we are faced with making are actually choices where we have an opportunity to be wise. And to make good choices. So we should understand what these hazards are and think about how we might change ourselves for the better. In that security conversation the way I solved that problem was really easy. When somebody asked me if a product was safe, I just said I don’t know you tell me. You know more about your products than I do. I can’t tell you if they’re safe. I can teach you to think about safety. But even if you’re only 10% as good as I am at thinking about the safety model of a system and you write down only 10% of the risks that I would find. You will still make a better choice now than ignoring the 100% I write down. Therefore, I should make you think about the risks rather than doing it myself.

Adversaries

And so how do we do this. We model how adversaries use the OODA loop. What’s fascinating is Boyd solved this sort of for us. He said,

‘An adversary is doing the same thing to you, and so I posit we can think of ourselves as our own adversary.’

So what does an adversary do? They attack our decisioning process. If I want to mess with you I want to distract you or blind you from evidence. I want to make it so you can’t see the right things or you see things that aren’t important. Adversaries do this all the time. They’ll either inject bogus information or they’ll do stealth to hide themselves.

One of my favourite stories here was about the Zeus botnet. For those who never heard of it, it just stole an awful lot of money from a lot of banks. What it would do is it would compromise somebodies computer and when they would logged into a bank would watch for a wire transfer. It would look to see how much money was in the bank account, and if enough was there it would change the wire transfer. You would type in ‘send a thousand dollars to my brother’s account because we’ve got to make payroll’ and it would change the submission that went back to your bank and it would say ‘wire ten thousand dollars to this bank in Hong Kong’. And then what they would do is they’d send this message back to themselves to the command and control to say hey we’ve just stolen a bunch of money from like 50 different accounts. And now they would launch a denial of service attack against the bank’s Website. Why? Well, all the banks incident responders are now focused on ‘Oh my God our bank site is down. Let’s bring it back up!’ and you the person who just transferred money can’t see that the money went to the wrong place. They have both distracted the responder who would help you and they’ve provided themselves stealth. That means you don’t get observed.

From an orientation perspective an attacker wants to induce complacency or confusion. And the tool that they use here is misdirection and coming back to the stage magician what does a good stage magician do? She provides you with misdirection often by injecting or concealing certain activities that are happening.

For decision in an adversary really just wants you to do one of two things: make the wrong choice (mistake) or get stuck in paralysis. Oh my God I don’t know enough or this isn’t really a big deal. Now again they’re going to do that having used misdirection they want to be surprising to you, give you something that you’re unprepared to deal with, or that misleads you that makes you think you have a different problem.

And, of course, how you negate action is with ineptitude. My favourite story on this one was I was working with a retailer and they had an account credential stuffing bot that was attacking them and what account credential stuffing is all of you have usernames and passwords that have been compromised. Period end of story. There they’re out there. You know somebody’s got breached that you had an account with. Now if you reuse that username and password at some other Website well what the adversaries do is they just have this database and they’ll go over to somebodies website and say ‘hey has ML*********@bu****************.org have an account here with the password ‘MyConferenceRocks’? No? Okay great I’ll try somewhere else.’ They go to the next place. And this retailer was under attack and they had this system that would detected a bot network was doing this and they would identify the bot and they would block each individual bot as it came along, and it took them forty five minutes from when the bot first showed up until they could block it.

Now if the bot move too fast they could block it basically instantly but if it was just trying like one username and password a minute it got forty five tries and then they could kill it and one day they had a problem in their system and it took 90 minutes. And when they went back and looked at their logs they discovered. The bots only attack them for forty five minutes. Because the adversary had measured and monitored their response and had made them inept. The adversary went away after forty five minutes. Their security system was completely valueless at that point.

How the adversary does that is by manoeuvring faster than we do. They predict what we will do. And they’re going to respond to it before we even do it. Now this can sound very scary and this is sort of the downside, but the upside is we can use some of these same techniques on ourselves and we can think carefully about how we make choices to improve ourselves as well. So, the ways that we can do this is from an observation perspective, we can reduce the noise. We can look at the inputs that we are taking look at the ones that don’t matter that we ignore anyway and stop paying attention to them because they do consumer cognitive capacity. They distract us from the things that matter. So, if you’re looking at a thing and you’re not going to make a choice based on the thing, stopped looking at the thing.

