Teresa Torres is a Product Coach at ProductTalk.org advocating strong critical thinking practices to ensure there is a strong connection between what teams are learning in their research with the product outcomes that they are making.

If you are like most leaders, you got to where you are because you are good at making decisions. You can quickly go from strategy to execution and you know exactly what should be done next. But if we make all the output decisions (e.g. what to build, what programs to roll out, how a process should work), our company’s solutions are only as good as we are. To avoid this trap, instead of telling our teams what to do, we need to tell them what outcomes we expect them to drive. This talk is from BoS 2019.

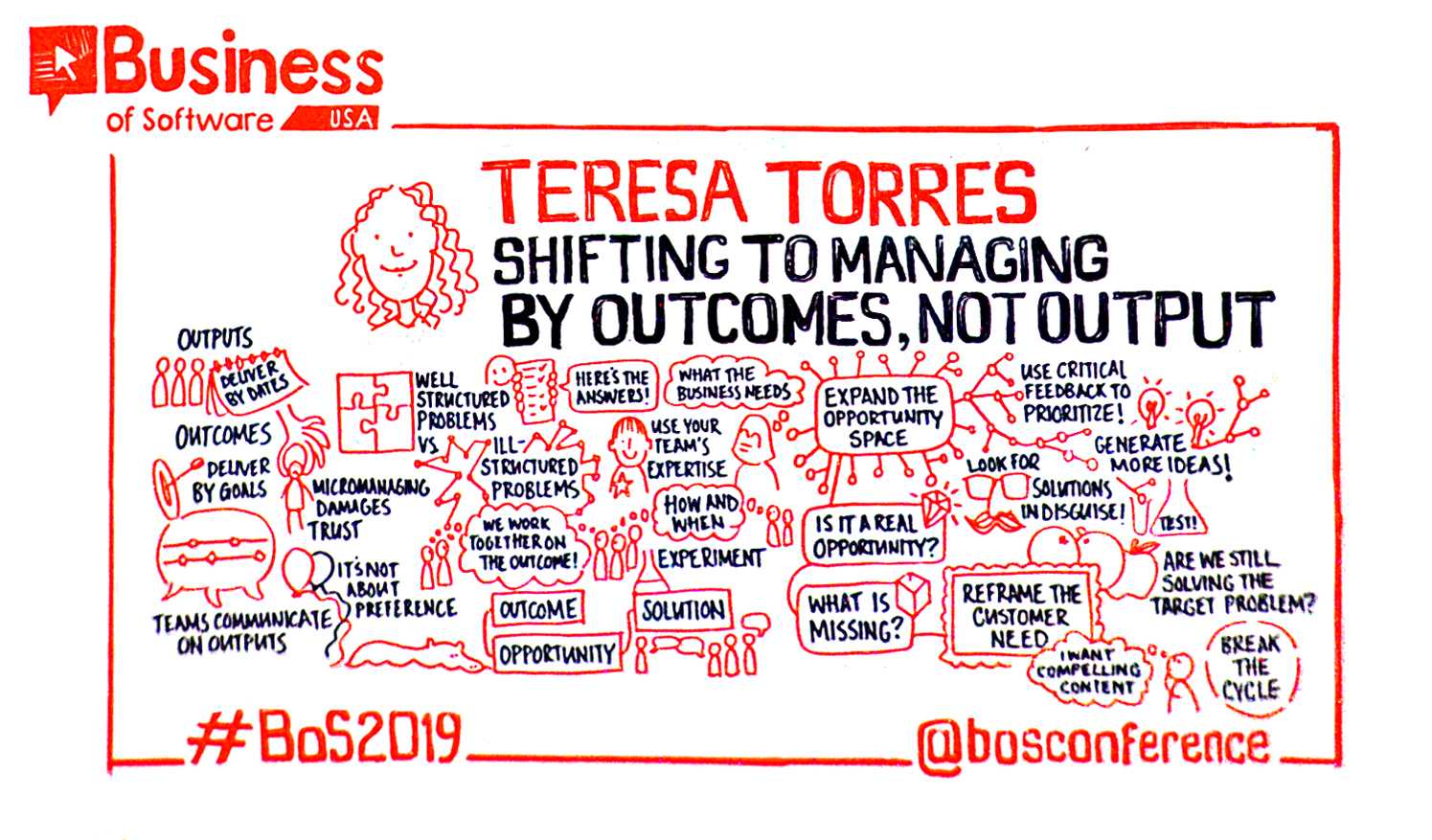

Find Teresa’s talk video, slides, transcript, sketchnote, and more from Teresa below.

Find out more about BoS

Get details about our next conference, subscribe to our newsletter, and watch more of the great BoS Talks you hear so much about.

Video

Sketchnote

Slides

Transcript

Good morning everybody. I’m losing my voice hopefully and I have to stop and drink water twenty five times we’ll see how it goes.

So today I want to talk about managing by our outputs versus outcomes. I realize from talking to people yesterday that we have a lot of sort of diversity in the room in terms of how familiar people are with this concept. So, it would really help if as we kind of go through this I can get some feedback from folks about what you’ve heard what you’ve done. So, I’m going to start with, yesterday we learned from Whitney about OKRs – that is one way of trying to manage by outcomes. This is an old idea I think Peter Drucker talked about it in the ‘60s, Andy Grove has talked about it in his book recently more popularized by Google. I think Harvard Business Review wrote about it in 2012 – which means that now the idea is a hundred years old – but here’s what I see: even though we know that we should be moving towards managing by outcomes (and we’ll get into what I mean by managing by outputs versus managing by outcomes) even when we have drank the Kool-Aid and we want to do this, it’s actually really hard. And it’s really hard for us as leaders because our role in our organization changes quite a bit. So what I want to do is talk a little bit today about what this even looks like, and why we struggle with it, and then hopefully give you some tips for how to think about how to move not just your organization but also yourself individually; because I actually think as leaders we have the hardest work in changing the way that we work.

