You’ve probably – no, definitely – heard of Eric Ries’ ‘Lean Startup’. Back in 2010, Eric joined us at BoS US to discuss some of the many lessons from his seminal book. In November 2017, Eric returned for a talk and Q&A centred around his newest book, ‘The Startup Way’ which explains how larger corporations can innovate and move quickly like a startup.

Lean Startup is not just for Startups. Through his experience working alongside some of the world’s biggest companies (GE, for example), Eric has seen how adapting Lean Startup can have a massive effect on innovation in a corporate setting.

Slides

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.

Transcript

I thought what we would do tonight is I will just share a few ideas from the book and give a bit of an overview. But I really am, you know, I think I’m in my third day now in London on book tour, I think this is my 15th event or something that I’ve had to do. So I’m a little bit tired of the sound of my own voice, if I’m totally honest. And I would love to have a conversation rather than just blab at you all day. So is that okay? Can we do that? Can we have some dialogue?

So I will share a few slides, share a few ideas, but really, at this stage, you know, as a startup movement, where we are I feel like people have gotten the basics. And we don’t need to be talking about like, what is a startup? And how do you create one? There’s so many more resources for entrepreneurs than there ever were even a few years ago. So, we’re drowning in knowledge, and gurus and experts, and whatever. And I feel like, we have an opportunity to have a much more real conversation. First of all, that gets beyond the surface level media reports about how easy and fun it is to be an entrepreneur. Hahaha. Right. And also to realize that we can make common cause with entrepreneurs that don’t fit the stereotype of what they’re supposed to look like. And I know we have tonight here entrepreneurs from corporate settings from nonprofits from governments. You know, one of the big ideas from the lean startup is that entrepreneurship is a management discipline, not that you eat ramen noodles, or whatever. So I’d like to kind of explore those connections tonight, if you’re with me, so are you with me? Thank you. Okay, good.

GE Healthcare Following The Startup Way.

And of course, although we’re at Businesses of Software, not specific to software. I thought I would start tell you a story of something that happened to me that if you told me it was going to happen to me, when I wrote The Lean Startup, I would have said: You’re crazy. You’re obviously not a time traveler, but a lunatic. And yet, this is a true story. So I was asked a few years ago to come meet with GE, you know, GE, the maker of all kinds of crazy stuff, from you know, engines and turbines, and healthcare and appliances and light bulbs and everything. And they said, would you come talk to us about Lean Startup. And I get that request from a lot of corporations. And I always say, Sure, happy to. But usually after I tell them what would be involved in them adopting the ideas, that’s the last I ever hear from them, which is great. It’s, it’s always fine by me, I don’t run a consulting company. I’m not trying to, you know, curry favor from big companies. So we did some stuff together. And they got excited about it. And unlike a lot of companies, they said: hey, we’d like you to come speak to the CEO and our top officers seriously about this, you know, in a more profound way. I’m not even sure what year it was. And I was in this tiered classroom full of super senior executives, the CEO and chairman. At that time, Jeff Immelt, was in the front row. And everybody in the room was one of his top 200 reports in the organization. So a very senior group.

I gave my little presentation about Lean Startup. I said, are there any questions? They were obviously not going to be any questions until everyone found out what the CEO thinks of this? So there’s no quit? Everyone’s like, well, ha, Jeff. He said something I’ll never forget. As long as I live, he said, I have a question. And he calls on one of his general managers by name. Your division only makes $500 million a year for GE. So why aren’t you already doing this? And then there were a lot of questions. So they really took it seriously in a way that I did not expect. And they had arranged for that same day that I was at Croton Ville, their legendary Leadership Development Center, famously parodied in 30 Rock quite accurately if anyone knows that episode, where they meet the six sigma and the whole thing. Whoever wrote that episode has been to a GE training at Croton Ville let me tell you.

And they said we were going to do a workshop to pilot see where the leads could really work in our company, Immelt said: you know, Chairman’s choice, I get to pick the project. That’s my prerogative, and I don’t want some dumb software thing. No offense, kid. We’re not gonna do some app, I want to see that lean startup can work just like you said in the book in many different industries. So I’d like to pick a diesel reciprocating platform called the series X. And of course, I had only one question, what is a diesel reciprocating platform and what does it do? I have no idea what we’re talking about. So this is a large piece of industrial equipment, a diesel engine that can be used for fracking stationary drilling which can be used in a locomotive. I would try to make a little mnemonic on it like okay on a boat by ground, on land in a on a plane in a train like Dr. Seuss style. Okay, got it. And we did this workshop.

