Influencer Marketing is big business but in a very short amount of time it has become so rife with fraud you cannot trust what you read on social media.

On Saturday, the New York Times published a detailed expose of the activities of a Social Media Influencer company called Devumi who sell fake and fraudulent followers and engagement to people desperate for validation and influence. Influencers peddling their shtick to the world are fraudulently misrepresenting their ‘influence’ for financial gain. They’re everywhere these days and they are making money as a result of their fraudulent behavior in all sorts of ways.

How do you spot the frauds and fakes?

Using fake accounts to misrepresent ‘influence’ is fraudulent as the ‘influencer’ is using deception to secure a benefit, whether that be financial, reputational, social etc. This might be by being paid to tweet a promotion for a product or, for example, to create a false impression of the value of someone’s work in order to secure more, better paid, speaking engagements.

It so happened that when I read the story, I recognized the name of one of the social media influencers that was mentioned as we had recently had some interaction on LinkedIn where I suspected the guy was just one of those regular, desperate, self-promoters that peddle their content and views.

I took a look at this person’s Twitter account, in the light of his comments to the New York Times.

“No one will take you seriously if you don’t have a noteworthy presence,” said Jason Schenker, an economist who specializes in economic forecasting and has purchased at least 260,000 followers.”

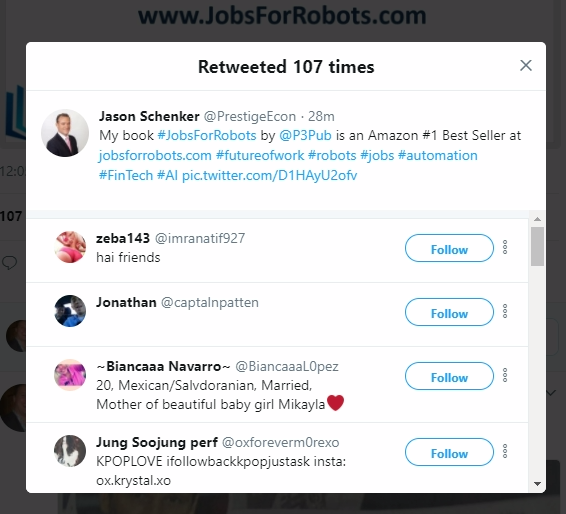

So Jason bought fake followers to get taken seriously. Perhaps ironically, Jason Schenker (320,000 Twitter followers, though remember he has purchased at least 260,000), has written a book, ‘Jobs for Robots’.

He certainly keeps those robots busy…

Here are eight strong signals that someone is faking influence.

1 Lots of followers for a relentlessly self-promotional account

Pretty obvious this one. When someone tweets constantly about their talks, books, articles, awards and share very little content that could objectively be viewed as interesting, your mind isn’t playing tricks on you. Trust your gut instinct. Number of followers is simply not a good measure of influence.

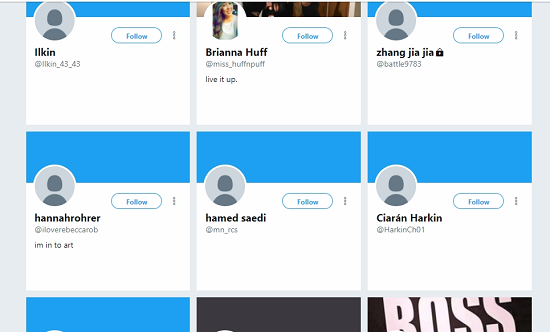

2 Low quality followers

Eggs, avatars, strange accounts. All good signs that an account has fake followers.

3 Lots of likes and retweets for every post

In Jason’s case, all of his words of wisdom are rapidly retweeted by, typically by around 100 or so people within an hour of the tweet being sent. This doesn’t necessarily mean someone is faking their influence though it doesn’t feel quite right that every tweet, regardless of content, is enthusiastically retweeted by a reasonably predictable amount of people in short order.

4 Check the accounts that do the Retweets

This is usually a complete giveaway. There seem to be more ‘real people’ (ie not eggs) retweeting the content, but is it likely that the accounts retweeting the original tweet would be interested in the content?

When people use Twitter to create fraudulent influence, there seem to be three common attributes that the accounts they use share:

5 High following counts (usually c 5,000) and low follower counts (c 100 or so).

6 A highly eclectic set of ‘interests’.

‘Erin’ for example has retweeted tweets about the Grammys, Bitcoin, restaurant reviews, undersea exploration, a few motivational quotes, the list goes on. She never tweets, only retweets.

7 Something not quite right about the accounts.

Even the accounts that aren’t obvious fakes, often look similar to real accounts. For example one of the accounts that retweets Jason could look at first glance to be a legitimate account.

It even links to a real firm who had no inkling of their fake account. Why should they? Even if they googled themselves, they would be unlikely to find the account – note the spelling of ‘Capital’ – ‘CapLtal’.

(The real Hold Brothers Capital has reported the account to Twitter. As yet, the account remains live.

8 Never goes to bed.

Erin is a machine. She never sleeps. She tweets all day, every day.

While none of these things in themselves necessarily mean that someone is attempting to build influence fraudulently, (in theory, someone could be followed by an army of bots that retweet everything you did without your permission for example), taken together, they offer very strong signals that someone is not as influential as they would like you to believe.

Sadly, it would be completely trivial for Twitter to put in place a few checks that could solve so many of these issues of fake influence but it seems that if they did, they may find far more of their accounts are fake than they would ever admit and that would be bad for shareholders.

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.