So, what do we mean by managing my outputs?

Let’s start at the beginning. A lot of the work that I do is with product teams, but if you’re not a product person in the room I really do believe this works broadly across the organization. In fact, I teach a couple of business classes to people that are not product folks and I use the exact same curriculum I use with product teams. So, when we talk about by managing by outputs this is easy to think about in the context of a product team. A lot of product teams are asked to deliver a fixed roadmap with some dates on it. So, deliver these specific features by this timeline. That’s a manager saying ‘I care about these outputs. Your responsibility is to deliver these outputs ‘. Now some of us are starting to think about what happens next. What if we produce all these outputs? Do we create any value for our business for our customers? And that’s what’s leading to this shift towards managing by outcomes. We’re not just saying build these features, or run these programs, or implement these initiatives. Instead we’re saying we really have a goal, an outcome we’re going for, and yes, we might run these programs or implement these features, but we’re not done until we’ve reached that goal. And so, the focus is more on the metric than on the activity. Now what I see in practice is a lot of teams say we get it. We want to have autonomous teams, we want to manage by outcomes, we want to take advantage of all the creativity in the room. But what happens in practice is it looks more like this: we go ahead and set OKRs, we give our teams a number., we tell them you have you’re empowered and you have autonomy go reach that number however you want but by the way do it by building feature A, B and C. Or do it by implementing program A, B and C.

Now I think most managers are doing this because we just don’t know a better way. For so long, business has been influenced by this top-down hierarchical command and control and we got to where we were because we mostly made pretty good decisions. And it’s really hard to let go of that and let other people make good decisions as well. I’ve thought a lot about what makes this hard at the individual level. And I came up with this sort of horrible vicious cycle where what happens is that as managers, we don’t trust that our teams can reach their outcomes. So, if we say we need you to increase engagement or we need you to reduce churn, we can’t just let go and say okay they’re going to go do that. Because most of our teams have been managed by outputs and they’ve never had to make those types of decisions. And because we don’t trust our teams, we then start to micromanage their outputs. We get to this screen where we give him outcomes and outputs, and then once we start micromanaging our teams as a result, they don’t really want to tell us what’s going on. Because when our teams tell us what’s going on, we start to micromanage. And so, it leads to even less trust because we have no visibility into what’s happening. Now, if we really want to manage by outcomes (and really give our empowered teams the ability to determine their outputs) and there’s a lot of reasons why we want to do this are our frontline teams are closest to the work, they’re closest to the customer, they’re seeing all day everyday what works what doesn’t work. We need to find a way to break this cycle. And there’s two ways that I want to talk about how we can break this.

Breaking the cycle

The first is we need to teach teams how to communicate 1) how to find the best path towards an outcome and how to communicate that progress. And, 2) as leaders we need to learn how to give feedback and give input without dictating outputs. Now I thought a lot about how to give this talk because that first part ‘How do we teach teams how to work this way’ is what I do for a living, and I could give a two day workshop on just that. And I have about 53 minutes left so we’re not going to do that! But the second part, what’s the role of the leader. I really think is the part that’s most important for those of us in the room, but I can’t really talk about the second part without talking a little bit about the first part. So, I’m going to walk through it a little bit. It’s going to you’re going to look at it and there’s cool visuals and you’re like ‘oh I want to learn more’, but that’s not really what we’re going to talk about today. I want to give you just enough so we can have that more important conversation. And then if you really want to learn more about that first part, I’m going to give you some resources and you can go ahead and do that in your own time.

So why don’t teams know how to communicate progress towards outcomes? We’ve taught them to communicate progress by talking about outputs. So, this visual for those for the product folks in the room to tell a board that I made it up and it’s a 12 month roadmap for Netflix that I totally made up. But this is how most teams communicate not just product teams. If you’re on a marketing team you’re probably talking to your manager about what marketing campaigns you’re running, and if you’re in H.R. you’re talking about employee engagement programs. You’re not talking about the outcomes themselves. Because this is how most teams communicate progress, we as managers give input on those outputs. So, it means 100% of the conversation is about outputs. But what we should be really caring about is what impact are those outputs having? What outcomes are we driving for our customers and for our business?

I like to use a really simple example of this. So, when our teams tell us about outputs we give them feedback on outputs and usually our feedback is not our expert manager feedback, it’s our preferences as an individual person. And that’s because our team has thought a lot about the outputs, but we’ve mostly thought about the outcomes. And so, when someone comes and says hey I want to create a red balloon that sounds pretty good but maybe we have a preference for blue. And so, we argue with our teams we say no you know what. Let’s not create a red balloon, let’s create a blue balloon. This sounds really silly, but I see it every week, and we all do this. We forget it’s not really just about our preferences, it’s about our customer; the need we’re trying to solve. And is there really a meaningful difference between a red balloon and a blue balloon? And if our team wants to go with the red balloon and we happen to prefer a blue balloon, but from a business and a customer standpoint there’s no meaningful difference, we should stay out of the way.

And we don’t do this. It’s really hard. It’s hard for us to know the difference between a preference and a true opinion based on evidence. And so, as a result we have this really common acronym that we’re all pretty familiar with in the product world. We like to say the HIPPO always wins. [Highest Paid Person’s Opinion] It doesn’t really matter how much research you do, how close you are to the customer, your CEO is going to helicopter in tell you to do something else.

Our job as leaders is to make sure we’re not the hippo. We may be the highest paid person but that shouldn’t mean our opinion doesn’t always win right. This is really what’s causing this cycle to happen as our teams don’t want to tell us what they’re doing because they don’t want their red balloon to turn into a blue balloon just because we have a personal preference. So, we need to do the work to understand what really matters, where should we be weighing in, and more importantly how should we be weighing in.