Now I want you to visualize the scene of this workshop. Just bear with me a second. I’m again in another beautiful tiered seating business school style classroom. They have summoned to this workshop to Croton Ville, three people from Texas to who are on the series X team. Me up at the front. And then they have staffed the room with 25 corporate vice presidents, just to observe. This is not like a great setup for a workshop and these poor guys from Texas, can you imagine? Like the pressure that they’re under? On the one hand, they’re supposed to learn something from me. But if they learn something from this dumb software guy, what does that say about how good their plan was to begin with? So that’s not very attractive. But they don’t learn anything for me, that was that say about Jeff Immelt that he decided they should have this workshop. So it’s kind of an absolute lose-lose proposition plus, a lot of these vice presidents were like: Why do I have to go this thing? It’s like, because the corporate said, you have to have some skepticism in the room, perhaps.

And we had a conversation: what is the series X? And I was like, why don’t we start with what is this thing, and what is the currently approved business case for why we’re doing this. Now this product was going to cost – if memory serves – about $300 million for them to develop, so not a big program by GE standards, but for the rest of us, seems like that’s starting to be real money. They’re gonna spend five years on the research and development of it followed by a global launch, you know how this goes. And it’s gonna be using these five different use cases, simultaneously, they’re going to build out a whole new distribution network, go attack, some entrenched competitors sounded great.

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.

Predicting the Future.

The team then presented a graph, which I will never forget, so long as I live, it looked like this, I want you to visualize a bar chart, revenue forecast for series X engine for the next 30 years. Okay. And over here, there are five very notable blank spots, because the first five years of the forecast have no revenue, because obviously, we’re not going to have any customers while we’re doing our stealth r&d. And then it goes up to making hundreds of millions of dollars a year. And then the graph has a very distinctive shape you may be familiar with, where it starts to really and you guess I was looking up with these bars and the numbers are so astronomical, because think of the ROI, we have to justify this $300 million investment that got pretty great. I said: Okay, I may not know anything about diesel engines, but I’m very familiar with this graph. Because I mentioned, I’m from Silicon Valley, this is maybe our leading export, right up there with hype and buzzwords. So everyone in the room: hey, just do me a favor, everyone raise your hand, if you believe this forecast. And I’m not making this up. Every single person in the room raised their hand. And they were kind of miffed about it, too. They’re like: Listen, kid, I don’t think you understand. The brightest minds of the General Electric Corporation have vetted this financial forecast as the basis for our $300 million investments. So how dare you suggest?! I’m like: I’m so sorry, with all due respect, seriously? And I just picked apart random people and asked: who here believes that in the year 2027, you’re gonna make you know, $1.8 billion, or whatever it said, and I was like, exactly. And all these hands are like: of course, we don’t really know what’s going to happen in the future in the energy sector, where we can’t even forecast the price of natural gas, like more than six months, let alone 30 years from now, I really like when you put it that way. That’s lunacy. And listen, in normal life, if I was walking down the street and started telling people: I can predict the future with the power of my mind. It gets you in a lot of trouble in a lot of other contexts.

But in business, it’s fine. It’s fine. We can just do as much astrology as you want. And it’s totally fine. Like, why do we have that standard? Like, why do we pretend that we know what’s going to happen in the future? When we all know that we cannot do that? So we had a real interesting conversation in the room. Okay, what do we know? What do we believe? And what are the leap of faith assumptions, as we would say, in Lean Startup terms? And, you know, the conversation was going pretty well, we discovered that many of the assumptions that the team was focused on were purely technical in nature and was hard to look at the commercial assumptions. They were all buried in appendix B, footnote two. I remember one of them was like: because I had mentioned, we’re going to sell this to a new distribution network. And I was like, Excuse me? Do we have one of those already, you know, like, a holy grail from Monty Python? Like, he’s already got one? Like, do you have that already? Or not? And they’re like: No, we’re gonna build that from scratch. Do we know how to build such a thing from scratch? No, of course, we don’t. When are we going to start figuring out how to do the distribution network? Obviously, five years from now after the product is built. If customers don’t want to buy or the distributors hard, like, when would we want to find out that problem? Now, or five years from now, so we started having that conversation, it’s going pretty well.