We can also instrument the things we do really want to know about. You know for me I actually have a really simple one here because I have a staff meeting and we do a lot of hiring. And one of those frustrating things is when hiring isn’t moving very well but you’re meeting with somebody every week and you’d like at what point do I care? So I instrument it. I say at what point do I care? Don’t tell me until you haven’t made progress on that day. And then let’s talk because that’s a problem. Reduce the noise of everyday being told every week being told well we have some candidates in. Well in a month if you haven’t made an offer or had a candidate go to second round I want to understand why and what’s wrong with our process.

For better orientation you really need to understand the hazards of your business. And hazard is one of those words that’s often really loaded. And in this case, I just mean the dangers that surround you. And sometimes those hazards are self-induced. You wrote software it might have bugs. You have an operations team it might not scale. Sometimes they’re not self-induced. You have competitors they might out-execute you. You have regulators they might put you out of business. Like when you’re trying to sell baseball cards at lunch with people’s lunch money. That’s a hazard, helps to make it a business decision. They exit $400 to the better. You know they weren’t over leveraged at that point. So have a good analysis of your model. Understand why you’re making the choices that you are making and why you’re taking certain inputs

From a decisioning – this is one of my favourite buzzwords – this is me using big words just because I think they make me feel smart Bayesian retrospection. This just means that when you make a decision, record what you think the outcome is and why you believe that. Write down your priors. And then after the decision has effect go back and look at it. Then did what I expect happen happen? If not is it possible that I was wrong in my beliefs about the world? That’s it. Look sometimes you’re rolling the dice. If I’m rolling D6. I should not be surprised if I sometimes roll a one. If I roll a seven. I should be really surprised! And say oh what happened here. I thought I was rolling a six sided die and my output was a seven. Something’s wrong with my belief about the world so I’m not making good decisions. So, write them down.

It’s having better planning. You make better decisions when they’re not in the heat of the moment. That’s the HIPPO problem right. Why are HIPPOS a problem? Which you discussed earlier is not that it’s just the highest paid professional it’s that they are walking in and making the decision cold. It’s not a planned decision. It’s not thought through. And so, as the system becomes more complicated you are more likely to ignore the complex parts of the risk.

And from an action perspective understand the consequences of the choices that you make. All an impact assessment is; if you’re going to launch a product what’s the worst possible thing that could happen? Sometimes the answer is nothing, we just wasted the money on whatever we built the product failed. No big deal. Sometimes it’s you launch your product and you’re sitting in front of Congress having to explain why you just launched this product. And you might have investors coming looking for your hide because your money wandered away. And it is about training. It’s about practicing the things that you want to do so that when it’s time to do them you are prepared to do them. That’s it. This is not rocket science. I mean its brain science but that’s almost easier in many ways, because the best part is every human is different. You could experiment on yourself on the people around you and your lessons are what matter for you.

So, for one person it’s all let me just practice writing down ‘hey here’s what I think the outcome of this choice will be. Let me come back and look at it after 30 days. It wasn’t that. Let me try again.’ For others it will be different things that will work best for them. So, thank you, I appreciate your time, and I think I have a couple minutes for questions.

[Applause]

Q&A

Audience Member: Thank you for a fantastic talk. One thing that surprised me early in your talk was your seeming dismissal of exotic risk, like the five billion dollar example. Cause even though it is relatively rare it was death. And there’s a difference between colds and cancer. So, I was wondering whether you could talk a little bit about how to evaluate risk that is exotic and rare but has overwhelming consequences.