So, I want to talk a little bit about the types of problems we face in business to expose why some of this happens. So, there’s this concept from decision making problem solving research called ill-structured problems. You might have heard of them referred to as wicked problems, they’re problems where there’s no right or wrong answers compared to well-structured problems. Let’s start there. Well-structured problem. The key takeaway is that there’s rules that you can follow to solve the problem. So, an algebra problem is a well-structured problem. Economists like to think of the world as a series of well-structured problems. A lot of early business literature looked at business as well structural problems. If you just pick what category your product fits in – is the cash cow or – we have these really simple frameworks you just apply the rules, you’ll solve the problem. But we all know that that’s not really true right. All those frameworks take judgment, they take expertise, they take framing the problem and that’s because most of the problems we face in business are ill-structured.

An ill-structured problem contains elements that are unknown. They require that the problem solver define the criteria you’re going to use to solve the problem. And they require that we make lots of judgment calls along the way. We have to give structure to ill-structured problems before we can solve them. The other thing to highlight is that ill-structural problems have no right answers. It’s not black and white. It’s not that one answers right, and one answers wrong. Instead ill-structured problems only have better or worse answers. So, when we talk about a red balloon versus a blue balloon, they’re really both equally good answers. Maybe there’s a reason why a blue balloon is better than a red balloon. But more often than not when we give blue balloon type of feedback all we’re doing is we’ve framed the problem a little differently, and instead of talking about how we’re framing the problem, we’re micromanaging our teams by giving them feedback on their outputs.

So how we frame a problem is going to influence what types of solutions we can generate. We have almost 100 years of research on how designers solve problems, how we solve these wide open ill-structural problems and really what we’re seeing is exploring the problem space, how we frame the problem, is just as important as generating ideas. But in the business world what we’re seeing is that we’re just managing the solution space. And we’re losing a lot of the learning because every solution we entertain is going to help us better understand the problem. So, if we evaluate red balloons and blue balloons, we’re going to have a better understanding of what problem are we trying to solve. So, we manage it by outputs, what we’re telling our teams is that we have the right answer. We know exactly what we need to do to create value for our business and what we want our team to do is just do it. We told them to do. We’re assuming that the way that we frame the problem is the right way. And most of the time we don’t even bother telling our teams how we framed the problem. We just tell them the solutions.

When we manage by outcomes, we’re starting to recognize the problems we work on our complex they’re ill-structured. We need to take time to map out and understand the problems they face and that really we want our teams to do that work with us and to be a part of that so we get to leverage all of their expertise and knowledge and frontline experience with our customers so that we generate better solutions, we run better programs, we implement better initiatives. When we do this, we think about how do we get how do we help teams communicate how they’re framing the problem, how do we communicate how we’re framing the problem, we find ourselves in a situation where we’re having much better conversations. We’re not just talking about the outputs. We’re not just micromanaging work but instead we’re exploring the problem space together. We’re having much better conversations. So, I want to talk through what this looks like.

‘Opportunity Solution Tree’

This is a visual that I use. Inevitably whenever I talk about it some of the room loves it, some of the room has another visual that serves a similar purpose that they love. So, as I carry forward here I’m going to use this visual but I want you to know, the key here is to externalize your thinking. If you have another way of externalizing your thinking, you don’t need to use my tool, but we’re going to walk through how it works. This was designed for product teams, but I’ve since used it for all types of teams across the business. I called it an ‘Opportunity Solution Tree’ which is super awkward language. I’ll get into why I use super awkward language in a minute. If I were to rebrand it, I would call it an outcome map. Because it really is mapping all of our potential paths to our desired outcome. So, if as a business we’ve decided this is we need to reduce churn, we need to increase monthly recurring revenue, we need to increase engagement. It’s helping us, as a team, both as managers and as our teams visualize how we might get there. And it’s going to allow us to have better conversations and give better input than just output input.

So how does it work. It starts with defining a clear desired outcome. We talked about this a little bit yesterday in the OKR talk then it requires that we do the work to discover the opportunities that will drive that outcome. Now think about opportunity is a problem. So, I talk about exploring the problem space. The reason why I use the language opportunity – even though it’s super awkward – is because opportunity is broader than a problem. We often get really focused on solving a customer problem, but we also can delight our customers. We can replicate customer success. So, we want to have a little bit of this broader mindset than just fixing problems but also creating delight and replicating success. So, opportunity is just more inclusive language for customer needs, customer pain points, customer desires, customer wants. Now what’s really nice about this visual when we think about it this way is the blue box at the top is your business outcome. That’s what the business gets. The green boxes our customer needs. And if we only if we buy trying to figure out how to drive our outcome if we map out from the perspective of what do our customers need, we’re resolving that tension between what is the business need and what does the customer need. Now we’re looking at what customer needs will drive our business need. And then finally we have to discover the solutions that deliver on those opportunities.

So, I work as a product discovery coach, I teach product teams how to run this process. How do we start with an outcome? Discover the opportunities that will address that outcome and then discover the solutions that will deliver on those opportunities in a way that helps us find the best path to that business outcome. Now we don’t have a ton of time to go over this method, but I’m about to give you the highlights that we can then get into how does your role as a leader change in this type of world. So, it starts with we have to have a two way negotiation about an outcome. So, we got into this a little bit yesterday in the OKR talk. I really like to see a leader work with their team on setting an appropriate outcome.

The next thing that happens is the product team goes out and interviews customers. I say product team it could be any team. Literally, I’ve worked with marketing teams on this, HR teams, everybody across the company they go out they interview the people that would be impacted by their solutions. So, if you’re a product team at your end users or your customers if you’re an H.R. person working on employee engagement challenges it’s going to be your employees. Who are the constituents that are going to be impacted by whatever solution you’re building? You interview to discover what do they need? What are their pain points? What do they desire? What do they want?