And so we started talking about okay, what is the minimum viable product for the series X engine? And at first, I mean, this is like a running joke at GE for my many years of working there. Nobody wants to have a minimum viable engine. Right? Could these things explode? This is not software right? But things are totally okay. Right? Not not saying that we’re going to make it explode, but just is there any way we can make the engineering challenge of learning what customers want easier? Because why does this thing take five years? Because this one piece of equipment has to be used in the five totally different use cases. If you imagine how different fracking is from a freakin boat, a really different difficult challenge, right? So they’ve got to practically win a Nobel Prize in material science hit the efficiency target that’s in the requirements document, where did the requirements document come from? What’s really required? So it’s like, I understand that the laws of physics are required. But what are these? These are not requirements, these things are all optional. These are hypotheses about what customers might want.

So anyway, you guys are all familiar with this, because you came to this thing, because you presumably know what Lean startup is. And eventually, we said: Okay, well, what if we picked one of the five use cases to optimize for and then focus in on that. If you made the problem easier, we only had to do on land use cases, we could get it done in three years. And then eventually you’re willing to pick the stationary drilling use case where it doesn’t matter how much the thing weighs. We could get that done maybe in one year. And I’m like: Oh, this is getting fun. It’s like the engineering version of name that tune. And it’s like, well, I could get it done. So one of the engineers finally says: hey, you know, what, if you’re willing to pick this specific use case, and you didn’t care about how profitable the first individual engine was, we actually have an existing engine, it’s kind of similar. And we could just modify it to meet the performance characteristics of our requirements document. And I’m like: Ooh, how long would that take? And he’s like: you know, maybe six months. And now I’m like: let’s get good. I got a roomful of corporate vice presidents, anyone have a customer in this room that might like to buy this prototype that we’re going to have done in six months. And one of the VPS lo and behold, is in fact, every quarter, there’s one customer, that’s so annoying, they’re constantly demanding this exact product for me. And I’d like to make that. I’m like: Oh, we’re gonna make a deal. Right now. It’s going great. We’re gonna have a full order of magnitude reduction of cycle time, from five years, down to six months. And I’m going to be a hero. This thing’s gonna be great. And it was going well. It was one VP, who is just really not having a good time. Arms crossed the whole time. And finally I was like, I can’t take it anymore. I have to ask the question. What’s your question? He said, What? He did not say this. Exactly. But we’re in a church. What is the point? What is the point of selling only one engine? Like a minute ago, we were going to make $4 billion. And now what are we going to make like 25 cents? Of course, the engineer is like: oh, no, no. So we’re going to lose money. Because this thing, we have to sell it at the series X price point, but it cost too much money. He’s like, talking about why are we doing this? And I had to be like, Look, sir, you’re right. If this plan is going to work, and this forecast is correct, and we already know what we need to know, the learning is a waste of time. Experimentation is a waste of time. And he was like: Great, terrific, I’m out of here. And lucky for that.

And that would have definitely been my last day at GE for sure. Except several of his peers started to say: Well, hold on, hold on, hold on. Didn’t we just say a minute ago that we don’t know if the forecast is true, and hold on, what about these commercial assumptions. And they started to have a conversation amongst themselves about a different way forward with this product. That was the start of a program that eventually became called fast works at GE, that’s their version of Lean Startup course I write about it, and a bunch of other stories like it in the new book. We started with a diesel engine, and that is GE. So then we started doing like four projects at a time and then April. So then the next couple projects were like a neonatal incubator, a combined cycle, gas turbine power plant that cost $1 billion to make. Then we did a refrigerator. You know, we did a light bulb, we did deep sea drilling. I mean, just like Muppet Labs over there, we did air airplane engines, just every kind of thing you can make. We did wind turbines, and wind farms is a great renewable energy story in the book.

And eventually, to make a long story short, the company decided to commit to this way of working in to train all of their senior managers, and to do hundreds and hundreds of these projects. I routinely now meet with companies where there are more lean startup trained GE executives than there are employees in this company. And they’re like: oh, but it would be so hard to have to change the way that we work. I’m like: I used to buy that. But now I’m not so impressed. And like and I routinely meet people who say: well in my company, we have two or three or $3 billion company. I’m like: Yeah, but $3 billion would be an okay line of business for GE but not not that big. So not to be snobby about it. But what’s your excuse again? And that’s a bit of the theme of the new book, not to be snarky, but to say, there are people who have done this under very adverse circumstances in the US federal government and the army and the intelligence community.