Andy Ellis: So, for four exotic and rare risk the way you evaluate it is not quantitatively. You should recognize that that is exotic rare risk and you’re going to make a value judgment. Do you care? Well here’s the reality for many of you who are in startups and small businesses that are not yet sustainably profitable. Your business is going to go under at some point. Actually, it’s not because you’re here and you will learn amazing things and you’re mitigating risk. Make sure to help Mark out there. But for most startups that’s the reality from the moment that someone says I’ve got an idea for a company and they figure out how their use is spending their first dollar. They’re doomed all right. And there are zombies. This risk model that I’m giving you for sort of how humans think about risk works for humans. Why. Because humans think they’re immortal. I have lost 17 pounds in the last five weeks. Why? Because I went to my doctor I’d put on a bunch of weight because I was on steroids for a hearing problem, and I went to my doctor. He did all the bloodwork. He says you have two choices: He says you can either take off a bunch of that weight or you can kiss goodbye your chance of seeing either of your children married. I think I’m immortal. That’s terrifying. I’m losing weight. Really simple.

But imagine if I’m not a human, I’m a zombie and I know that if I don’t need brains every day I die. That risk, totally not a problem because I need to eat brains. And so that’s why I’d like every zombie movie like the zombies are reckless and dangerous and they take stupid risks and they break limbs because if they don’t eat brains they die. Startups are like that. You know the date of your death. If you don’t know the date that your company is going out of business, you’re doing it wrong. You should have that date and any risk after that date you probably shouldn’t preference. And those exotic risks like do I worry about my corporate headquarters being struck by a meteor? No, because realistically there’s nothing I can do anyway. But my headquarters is in downtown Cambridge. (The cooler one not the older one). I’ll give him credit, you had it first!

Mark Littlewood: proper Cambridge we call it.

Andy Ellis: And that’s a choice that we make but it means if somebody wanted to blow up my building, they’re going to blow up my building. I just accept that. I write it down. In fact, that’s the first example I use on every one of my new board members. It’s fantastic. Why? Because it lets them understand that when I now talk about the risks, the exotic risks that were not mitigated, I have a framework for saying look we’re going to pay attention to that risk. Maybe someday there’s a different risk that’s on that register that we’ll take care of and we’ll do something with it. But these are just going to be value judgments that we’re going to trust the humans that are making them, but we’ll make them with transparency. We’re not going to hide it and we’re not going to put it in a spreadsheet so that we can pretend it’s not real. Those are real risks. But they’re not risk that I’ve got a mathematical way to address them.

Mark Littlewood: How did you know my password by the way?

Andy Ellis: Well you know about that data dump…

Audience Member: So, I thought this was fascinating the decisions aspect of risk and the way the loop goes through etc. But what about luck?

Andy Ellis: What about luck? Well he just retired from the NFL – sorry Colts fans.

Audience Member: specifically looking at bias and how that goes.

Andy Ellis: Oh, so huh. Well we could do another hour on bias and luck. Let me take bias first and then luck. So first of all, the world is biased. Let’s just start from right there. Mark and I do not have the same evolutionary advantages. Genetically we got different things we had different, even before we talk about how we were raised. I am envious of his ability to look at somebody and know their name. You’ll notice he’s the only name I’ve been using today because I’ve met like 20 or 30 of you. Sorry your names are gone even those of you I’m sitting next to I think there’s a Gareth over there but I’m not positive, but which one I am not sure.

We have different skills. The world is biased against us. I have this wonderful advantage; I could take this microphone off and all of you could hear me. That is a gift that I just have. Now, then there’s bias that since I know humans naturally hear me. Then of course every manufacturer of technology then filters for my voice. Sorry. Those of you who have higher pitched softer voices, mine is the one that they want to amplify more. I don’t know why. I don’t need it. But that’s the reality of the world. So, bias comes in and a lot of places. Often, we make it worse. Sometimes we make it different.