We’re going to map out the opportunity space, then we’re going to pick an opportunity to focus on, then we’re going to generate multiple solutions that address the same opportunity. Why do we do this? Decision making research tells us we want to make compare and contrast decisions which of these solutions is going to best address the need. Most of us jump to the first solution we think of and we hope it solves the problem.

Finally we’re not going to just look at those solutions and be like ‘that one looks good’, we’re going to run experiments, we’re going to use rapid prototyping, we’re going to test our assumptions, we’re going to look at how do we evaluate these solutions to ensure that we’re pursuing the most valuable one. So, this is sort of the team process this is what the team does. I want to use this framework to talk about if we’re working this way we’re externalizing our thinking so that we’re being really explicit about how we’re framing the opportunities space, so that that sets up how we generate ideas, this gives us a really nice way to now talk about what’s our role as managers. How do we get out of managing outputs and back to managing outcomes? So, remember one of the challenges, one of the traps that we fall into as leaders, is we start with this red balloon blue balloon problem. This is a really silly example I tried to come up with the most harmless example, but now that it’s in your head you’re going to catch yourself doing it. Your team is going to come to you and say I think we should give this little kid a red balloon, and you’re going to go you know what I like balloons but let’s make it blue. And when that happens, I want you to catch yourself and say why am I doing that? Is blue genuinely better than red or do I just feel like to be the expert in the room, I have to have an opinion? That’s like the human messiness of this because we feel like we have to have an opinion. It’s funny I teach this and just yesterday I was sitting in the audience and I was having a problem with my admin, and I turned to my boyfriend who’s here and I said “I really just want her to do what I tell her to do.”

This is what we want as leaders. We just want our teams to do what we tell them to do. But is that really what we want. We want to take advantage of their expertise. We want to take advantage of their experience. We want to take advantage of their knowledge. We screw it up when we come in and say No, I think a blue balloon is better because to the kid the red balloon and the blue balloon are both awesome. There’s no meaningful difference and all we’re doing is we’re breaching trust with our teams, when we do this, we’re reinforcing this [HiPPO] stereotype and most of us are doing it every day and we don’t even realize it. And this is how I know.

So I was a startup CEO from 2009 to 2011, somebody else’s startup- I don’t recommend becoming the CEO of somebody else’s startup it’s not very fun – and I learned which I’m sure many of you have had this experience that I’ve been talking with people on my team and I was expressing an opinion. Like hey what do you think about this. And then I come back three days later, and they did that thing and I was like Whoa what did you do? They’re like well you said do this. And I thought we were just like riffing throwing around product ideas and then suddenly it’s real. So, part of this problem comes from the fact that if you’re the boss, it’s really easy for your team to confuse a preference or an opinion with do this. So, we need to be extra mindful of what we’re communicating and how. So, let’s talk about how we can fix this.

So, your first responsibility as a leader is to be really active in setting helping your team set good outcomes. I like to look at this as a two way communication part of it is because the leader has the best knowledge of the business priorities. So, the leader knows what the business needs. As executives we know our role is to think across the business, not what is my department need, what does the whole business need from my department. Most frontline employees don’t have that perspective. If they’re product people, they think about product. If they’re H.R. people, they think about H.R. What your team has is knowledge about what’s possible, by how much and how soon. So, if you go to your team and you say we’re having a problem with customers turning we need to reduce churn your team knows what that’s going to take. They’ve either tried it before; they have some ideas of what they could try. If they have a baseline, they probably can say reducing churn has been historically hard. We think we can only reduce it by a quarter of a percent in the next three months. Whereas the business leader is going to say we’ve got to reduce it by 10% next week. And then what we’re doing is we’re demoralizing our teams because we know that’s just not possible. So, this it’s really I see I see it go poorly when the leader just dictates the outcome. We demoralized our teams. I also see it where the team just picks an outcome and we’re all often missing that across the business perspective.

Framing the problem

If your team has done the work to visualize the opportunities space and I realize most of you have probably never seen this structure and they’re not actually using it but I’m going to give you some tips for how to think about this, even if they’re not doing this. But I think one thing the underlying principle of this visual is can you help your teams externalize how they’re framing the problem. So, remember how we frame the problem impacts the solutions we can generate. So maybe you frame the problem in a way the red balloon was the better solution and your team framed it in a way where the blue balloon was a better solution. But we battle about red versus blue, and we forget to expose that we’re framing the problem differently.

So, the first thing that we can do even when our teams come to us with their ideas and usually it looks like this even if they’re not externally visualizing it the conversation looks like this. They say ‘Boss, you told me I had to reduce churn. Here’s seven ideas we have.’ And when we just visualize our ideas, or we just talk about the ideas and we skip the opportunity space we’re not exposing how we’re framing the problem. And this is where managers just give it give feedback on the outputs because we don’t have more than that. So if this is the conversations you’re having with your teams the 100% of the conversation is about just the idea space, you want to start to introduce this concept of walk me through how you’re framing the problem now usually when teams start doing this it’s really shallow. So, they start with a really shallow understanding of the opportunity space.

Now a lot of these examples I’m using, they come from a Netflix example that I created. I’ve never worked at Netflix. I don’t know anybody at Netflix. Literally all of this was made up from my own experience with Netflix and talking to a couple other people. I use it because it’s relatable – you’re probably all familiar with Netflix. So, in this instance you can imagine maybe your team interviewed one Netflix customer and they heard a few problems they heard things like:

- I can’t find something to watch

- my battery on the plane runs out

- The video takes forever to buffer

So, this is a very deep understanding of Netflix’s opportunity space. Yes, we’re starting to get it. Customer problems but you probably all right now could think of twelve things about Netflix that annoy you. Right. So, if somebody comes to you and this is their knowledge about the customer we’ve got to send them back. Go talk to more customers, do a better job of framing the opportunity space.