We have some icy folks here tonight, who have done this in companies of every conceivable size from two founders in a garage, you know, every literally every order of magnitude to 20 200, 2,000 20,000 200,000. And everything in between. So lean startup has grown far beyond what we were talking about at Business of Software in 2010. And I think that I hope you will take inspiration from those stories, that there’s something interesting going on here. Yeah.

Lessons from The Lean Startup.

All right. So you may remember the five principles from Lean Startup, I have to refresh them myself sometimes. So let me just tell you the story again. But now through the lens of Lean Startup, like, first of all, why am I talking about entrepreneurship at GE, which hasn’t been a startup since Thomas Edison was alive? So it’s been a little while. Because entrepreneurs are everywhere. What makes you an entrepreneur is not that you eat ramen noodles or whatever, but that you’re trying to build something under conditions of extreme uncertainty. But because entrepreneurship is always management, it’s always institution building, it’s about coordinating the activities of people. Entrepreneurship is the kind of management, not a replacement for general management, but a new kind that is specific to situations like the series X engine where we don’t know what we don’t know.

But how do we hold those people accountable? How do we measure progress? If we don’t know what’s going to work or not, we can’t use any of our traditional metrics that we’re used to, we can’t look at ROI, we can’t look at ad revenue. Because we don’t have any, we can’t look at market share. Because we don’t have like all the key numbers are zero. And during the long flat part of the hockey stick, which you recall, ROI is negative by definition. So what are we supposed to do? So what we wind up doing in most situations is we build these fantasy plans. And then we get in trouble when the reality doesn’t live up to it. You ever tried to raise money from a VC? And they’re like, that’s a beautiful hockey stick shaped graph has happened to me once and they’re like, I’m so great. What are the units on this graph? Is this in 1000s? Or 10s? Of 1000s? Or whatever? You’re like, oh, no, sir. It’s an ones. But of course, the art of entrepreneurship and investing in in startups, is to be able to predict future progress from very scant leading indicators that are denominated in what we call validated or scientific learning. When we start to get more sophisticated about it, we can build a process of continuous innovation using the build measure, learn feedback loop.

I mentioned before that the series X engine, the key to the minimum viable product, the key to the whole thing was to get the learning time down from five years to six months, that full order of magnitude improvement. But to understand why that would be valuable, you have to understand that cycle time in a startup situation is defined by how fast you learn, not how fast just you build. Everyone’s with me so far. And then lastly, innovation accounting. This is the the part of Lean Startup, I don’t usually get fan mail about. I get a lot of comments about the stuff that fits nicely on a bumper sticker like pivot MVP, you can buy T shirts that say that stuff on them, you know, you can get out of the building Steve Blanks famous catchphrase T shirts. Now. I’m gonna let innovation accounting T shirts. And it’s a very boring part of the model. But there is math to this. This is not a manifesto. This is not like rah rah everyone be more innovative. Here’s my poster that says like, this is a management discipline just as rigorous and complex as traditional management. So I’m happy to win the q&a. I’m happy to talk about innovation accounting as much as you want, but you are not required to ask any questions about it.

But do not try this at home unless you master the accounting of: how do we show progress in financial terms, when all we have is learning. And you may have noticed, you can’t return learning to limited partners as returns, you cannot pay out learning as a dividend. You cannot put learning in your annual report and make people excited about it. Like nobody cares, except entrepreneurs about what we ourselves have learned. So we have to learn how to with a master the discipline of translating what’s been learned into financial terms. That all makes sense.

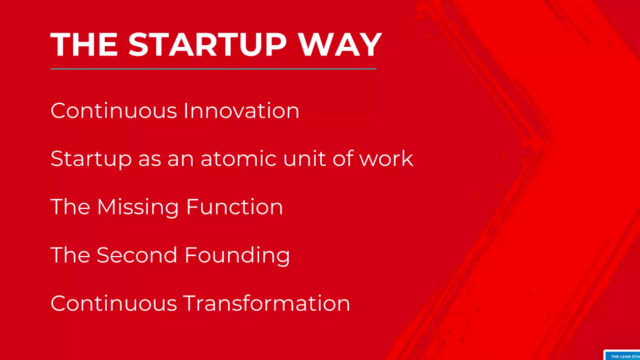

So the new book, let’s see if I get a slide up about it. It I really think of it as a continuation of the conversation we’ve been having in the lean startup movement, but trying to push it into these new frontiers and new domains. And it was really driven by two parallel things that were happening to me that I found a little bit strange in the last five years. One of which was I just told you about doing these programs, like GE is one of only several companies that I have done these fold top to bottom corporate transformation as we did it into it at Toyota. It was just a PNG the other day and like huge multinational iconic companies that if you told me years ago, I’m going to be working with them. I said: What? That’s crazy. And at the same time, many of the companies that were early adopters of Lean Startup are now pretty big companies themselves. And founders I don’t think actually prepare for this. We talk a lot about how most startups fail. But we forget that that means that some startups, God forbid, succeed.