And then luck stacks on top of that. And luck helps us sometimes look at things that happened and guess wrong. So, we say Oh look I thought that rolling this die would give me a great outcome, and it did my 20 sided die came of twenty five times in a row. I’m a great decision maker. No. I needed a 20 every time I saw I had five great outcomes. And this is where we run into biases around you know survivorship and you know winners in the halo effect because we look at this people who succeeded and say oh what did they do right. It reminds me of. I think that was at the RAF who did the Air Force during World War 2 that was the planes that were coming back and they said like where are all the holes in the plane that’s where we need to put more armour until some genius person said wait. Everywhere we don’t see holes coming back means the plane got shot down by getting hit there. Let’s armour the spots there instead. So, some luck for some of those planes, changes our bias, changes our decision making. So, the important part is to be introspective. The trick that I have tried to use for me that works well for me is to ask a question all the time which is: how could I be wrong? And how could this other person be right? Especially if I’m not inclined to agree with them. You tell me a thing that I my first reaction is that can’t possibly be true. Then the next question I have to ask is ‘how could it possibly be true’. What is right about the world that you see that is wrong from what I’m seeing so that I can improve that. And that’s often how you might filter out luck. Also look over a long trend. Luck is very rarely going to be continuously good. You’re not going to roll five 20s and then keep rolling five 20s if you do check the dice maybe they’re loaded.

Audience Member: So, thanks for the talk. Amazing. I think one of the things I struggle with is how some background insecurity when you combine that with the availability bias. The point is you talk about hey I’m talking about 10 risks. But the fact that you talked about those 10 risks is no that the liberal announced. Yes. For me I can look at them and say hey it’s a loss. I told you about it because somehow, I’m supposed to tell you about it. I’m a security person. But then now know that you talked about it. You got to do something about it right. And then how do you deal with that availability bias?

Andy Ellis: Yes. So that is actually one of the I think the worst sins of my profession is that we hide risk from people. I make no risk decisions other than in what I tell you about. That’s the only meaningful choice I ever get to make is in what I’m going to tell my business partner about because they’re the one who decides what to do, I just advise them. And so, for instance one of the things we do is we have what we call the severe vulnerabilities which are the nine biggest risks we’re currently engaged in doing something about. And now we call them the severe vulnerabilities because that’s a great phrase- everybody pays attention. And but the only reason they’re on that list is because it means I need to executive vice presidents to talk to one another to solve the problem. Like that’s basically the root of every severe risk. Two executive vice presidents. Their organizations are not talking to each other. And I need both of them engaged. Now I only have capacity for nine to move forward at any one time. Now nine is not because we went and measured and figured it out it’s because every time, I’d seen somebody create a top 10 list because 10 is the perfect arbitrary number. Everybody recognizes it’s arbitrary and that’s kept adding to it. Oh, if you could take 10 you could do eleven nine, you’ve got to believe I’ve got science behind nine. Trust me.

So whenever we had an opening like we have a candidate like oh look we’re about to close once let’s start opening one up and now look I’m really good about saying if Mark’s working on three I shouldn’t bring him another one. He’s got some limited capacity. He’s got a business to run. I should bring it to someone else. I walk up and I say great, we need to open up a new one. And I’ve got a whole register of them. Here’s the 13 that I started looking at. Here’s the eight that maybe we could make some progress on. Here’s the four that I think would be good for us to pick from. Now you pick one. First of all, it now tells you that that one is not really the most critical one. It’s not that I whittled it down to one because what I’m really prioritizing is what can we make good progress on. It’s much more important for me than somebody solve a minor or moderate problem, than they work on a hard problem and don’t solve it. Because one the world gets better when people don’t want to listen to me anymore you spent three years working on a problem it didn’t solve it. Don’t listen to the person who brought you that problem is the very easy reaction to half right. So, I always want to be transparent and expose the risks to you. Also, it makes that one more meaningful to you. You’re like you chose it. It’s the one that you thought was most important out of the four. So, you can’t say ‘Andy why did you tell me to do this one’. I totally didn’t tell you to do it. I had three others that I thought were just as cool. But you knew more about your business and thought this one was more addressable. How were we both wrong in that I thought it was doable? And you thought it was the most doable and we were both wrong? Let’s figure that out for next time. But now it’s a partnership. And so that’s how I look at everything in security. Security professionals are nothing more than advisors to a business. We happen to have deep expertise in very specific ways of making the world suck more. That’s it. I can brake systems if you give me any system/any process. My talent is I can look at it and find all the places that I can make it suck. I can also often find the places I can make it better. That’s the skill I want to use. But sometimes I don’t know the costs of those choices.

And so, all I can do is advise you because you’re the one who has to own the new process after it’s done.

Sketchnote

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.