This quote is it’s really awkward. So, if you’re trying to read it right now I’m going to walk you through it. John Dewey was a philosopher from around the beginning in the 1900s. He really focused on American civic life and how do we need to educate American citizens to support a democracy. We’ve clearly failed at that by the way. Here’s what John Dewey says this is it comes from his quote book ‘How we think’ it’s a really philosophical text but I think it’s the best text we have on what it means to be a good critical thinker. So, Dewey talks about

we need to maintain a state of doubt and carry on systematic and protracted inquiry. These are the essentials of thinking

I’m not going to lie, I had to google protracted. It means more comfortable more like longer than you feel comfortable. So what Dewey is advising us to do. Let’s say we someone says I have a blue balloon. That’s a solution. Dewey is saying let’s maintain a state of doubt. Let’s not jump to that first solution and let’s carry out a systematic and protracted inquiry. Let’s search for longer than it feels comfortable. Let’s do it in a systematic way, so we can guarantee that we’re making a good decision. This applies not just to the solution space but also the problem space. What customer needs are going to create the most value for our customer and for the business. And this I see really the cadence of business and we rarely give teams time to really do good critical thinking. But there are some easy shortcuts if we just start asking what else is missing? What else should we be considering? What other ideas do we have? What other customer needs can we address? Your blue balloon sounds like a great idea, what else have we considered? This is our putting Dewey’s critical thinking into practice.

Opportunities

The other thing I think our responsibility to ask as leaders is when our teams come to us and say we have this great idea, I think it’s going to solve this customer need. We need to ask how to do we know that customer need is real.

Do we just hear it from our loud sales rep who misunderstood the need? Have we heard it from one customer who has unique needs? Are we hearing it over and over and over again? And if we take the time to talk to those customers to observe those customers and to really understand this is a need, it’s real and this is how many of our customers is going to impact and therefore this is how much value it’s going to create if we address it. The other thing we can ask What opportunities are missing. And I actually think this is the root of the red balloon blue balloon problem.

So, here’s what happened someone comes to us with a solution we’re thinking about a different customer need. We framed a little different. So, the red balloon doesn’t feel like a good solution. But instead of saying ‘Oh I’m actually thinking about the problem a little differently from you’. Maybe we should align around that first. We just have the red balloon blue balloon argument. So, it’s really important that instead of just saying I don’t like your solution that we take one step back and say okay, we have to be curious. Tell me more about your solution: who is it for? What need is it addressing? How are you thinking about that need? How did you learn about that need? Then if I’m considering a different need, I can say okay I see that need, here’s what I’m hearing from customers. Here’s the needs that I’ve been learning about and now instead of having a red balloon blue balloon argument we’re having a really rich conversation about our customers and about what they need.

I apologize these are weird transitions.

I like to teach my teams to frame an opportunity as something a customer would say. Because when we frame our opportunities from the business point of view, we like to define opportunities as things like I really wish I spent more money on Amazon. Amazon wants me to spend more money on Amazon, but I don’t really want to spend more money on Amazon. So, if we frame our opportunities as something a constituent would say it’s a lot easier to catch that we’re not being customer centric. Now here’s the deal, I will spend more money on Amazon. If Amazon delivers it faster, if the product’s really good, if they have what I need, if I don’t have to get out of my pyjamas and go to the store – we learned about pyjama time. These are things that are real customer needs, if we addressed them, we’ll drive the business need of spend more money. But the reason why I like the opportunity solution to try visualizing this is the business gets one box. Spend more money all the green boxes are what’s keeping us customer centric. So really reframing customer needs in their own words is going to help be a really good litmus test for it’s really a customer need. Are we disguising a business need as a customer need?

The example in the slide is I want to pay for another subscription right which we all clearly think Disney’s coming out with one this week and somebody else, Apple is coming out with one this week. We clearly want to have a cable bill again. Whereas really what we want as customers is, we want compelling content. And if Netflix delivers really compelling content we’re going to subscribe. If we have kids you’re probably paying for Disney. So, the key is to really distinguish that and to make sure we’re staying customer centric. And I actually think this is the role of the manager because your teams are going to be so close to the product. It’s going to be really hard for them to think from the customer’s point of view. Everything in the opportunity space is going to show up as kind of a product feature/kind of a business need, because you’re a little further removed you can help them reframe you know what customers don’t want another subscription they want compelling content. How do we pull them back into the customer space?

This is related. Oftentimes I see people frame opportunities as features. A customer might say I want to fast forward through commercials. That’s not an opportunity, that’s a feature request. And one of the best ways to test whether an opportunity is really a customer need or if it’s a solution in disguise is there more than one way to solve this opportunity. What would we build to do this? Now I get that like there might be different technical architect implementations for fast forwarding commercials, but there’s one feature that’s going to solve this need. Which tells me it’s really an opportunity. So, we think about fast forwarding through commercials: What’s the real need? I don’t have other solutions but if I reframe it could be I don’t like commercials. Now there’s other solutions I can offer, I can give you a subscription where you can just get to skip the ads. I could give you more entertaining commercials. Now if the need is a little bit different. If it’s instead of I don’t like commercials, it’s I don’t want to be distracted by anything extra. Maybe you’re watching your favourite TV show on your commute to work and you really want to get two episodes in and when there’s commercials you can’t get the episodes in. Entertaining commercials doesn’t solve that need; skipping the commercials solves that need.

This sounds silly right this distinction but these this is what makes or breaks our products we miss understand the need we design a solution that addresses one need when our customer had a slight variation on the need. The conversations that get us out of the solution space or when we start to talk about how we are framing the opportunity. What are we hearing from customers and is it consistent?