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.

Scaling into Bureaucracy.

And most people became an entrepreneur because they hated the bureaucracy and politics and nonsense of being in a big company. I always ask them this question. Okay, hotshot. If you hate big companies so much why are you trying to create a new one? And we don’t think about that. We’re like: Well, my startup when it scales is not going to be like that. It’s not going to be bureaucratic. And you say: okay, great, but by what mechanism? What’s the plan for that to happen? And most are like: just cuz. I’m like: with the power of your mind, you’re going to make sure that like, what’s your plan? And so a lot of those folks, when I met them, they were just four or five founders in a garage. I would get a call a few years later now they have 100 500, 5,000 10,000 employees. I remember in those early conversations on lean startup, you were saying something about management management something something. But I wasn’t paying any attention because I was blinded by the light of minimum viable product. And that was cool stuff, management sounded pretty boring. But can we have that conversation now? And we were going to have these conversations about: what frustrates you, as a CEO of a unicorn startup, a very common complaint is I ask a team to go build me a new product, or I take us into a new market, and I say: I’ll give you full support, you know, right from my budget, I’ll give you all the air cover, you need go nuts. And then you know, they’re busy running their core business, and then they just go back to their main thing, but they see this project on the deck of approved projects with a little status indicator that says green.

So that gives them a lot of comfort. Okay, I may be busy with my core thing, but somebody’s thinking about the future making this thing, it’s gonna be awesome. Six months later, let me go check in and see: hey, how’s it going product manager of this project? And they’re like: it’s going right on track on budget, everything’s good. Terrific, like: so what did you learn from your last thing that you shipped? And they’re like: What do you mean, shipped? You said, everything was going fine. You’re making progress? Oh, yeah, we almost have the requirements document done. We’ve satisfied the scalability engineers that this thing is going to be able to be scalable to our full user base. So don’t worry about that boss, we’ve been working with the branding team to figure out how the launch is gonna go and make sure that doesn’t compete with the main brand. We’ve added a data, we’ve got this middle manager satisfied in that middle manager, we’re almost ready to begin implementation.

And I am thinking of a particular founder, who I basically got very upset with. And he was like: Don’t you understand that if we had followed those rules, when this company was founded, we wouldn’t be having this conversation today because the company would be dead. And the product manager said: No, I wasn’t there. How was I supposed to know that you have all these rules that I have to follow in the organization, like, get off my back man. And the founder was really shocked. He’s like: God, would I even want to work at this company? I mean, being the founder CEO is a pretty good gig. But would I want to be in it like what I want to work under those constraints? Of course not and like, could I even get hired at this company, our standards may be too high can I like, so we’ve like lost something of our innovative DNA. It’s a very common pattern, I hear it over and over again, when I meet with unicorn startups. What happened to that scrappy, innovative spirit?

And it’s really difficult. I remember coaching this entrepreneur in particular, like you got to see yourself, you’re not the entrepreneur in this company anymore. You actually have a lot of entrepreneurs that work for you. And what are you doing to train and support them? The way that your early stage investors trained and support you? It’s like, oh, that’s like, that sucks. I don’t want to be an investor. It’s like, a lot of things about entrepreneurship suck, right? So just add it to the list, man, what do you want? These people work for you, but you’re sending them into battle without the appropriate tools. And so it was weird. I wasn’t having those conversations. And then I’d be having a conversation with GE sometimes in the same day. It’s like a terrible wardrobe challenge. By the way, if you’re like, huge company in the morning, and then like scrappy startup in the afternoon, and, you know, how do you be credible to all those audiences?