The other thing I like about this tree structure is it’s not just about what opportunities are we capturing how we are grouping them and giving structure to the opportunity space. So, some of you might have opportunity backlogs that’s becoming a thing. And then your opportunity backlog is infinitely long, just like your user story backlog. So, then the question becomes how do we prioritize them. And you’ve probably read about these opportunity assessment templates. They’ve got dozens of questions. And if you have hundreds of opportunities you now could spend the rest of your life assessing opportunities. So, what I do is I have teams try to group related opportunities together and what that does is it allows us to use the tree structure to help us prioritize. Now in the grouping this is a really hard critical thinking task. It’s forcing you to ask what do we really know about these opportunities? What do we know about customer needs? Are they similar? Are they distinct? How what’s the right grouping? I just did this in a workshop in New York on Thursday and Friday and someone in their feedback wrote

thank you for making us feel the pain of critical thinking.

And that was the result of this exercise. It looks deceptively simply. It is it’s mentally challenging and it’s the type of mentally challenging work we should be doing, we often skip over.

Now the benefit of putting this work in is that now we can use the structure to help us prioritize. We don’t have to assess every opportunity we’ve heard. We can start with these top level branches and say which branch is most important. And then once we’ve picked one, we get to ignore the whole rest the tree and just prioritize its children. Now again if you’re not using this visual that’s not really the point. The point is this is to work with your teams to understand do they understand the problem space? Can they clearly and easily communicate the problem space and are they are they prioritizing it in a structured way? And can they justify the decisions that they made? So that’s our role as a leader in giving feedback on how we framed the problem.

We now want to look at how do we give feedback on the solutions they’re generating. How do we suggest a blue balloon without destroying the idea of a red balloon?

The first thing I like to look for is are they focused. So, if you took all the ideas in your backlog if you took all the programs you were running and you mapped them against customer needs. Odds are you would have one idea for each need that you’ve encountered. The problem with this is we’re not taking advantage of our creative minds. We’re jumping to the first solution. So, remember Dewey wants us to maintain a state of doubt, so we really want to do so we want to pick a target opportunity and generate more solutions than we’re comfortable doing. That’s systematic and protracted inquiry so you can see here we have about 20 ideas for the same need. Now when we start to evaluate which of these ideas might work best, we’re comparing and contrasting. Decision making research tells us comparing and contrasting leads to better decisions. So, you can ask your teams what else have you considered. It looks like we’re really working with a couple ideas should we generate more.

The next thing we need to do is we need to evaluate those ideas. We need to figure out how do we know what’s going to work. So, this is where we get into discovery methods like rapid prototyping, running product experiments. Most of this is going to be done by your team. So, what’s the role the leader? The first thing I look for is are they testing their assumptions. So more often than not a team has an idea for a program. They want to implement the whole program. A product team has an idea for a feature they’ve ever. Almost everybody at this point has learned to at least usability test things so they prototype the whole feature. Or worse they build the feature and AB test it. The problem with this is we just did a lot of work before we learned a single thing and for those of us that are doing this work that are actually testing what we’re building. We’re measuring the impact of what we’re building what we’re finding is that even the best teams have less than a 50 percent hit rate meaning most of the ideas we generate are not going to work. They’re not going to have the impact we expect. And our job is to learn that earlier not later, but we save our time and resources. So, part of this is how do you deconstruct an idea into its underlying assumptions. How do you break it down into iterative tests? So, you’re investing a little, you get positive feedback, you invest a little bit more, you get more feedback, you invest a little bit more. An easy question as a leader to ask your teams what are the things that need to be true for this idea to work. How do we test those things?

The next one I have a little bit of a silly example to explain do the ideas still address the target opportunity. I want you to imagine if the 1500s, you’re the captain of a ship sailing from Cambridge UK to Cambridge Massachusetts. And your goal is to cross the Atlantic safely, and you know there’s going to be a few needs along the way, you need to prevent scurvy in your crew, and you need to safely navigate the Atlantic. Obviously, we could build out a huge opportunity space here. And one day someone on your crew comes to you and says ‘captain the crew has scurvy. I think we should give them oranges; I hear that cures scurvy.’ Somebody else on your leadership team says ‘you know I don’t really like oranges. Let’s give them grapefruit.’ Grapefruit ‘s great, we’ll give them grapefruit. Then the guy responsible for cleaning the deck raises his hand and says ‘I don’t want to deal with grapefruit peels. Can we give them apples instead?’ That’s a reasonable request. Everybody says yeah let’s give them apples. What happened? We integrated our way to a solution that – apples are delicious. They’re totally valid fruit. They’re shiny – is a great idea. But they don’t solve the problem. This sounds silly. I just had a workshop on Thursday and Friday, I told them this idea everybody laughs I know what’s going through your head you would never do this. Then we worked on a case study and they started to evaluate their solutions and at least three of the eight teams said whoops our solution no longer addresses our target opportunity.

We do this all the time and it’s because each of those steps from oranges to grapefruit to apples was a logical step. There was a valid reason and each of those solutions is a good idea. They’re all good ideas. We could do all of them but only a couple of them solve the target opportunity. This is something, as leaders, I think we want to be on the lookout for as your teams start to explore solutions and especially as they evolve those solutions through experimenting and feedback and fixing problems that they encounter, constantly be asking is this still solving our target opportunity. You’re going to be surprised how many great ideas don’t drive your target opportunity and don’t drive your business outcome. We can save our teams a tonne of time.

This is what most trees end up looking like they get pretty big as you interview customers and you get a start to get a sense for what might drive our outcome. This is again is a made up Netflix example I don’t really have knowledge about Netflix’s world other than as a customer. What’s nice about this is if you add your teams externalizing their thinking in this way, you can see that we’re not just talking about a red balloon and a blue balloon. We have a lot of solutions we’re exploring and we’re not going to experiment with 20 ideas for the same opportunity. We’re going to whittle that set down. But if some of those don’t work out, we can go back to the larger set. So now when someone says we want to do a red balloon and you say a blue balloon it just gets added to the consideration set; you having an opinion about ideas for solutions is okay because there’s lots of ideas for solutions. You’re not telling your team what to build. You’re just throwing a suggestion out to be part of the consideration set. And more importantly if the reason why you want to do a balloon balloon is because you are framing the problem a little bit differently. It’s now clear you can look at the opportunity space and say you know what I would structure things a little bit differently. I would reframe this opportunity a little bit differently or I just talked to three customers and I’m hearing this need and I don’t see on your tree. Maybe that’s more important than what we’re focused on right now.

You know in business we ping pong all over the place right. We create a crisis every time we hear a customer need. And we jump from one week where the problem is this and this week’s the problem that; we drive our teams nuts. If we can visualize the opportunity space, when we have a crisis we can put it in that context and say okay something bad happened this week, how does it compare to all this other stuff we’re looking at right now. Do we need to interrupt our work or is this other stuff still more important? And because we’ve externalized our thinking. We have a much better conversation about it.

So, I know that I just threw a lot at you in particular if you’ve never been introduced to this visual or some of these discovery ideas. I did create this map it’s called the role of the leader. I know the text is too little. So, don’t try to read it right now it’s just a brief summary of what we talked about. Questions you can ask your teams. I will make it available to you in just a second. What we get when we do this when we externalize our thinking this way and as leaders we ask these probing questions rather than jumping in and saying I think we should do a blue balloon as we start to break this cycle. When we contribute to how the problem is being framed. We help generate solutions. We ask good questions about how we’re evaluating those solutions. We stop micromanaging, and then our teams have a way of communicating the progress they’re making towards their outcomes. And we break this cycle.

So there’s two maps; the first the one on the left is the one that your team follows – it’s what is your team doing to find the best path to a desired outcome – and the one on the right is for you as the leader. What are the questions you ask? To help understand what’s happening in this visual. Remember you don’t have to use. You have to train your teams on how to use this visual. You can’t if you want but the ideas here is how do you ask for what’s missing. How do you encourage your team to share how they’re framing the problem? You can grab both of these at producttalk.org/leadingdiscovery. And I’m very easy to find online. I blog at product talk dot org about continuous discovery. I’m really active on Twitter @ttorres. I love talking about this stuff. So, feel free to reach out and let’s talk about what’s hard what’s easy what’s working for you and keep the conversation going.

Q&A

Mark Littlewood: Thank you. We’ll take some questions quickly. You know the drill. Hands up. We’ll line the mics up. Let’s start at the back here.

Audience Member: I’m here. Thanks for the great talk. So, I like to think that I’m not only a leader but also an expert in some things. And don’t we all right. So, most of the time I don’t care about the colour of the balloon, sometimes I’m really really sure it’s going to be red. So, do you have any practical advice on how to tell when are you really contributing, you’re doing the right thing. But by offering your expert opinion or when you’re just being a HiPPO or should we you know if we are a leader should we just relinquish our role as an expert. And even though that could have been a factor that led you to be a leader in the first place.

Teresa Torres: Yeah, I don’t think you should relinquish your role as an expert by any means. I think here’s the thing we do want to contribute our knowledge and our expertise. We do want to help with problem framing. We even want to help with solutions. So, here’s what I see happen most often. A leader says we should do X. Well they’re not saying is I think we should do X because in the past I experienced problem A and solution X solved problem A. And the problem we’re looking at right now looks a lot like problem A.

If we did that now our teams can say okay, help me learn about what you experience problem a and your prior experience and let’s evaluate is this situation we’re facing right now, similar enough what are the ways in which is similar. What are the ways in which it’s different so that we’re doing two things? We’re taking advantage of your expertise but we’re still evaluating is this the right solution in this specific context. And we’re partnering with our teams on that. So, we’re not just going to them and saying I really need you to do solution X, remembering we have to include in our feedback why. How we’re framing the problem and see if it matches up with how they’re framing the problem.

Audience Member: By the way we’re from the same company but looking in different ways.

Mark Littlewood: Who’s the boss?!

Audience Member: So, it seems like your teams are the much awaited him the all are eager to give you all kinds of ideas. But what if your teams actually prefer that the product manager just tells them what to do and they take care of the technical stuff and they don’t want to get engaged. Do you have any tips how to get them more interested and like make them think about the problems they’re thinking from a broader perspective?

Teresa Torres: Yeah so, I’m going to ask the question. Let’s say you’re at a bar Friday night you’re having a drink with a friend. Your friend starts telling you about a problem he or she experienced. What’s going through your mind? What’s your first reaction?

How to solve it.

Human nature who has this the most in our organization?

Mark Littlewood: Men!

Teresa Torres: that’s a good answer! Engineers. Engineers we solve problems. That’s what we do for a living. So, if you’re finding in your organization that your engineers don’t want to be involved in the problem solving that is a cultural problem. Here’s what happens: we’ve dictated outputs for so long our engineers no longer think their opinion matters. And you’re going to have to rebuild that link. They’re human beings, human beings are problem solvers. It is human nature that we hear about a need, we want to solve it. So, there’s two ways to address this problem. One, invite your engineers to do discovery with you. So, they’re hearing first-hand from the customer what their needs are. Two, don’t just take in their engineer’s ideas and do something else. Invite your engineers to be full partners and idea generation in evaluating ideas. We need to reteach our engineers that not only do their ideas matter, because their technology expertise, they’re more likely to generate a better solution than anybody else in the building. If they get first-hand knowledge of a customers needs.

So it takes work but I really think that’s a symptom of a cultural challenge.

Mark Littlewood: All questions are on this side so they’re are obviously more intelligent. They’ve been listening better. That’s your chance to come back. Left hand side.