This is my compromise, the best I can do. And this is the part that nobody believes, we were basically having the same conversation about team structure, about incentives, about systems about how do we support the entrepreneurs that work here, even though one company is 120 years old, and one company is five years old. And eventually, it dawned on me that the reason we’re having the same conversation is because these companies have been built to the same blueprint. That’s basically 100 years old, if you reincarnated the ghost of Alfred Sloan, who built General Motors in the 1920s. And you showed him the org chart for your favorite unicorn company. He’d be like: oh, yeah, good job. Like it would be completely comprehensible to him even though he’d be like, what does the product do? Again? A what? A computer like a soft, what? Like, he would have no idea anything about our modern economy. But our org chart would be like completely the same as what he’s used to.

Bureaucracy for the Modern Startup.

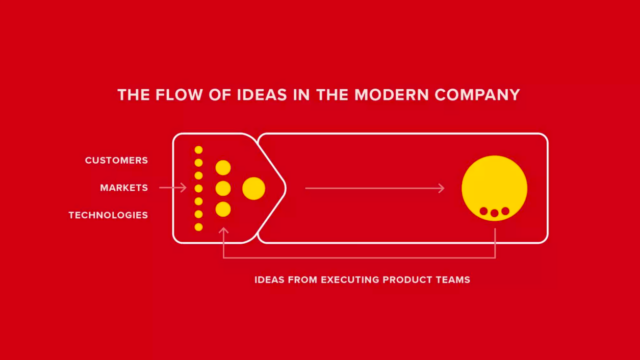

So I started to think about what is the right organizational structure and systems and incentives for what I started to call a modern company? What does it look like?

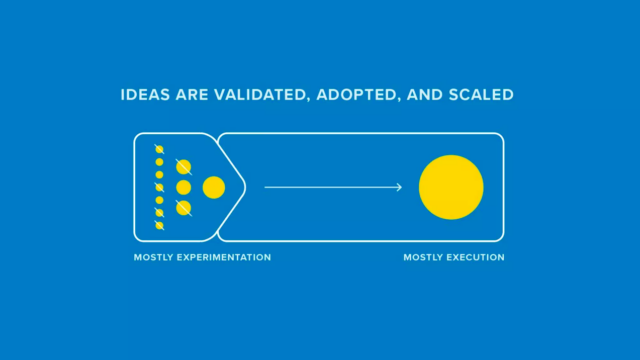

And the first is, we have to create the idea of the startup as an atomic unit of work. There are certain problem domains that we encounter more and more often in the 21st century where the startup is the right organizational tool to solve that problem. And to Mark’s point from before, sometimes a problem where you want to throw a startup at it happens to have venture style returns available and the right kind of business model and moats. And, you know, it’s comprehensible to investors. There’s all kinds of reasons why you can build a venture backed startup to pursue that opportunity. But there’s a much wider range of problems that are not venture bankable, but are still problems, still important. And we’re creating a dedicated cross functional autonomous team can tackle those problems in a way that most kind of committees and other kinds of team structures we use and most companies cannot. And I started to realize having watched companies struggle with dealing with their internal startups, that we in the startup movement have a series of totally universal beliefs that are just part of the water that we all swim in. And that to us are so obvious, we would never even think to write them down or say them out loud. For example, did you know that sometimes, small teams can be big teams? If that wasn’t true, there would be no startup opportunity at all. And yet, we all universally believe it. And yet when our companies grow up, what kind of teams do we make? We send big teams to solve big problems. Even though we knew at some level, we used to know how to do this properly. Every startup has a board, did you know that? And yet the teams that we create internally have to report progress in this bizarro matrix management nightmare.

I talked to most product managers, and I asked them, what percentage of your time do you spend defending your existing budget from other middle managers? They say at least 50% of my time. Can you imagine doing a startup with a 50% Productivity tax? Can you imagine if a VC after giving you a million dollars of investment called you up and said, we’re having a bad quarter here at the firm? I need 10% of the money back? No, that’s not how it works. That would kill any startup instantly, yet we run our retirement. In the book, I talked about how we use entitlement funding rather than metered funding, we forget the lessons that in this sort of movement we have so carefully pioneered, and we don’t apply them. So we need to create an organizational structure that can support entrepreneurs internally as well as externally with me so far.

Want more of these insightful talks?

At BoS we run events and publish highly-valued content for anyone building, running, or scaling a SaaS or software business.

Sign up for a weekly dose of latest actionable and useful content.

Unsubscribe any time. We will never sell your email address. It is yours.

Managing Entrepeneurs.

But now we have a problem. Did you notice that entrepreneurs are not the easiest people in the world to manage? Can you imagine you’re Steve Jobs’ boss? And he’s like, 20. I mean, right? Everyone says we’re a meritocracy. We believe good ideas can come from everywhere. And we want the next Mark Zuckerberg right here. They don’t mean one word of any of that. Like that would be so politically horrifying to them. So we have to figure out how do we manage entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial situations.

The Missing Function.

My simple idea, if you take nothing else away from the new book, I hope you take this away, I call it the missing function. If you look at our org chart, there’s just a missing function: who’s in charge? And most organizations are the following activities: Commercializing new products, bringing existing products to new markets, creating new IT systems, new HR systems, figuring out which corporate partnerships make sense, experimenting with new organizational forms. At best, those are individual responsibilities, part time of someone else in the organization somewhere, but they all have something in common. They’re all really entrepreneurship. And in most companies, when I say who’s in charge of innovation, the CEO will tell me everyone’s in charge of innovation, because we’re an innovative company. But can you imagine if we put up with that BS for marketing, we don’t need a VP of marketing or marketing function, everyone’s in charge of marketing, it’ll be fine. We don’t need a chief financial officer. Well, that seems like a lot of overhead finance is everybody’s responsibility. Or I have an idea, why don’t we create a finance lab. And we’ll have the finance people hanging out in the finance lab, and then we’ll just outsource finance to them. And the rest of us can just go about our business. Like, that is ridiculous. And yet, where’s entrepreneurship on the org chart?

So what are the problems when you don’t have a function, you have no career path, if you’re an entrepreneur in a unicorn startup or have like, we provide incredible support to founders of companies. But if you’re a regular entrepreneur, within a company, no support for you know, career path, your business card probably says Product Manager, God forbid, but so does the guy who’s building version 97 of the thing we’ve built before you’re in the same job, the same career evaluation matrix, that makes no sense. But also, we till we missing the kind of the vertical part of the Oracle, we’re also missing the horizontal things. Finance has a seat at the table whenever any company policy is decided. So if someone has an idea, like I have an idea, let’s like give our product away for free for no reason. Someone in finance can say, ah, that would be bad for our shareholders. And also we can’t afford it. And also, you’re stupid. What if someone else is saying: you know, I would like to adopt a policy designed to give us the absolute best absolute risk mitigation in legal or compliance so that we never have any liability. There’s nobody to say: Guys, the best way to achieve liability protection is to never do anything. So a process that is designed for maximum liability protection will be a process that prevents any team member experimenting anywhere who’s at the table to say that, if you’re lucky, maybe the CTO who also has side responsibility for innovation, we’ll remember it after they’re done their day job at 6pm. And they have little extra time. That’s absurd. Somebody should be working on this full time.

So we have a missing function in our org. We have to transform to support entrepreneurship as a corporate function, but now we have a new problem. Because: What’s that you say? We have to transform the entire org chart from an old thing to a new thing that sounds really hard? And it is. Transformation is extremely difficult. That’s true. Whether you’re transforming post product market fit, like think of a hard process. Going from a 100 person company to 1000 person company is excruciatingly difficult. The only thing worse is going to a zero person company, so we endure it.

Corporate Transformation: The Second Founding.

But any kind of corporate transformation is hard. I call it the second founding, it’s as hard as founding the company all over again. And I think the heroes that allow a company to grow up and become a sustainable enterprise should be revered every bit as much as the original founders for having accomplished the near impossible. But how many of those people can you name besides Sheryl Sandberg, right? So we have an industry problem with not recognizing the scope of that work. And lastly, just like lean startup, argue that innovation is not just you got lucky that one time, but it’s a process of continuous innovation, I want to play the same trick again, and get us to think about continuous transformation, because can I just level with you for one second? Come on, what are the odds that I have written the last management book that we’re gonna need? Like he says, drive you crazy about business books, like it drives me crazy, like, if you just do why my one thing, everything will be fine forever, and you’ll never need to read any more business books ever again, call my publisher, hang it up, guys. It’s over.

Every bit of the argument about how crazy the 21st century is going to be in the product domain applies here, too. So if we’re going to build up the capability to endure this kind of transformation and get good at it, why do we throw all that away? In the same realization? Like we eventually figured out that when a founder drives a company up to scale, why don’t we fire them and get them out of the building, when we need that experience? It’s a valuable resource, it is a corporate capability. And just like we’re always experimenting with new products, we should be experimenting with new organizational forms. So this is not the last management system you will ever need. But rather, the first management system that contains within it, the seeds of its own evolution. Makes sense so far.