Audience Member: thank you for the great talk and maybe my question will reiterate a little bit the previous one; so you described the situation when you want to discuss something with your team. But then teams just start implementing it right away. So I encountered this situation many times and do have a framework how to solve it and how to make your team thinking about more ideas first – like slow them down. And don’t think about implementation but rather think about brainstorming and that sort of stuff; because what I found contributes to this kind of readiness to execute is um a fact that if they generate their own ideas they take more responsibilities and probably keep them from generating more ideas themselves. Any suggestions

Teresa Torres: Yeah. So I think a few things here when you generate a lot of ideas for the same need ideas become cheap right. So if you have one idea for one need and you come in your team has one idea and you come to them with another idea. It feels like you’re telling him what to do. If your team is considering 20 ideas and you just contribute to that pool of ideas and you really clearly communicate here’s an option to consider. And again this will take time to build that trust ideas become cheap and it’s not a red balloon versus a blue balloon. It’s the infinite universe of balloons and we just need to find out find a solution that will work right. This is the same with opportunities. Oftentimes we hear about a customer problem. It’s the last person we talk to on the phone. We helicopter in and we say we’ve got to solve this problem right now. We don’t bother to ask what are the other customer problems we’re addressing. So I see this a little bit. It’s analogous with when teams are new to running experiments. If you run one experiment a quarter a failed experiment is really costly, but if you run five experiments a week, a failed experiment is no big deal. So with ideas one of the things that we want to cultivate is how do we consider so many ideas that idea a suggestion isn’t is a weighty thing. And then I think as leaders it’s also really important that we talk about consideration sets. This is the set of opportunities we’re considering, this is the set of solutions we’re considering and making it really clear that we’re just adding to that consideration set. We’re not dictating this is the way we’re going to go

Audience Member: So it seems that sort of at the higher layers of a company over here over here at the higher layers of a couple manage by outcomes but if you imagine a growing company or even like kind of a boring old fashioned company a retail store or something there’s like layers of jobs and responsibilities like you just really want people just like performed the work that needs to be performed. Yeah. Your thoughts on like how to find that edge and how to help the right people move up over time?

Teresa Torres: This question is like personally palatable to me right now because I really want my assistant to just do what I told her to do. We had a pretty big error happened yesterday and it was client facing and I was sitting here in the audience and I just want to lose my sh*t. Excuse the language and I know better right. It was an honest mistake. It’s hard, I think this is the hardest thing we do as leaders, is that there’s always going to be like you don’t want your retail cashier to be reinventing your business. It’s not the right role for them but I do think every human being needs some autonomy in their job. This is part of that idea of mastery from Dan Pink’s book. I really think we drive autonomy mastery and – I forget the third one – but it’s this idea of like we all need to have some sphere of influence some sense of defining how we want to work. And I think the key is just to really get creative about for each level of employee what is that control you can give them.

I don’t have all the answers. I think one of the most challenging things I’ve done in my entire career is learning how to work with an admin, and I’m pretty sure I’m failing at it. And it’s because I can’t find this right balance of with the outcomes that gives her control that gets me the quality that I want. And I haven’t figured that out yet. But I know that it’s not me micromanaging what she does because I keep doing that and it doesn’t work right. I don’t I’d be happy to like during the break or whatever to brainstorm with you for different types of rules, but I definitely don’t have all the answers. What I do know is that when we give people autonomy and we find that scope and it works our employees surprise us every day we get way more from them. They come up with better ideas than we would have dictated.

Mark Littlewood: One last question.

Audience Member: Thanks for sharing that second level. Kind of about the framing part to make sure that everyone’s framing it correctly or at least on the same page. I guess my question is there a correct way to frame the problem because if you’re dealing with different subject matter experts, aren’t they all in some cases going to frame it from their own expertise? And once you realize we’re not confused you know this is I’m framing it. This is how you’re framing it. Is there a right way to frame the problem to get to the right outcome?

Teresa Torres: Yeah this is a fantastic question you get on a couple of things. So, you’ll remember when I talked about structural problems. They don’t have right answers. They only have better and worse ones and the visuals that I use there. There was no right. The idea of a right answer like algebra problem has a right answer. If you’re familiar with the Traveling Salesman Problem. There are better and worse solutions but there’s not one best optimized solution. It’s a complex challenging problem. This is the type of problems we’re facing in business so there isn’t I don’t want to think about it as like oh my framing is better than your framing the piece that you really touched on that I think is the thing we do want to capture. We’re all going to frame the challenge from our own unique knowledge and expertise, and if we want to come up with good solutions, we want to integrate all of that knowledge and expertise.

And this is where I think externalizing your thinking is a really powerful tool because it’s hard to align across different perspectives when we sit in a room and talk. You probably experience this every week and your leadership meetings. Right. Like it’s really hard to align when we’re just verbal. But as soon as you start making things tangible and concrete and you visualize them, you’ll be surprised at how many different perspectives you can quickly integrate. And that’s what leads to the I think the better problem framings. Thank you.

Find out more about BoS

Get details about our next conference, subscribe to our newsletter, and watch more of the great BoS Talks you hear so much about.

Teresa Torres

Teresa Torres is an internationally acclaimed author, speaker, and coach. She teaches a structured and sustainable approach to continuous discovery that helps product teams infuse their daily product decisions with customer input. She’s coached hundreds of teams at companies of all sizes, from early-stage start-ups to global enterprises, in a variety of industries. She has taught over 7,000 product people discovery skills through the Product Talk Academy.

Before coaching, Teresa led product and design teams at startup Internet companies, most recently, at AfterCollege. She was CEO of Affinity Circles, an online community provider for university alumni associations and a social recruiting service used by Fortune 500 companies. She’s also held product and design roles at Become.com and HighWire Press. She has a BS in Symbolic Systems from Stanford University and an MS in Learning and Organizational Change from Northwestern University.

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.