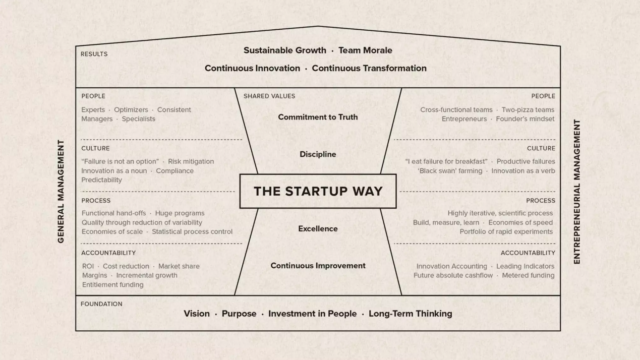

Okay, one last thing. Everyone know the famous Toyota house diagram, if you ever read The Toyota Way or any of the lean manufacturing books, I wanted to do that same kind of a diagram for the kind of overall theory. So I want you to at least see the shape of it. So you can flip to that page of the book or you can go on the website, you can download a poster size, like illustrated version of this, so you can really study it if you like it. Or you could just use it as a doormat or something. In any event, over here, we have the domain of general management. And over here we have the domain of entrepreneur management. And you may remember a diagram from lean startup called the startup way, that says that the causal connection between the parts of an organization go like this accountability, process, culture, people in that order, if we try to adopt lean startup or any other process method, but we use the same old accountability tools that will not work, teams that are held accountable to the right kind of metrics have the opportunity to self organize around new tools, like minimum viable product, or pivots or whatever you would like those teams become the seed and opportunity to incubate a new culture that will allow us to attract and retain the best people, the most entrepreneurial and creative people.

So that’s not a replacement for general management, we’re going to do both of these pillars in every organization for the foreseeable future. And I tell a story in the book about one of the people I met a Six Sigma Black Belt leader, who I was trying to explain lean startup to, and it was going fine, except that I was heavily distracted, and could not focus on what he was saying, because he had a mug on his desk. And the mug said in big black letters, failure is not an option. And I couldn’t stop looking at it. And I was just like, what does it say about this person that they believe that that is a true statement, and also something to brag about and put on a mug. They must live in a world where every time you fail, it’s because you had insufficient preparation and diligent work. And I was like, so culture failure is not an option over here. I was like, Well, gosh, if I was, if I made a mug of the entrepreneurship mug, what would it say? I eat failure for breakfast. Okay, if I get to lunch, and I’ve only failed five times, that is a very good day on average. And it’s not because I’m not diligent, and I don’t prepare, it’s because I’m in a domain, a different problem domain where the uncertainty is too high. To prevent failure, we just have to roll with it and try to learn as much as we can from we call productive failures. Hi, everybody. We’re all productive failures now. Okay, that’s the good thing. But that’s so it’s just, it’s not that he’s bad. And I’m good. It’s that we work into different domains of the organization. And by being able to see the difference for those two cultures. It allows them to peacefully coexist and even to harmonize to achieve these shared outcomes, including things like the superior morale that comes from the scarcity mindset of a startup team, the, you know, the acceleration of business results that these tools can allow, and they’re built on a shared foundation of vision, purpose and investment in people and of course, long term thinking.

So I told you I was part of the sound of my own voice. So that’s it. Let me pause here. And, you know, if you really want to look at more diagrams, they’re in the book so you can look them up. Or I’m happy to answer questions or whatever like, but I really as much as possible love to have a conversation. Thank you all so much for coming out tonight. And I hope you really do enjoy the new book. Thanks for coming. And thank you, Mark. Thank you. Thank you.

Eric Ries

Founder & CEO, Long Term Stock Exchange

Eric is a computer scientist, CTO, entrepreneur and author of The Lean Startup. The Lean Startup methodology has been adopted by countless startups and companies across the world. The term, ‘pivot’, a key concept, entered mainstream culture.

The Lean Startup was also the inspiration behind LTSE.

Eric founded the LTSE in 2012 in order to offer a route to capital for companies that prioritize the well-being of customers, employees and others stakeholders that encourage and sustain innovation.

He spoke at Business of Software Conference before he’d even written his first book.

Next Events

23-25 September – 🇺🇸 Raleigh NC

BoS USA returns to Raleigh NC

Learn how great SaaS & software companies are run

We produce exceptional conferences & content that will help you build better products & companies.

Join our friendly list for event updates, ideas & inspiration.